Denouement

When I set out on this journey in May, I thought it would be easy: recite the anecdotes, give a little context, throw in some ambiance… As I got deeper into the research, though, I discovered more than I bargained for. There’s a lot of history in those six months of 1918, and in that short time, there are only so many occasions that certain of the anecdotes could have taken place. That I could narrow down the times and places of most of the stories to within a few likely days of Ben Potts’s journey has been a tremendous reward.

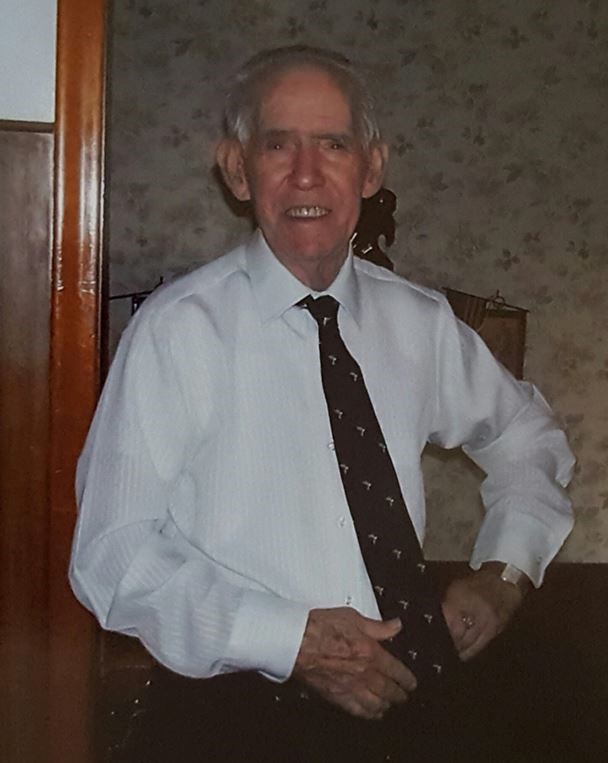

I wish I could sit down with Grandpa and show him my notes. With what I’ve learned, I’m sure I could jog his memory and get a few more stories out of him. You’d all be invited, of course. Granny would make another pitcher of iced tea.

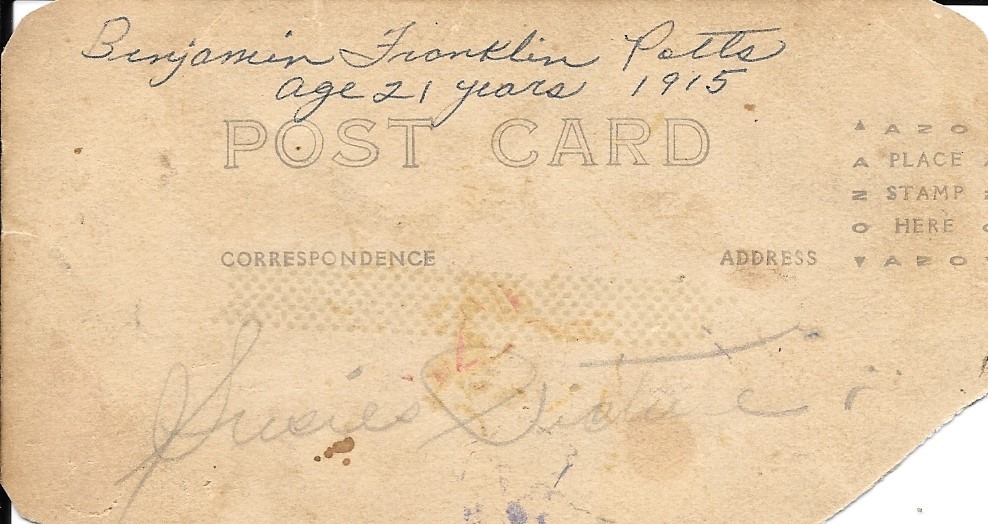

My great grandfather, like many veterans, didn’t talk much about his wartime experience. His family has only his discharge paper and a few anecdotes.

One hundred years later, I’ve discovered a few documents that bear his name. From draft registration to discharge, I’m following the paper trail of B. F. Potts’s journey to the battlefields of the Great War in France and back home again.

Previous articles:

“Well, Daddy, what did you think about France?”

“It’s a very muddy place.”

Benjamin Franklin Potts Registers for the Draft

As the Great War thundered across the fields of northern France, ten million American men, ages 21 to 30, signed their names to register to be drafted into military service.

