Mouchel and Langlois, Cherbourg Tutors

“You don’t mean to tell me that this young man made those drawings by himself!” said Mouchel.

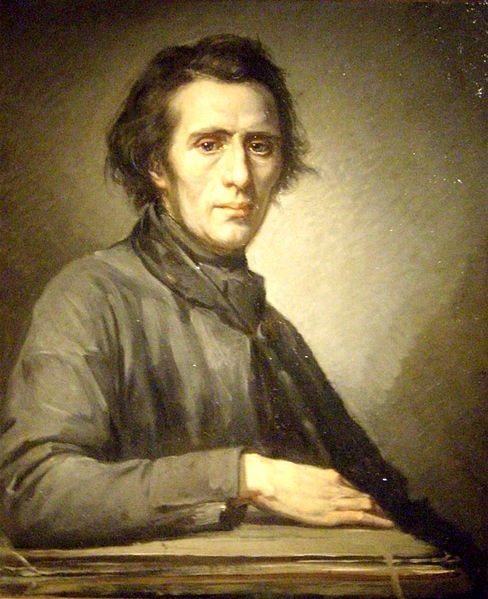

The elder Millet defended his affirmation, saying he watched his son draw them. He had brought Jean-François to see this Cherbourg artist who was also a tutor. They showed him two drawings the boy had made, hoping Mouchel would take him on as pupil.

The younger Millet insisted on his sole authorship, and Mouchel was eventually convinced.

“Well, then,” he said to the father, “all I can say is, you will be damned for having kept him so long at the plough, for your boy has the making of a great painter in him.” (Cartwright 32)

Thus, Jean-François Millet went to study painting in Cherbourg. Of his first tutors, history records little. Alfred Sensier devotes a few pages to these two characters in his Millet biography. Those pages, including footnotes added by the editor Paul Mantz, may well have saved the names of Bon Dumoucel, called “Mouchel,” and Lucien-Théophile Langlois from history’s oubliette. Though my research is far from exhaustive, Sensier’s work is the source of every other reference to them I’ve so far found.

Sensier describes Mouchel as a curious character. A self-taught artist, he followed the neoclassical School of Jacques-Louis David. He began many large canvases but didn’t always finish them. On request of local clergy, he painted alter.jpgeces, which he then donated to the church.

Mouchel taught at his home-studio in a small valley on the edge of town, where he lived with his wife. He worked a garden beside a mill and had a pet pig whose language he understood and could speak. Sensier, less bold, writes, “pretended to understand” (emphasis mine).

As Millet’s tutor, he recognized genius in the young man and gave him free rein: “Draw what you like; choose anything of mine that you like to copy; follow your own inclination, and above all go to the Museum.” (Cartwright 33)

It was at the Thomas Henry Museum where a messenger found Jean-François to inform him of his father’s illness.

Months later, Millet returned to Cherbourg under another tutor. Théophile Langlois de Chévreville was a trained artist, student of Antoine-Jean Gros, also neoclassical. During his own studies, Langlois had traveled to Greece and Italy, a fact he made sure everyone knew. He was considered as Cherbourg’s best painter. Some years later, he would become a drawing professor at the town college.

Like Mouchel, seeing that he didn’t have much to teach the young man, Langlois gave his student much the same treatment as his predecessor. “Go to the Museum,” was a common refrain.

After less than a year, Langlois penned a letter to the Cherbourg town council to make Millet’s case. In the letter, he suggested that the town provide the promising artist with a scholarship to study in Paris. So confident was he in Millet’s talent, he dared to predict the future:

“Allow me, gentlemen, for once, to lift the veil of the future, and to promise you a place in the memory of mankind, if you help in this manner to endow our country with another great man.”

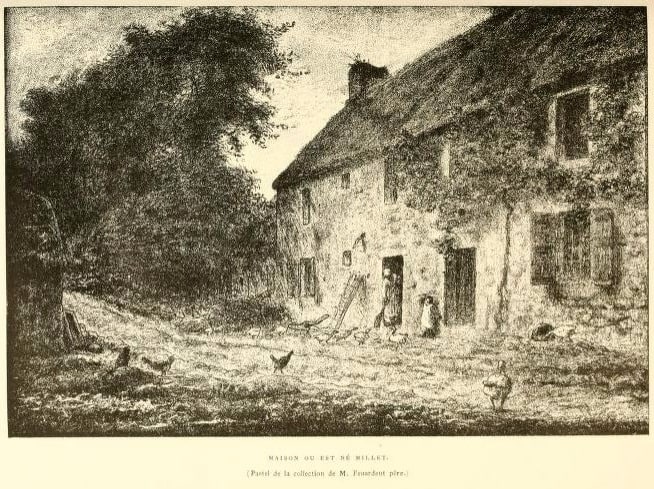

In January of 1837 with a Cherbourg scholarship of 600 francs, Jean-François Millet bid farewell to his mother and grandmother at Gruchy and rode by carriage to Paris.

Quoted dialog from Jean-François Millet, His Life and Letters by Julia Cartwright (London: Swan Sonnenshein & Co., 1896).

Biographical information from La vie et l’oeuvre de Jean-François Millet by Alfred Sensier (Paris: A. Quantin, 1881).

On the Normandy coast near Gruchy wind and rain are not uncommon in any season; late July 2016, this was the day’s best weather

On the Normandy coast near Gruchy wind and rain are not uncommon in any season; late July 2016, this was the day’s best weather