Military Induction and Entrainment

“I, Benjamin Franklin Potts, do solemnly swear to bear true allegiance to the United States of America, and to serve them honestly and faithfully, against all their enemies or opposers whatsoever…”

“If it moves, salute it. If it doesn’t move, paint it!”

Embarkation, the Tunisian, and the Bridge of Ships

In his first ocean voyage, B. F. Potts crossed the submarine invested waters of the North Atlantic in a convoy of steamers escorted by a warship.

Enterprise, Tennessee: The Town That Died

Grandpa owned matched pairs of horses. Him and the boys [Ben and his brothers] cut and snaked logs out of the wood to the roads. He got a dollar a day plus fifty cents for the horses.

Rendezvous with the 35th Infantry Division

“Some of the guys disobeyed orders, went into the town, broke into a bakery, and stole all the bread and baked goods…”

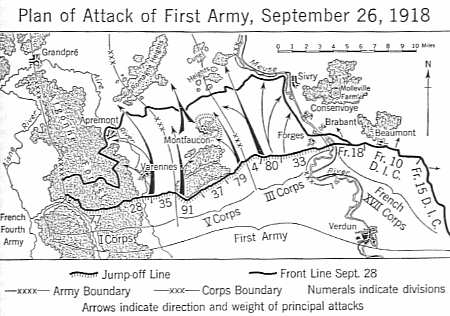

The battle of Saint-Mihiel (September 12-15) would be Pershing’s first operation as army commander. He assigned the 35th to the strategic reserve, whose purpose is to replace a weakened unit or to fill any gap in the line created by the enemy.

“Private Potts, how tall are you?”

The soldier, looking into a button of the captain’s coat, says, “Five foot three, sir.” The wide brim raises.

On the front now, the 35th was in range of artillery fire, and enemy planes made nighttime bombing raids over the countryside.

Planning the Meuse-Argonne Offensive

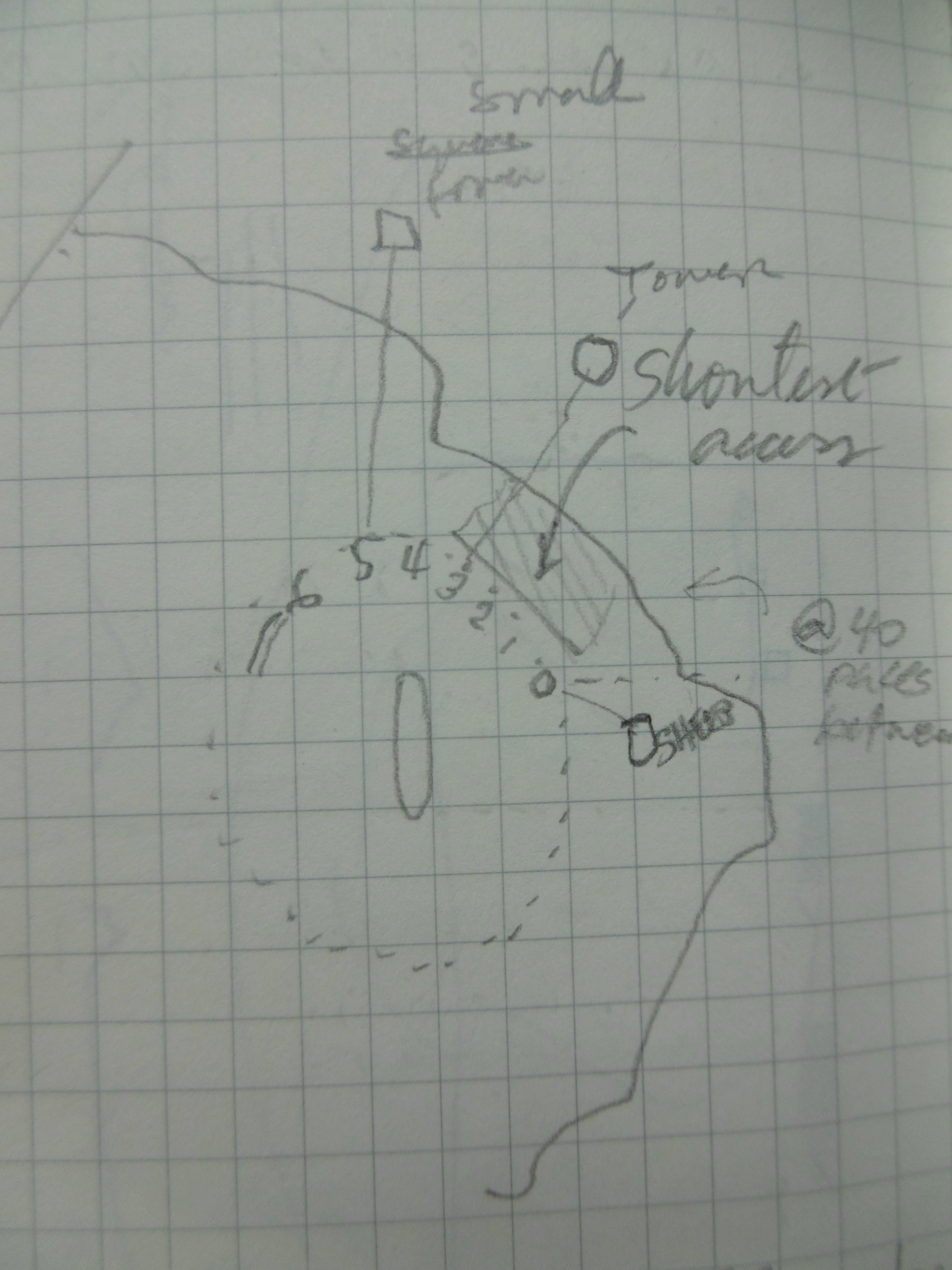

On the left, the 137th would take the “V of Vauquois,” a formidable network of trenches, zig-zagging from the hill’s west flank to the village of Boureuilles, a mile away.

The gun jumps, the earth shudders, a shock wave shatters the air and accompanies a roar that bursts between the ears. Powder fumes permeate the air. Explosions count seconds across unending darkness.

…up until 7:40 a.m. when the rolling barrage ceased, we can follow Private Potts’s movement across the battlefield.

Scrawling in a notepad, the commander tears the sheet, folds it, and thrusts it into the runner’s hands.

“Potts, take this message to brigade. Tell them we need artillery now. Go!”

“Let him lie in an artillery shower all night, if you must. But do not disturb a soldier’s sleep, sir, with your orders that change from one minute to the next!”

By morning’s end, the intermingled 137th and 139th regiments gained 500 meters and dug in before Montrebeau Wood. Through the woods and German machine-gun nests and sniper fire, the men fought in the afternoon.

“When I asked him [Grandpa Ben] if he killed anyone, this is what he told me…”

As the men would destroy one machine-gun nest, other enemy gun crews were setting up on both sides of their skirmish line.

Clyde Brake Boards the Leviathan

In the morning of April 6, 1917, the day the US declared war on the German Empire, American army troops seized the Vaterlund at its mooring in the Hoboken harbor.

When the digging was done, they dropped into the trenches, exchanged shovels for rifles, and pointed them north.

At 3 a.m., October 1, the 35th Infantry was the fourth of Pershing’s nine front-line divisions to be relieved from the front.

“…he was near the spot where a shell landed and was buried under dirt.”

“Ben had been told that his brother, Roy, had died. Then he ran into someone who said, I just saw your brother over at so-and-so medical. So he went to get a pass…”

Upcoming dates:

October 26—An Unremarkable Day

November 11—The Armistice

April 23—Return Aboard the Manchuria

May 13—Homecoming

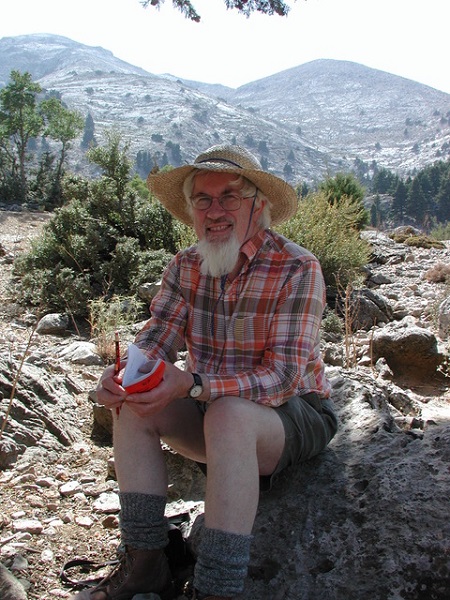

Oliver Rackham, 1939-2015

Oliver Rackham, 1939-2015 Zelkova abelicea, circa 1300-

Zelkova abelicea, circa 1300-