The wood is primeval. Prehistoric relics indicate human presence in the area of the Compiègne Forest since time immemorial. Beech, oak, and hornbeam trees sheltered game in Roman times. Since then, the forest has been the hunting ground of kings and emperors, the playground of princes and princesses, as well as a battleground. Julius Caesar fought the Gauls beneath its canopy. Merovingian kingdoms Austrasia and Neustria exchanged blows between its stout trunks.

During three days in November 1918, the ancient forest served as secret meeting place for negotiators of two warring sides seeking peace. A delegation for the German Empire arrived November 8. The Allied delegation was led by the supreme commander, French General Ferdinand Foch.

Negotiations took place in a railcar, arranged for the purpose, positioned in a secluded glade near the French village of Rethondes, a hundred kilometers (60 miles) north of Paris. General Foch chose the site to keep journalists at bay and to avoid distractions.

Playing from a position of strength, Foch presented himself to members of the German delegation on the morning of the 8th, gave them a document listing the terms of a ceasefire, and told them they had 72 hours to sign it. He would return only once more.

The terms were strict: withdrawal of all German forces back to pre-war borders, plus evacuation of the Rhine Valley on Germany’s western flank; surrender of all military equipment (artillery, machine guns, ships, aircraft), including trains and trucks; renunciation of two earlier treaties with Russia and Romania, and restoration of booty taken from Russia, Romania, and Belgium. All infrastructure of evacuated territory was to remain intact, and the naval blockade of Germany would continue. The terms included no concessions by the Allies.

Hopeless as was their military position and with worsening social conditions at home, the Germans had no choice but to agree to the terms.

Between 5:12 and 5:20 a.m. on November 11, four members of the German delegation and a leading Allied representative signed the armistice. General Foch entered, examined the signatures, and, after adding his own mark to the document, departed for Paris. According to the conditions of the ceasefire, fighting would end within six hours.

In the Sommedieue sector, Carl E. Haterius, 137th Regiment Band, recorded the scene in his journal. Private Benjamin Franklin Potts, Company M, must have been within earshot. Through the journalist’s words, we may relive the moment with our ancestor:

“At the eleventh hour on the eleventh day of the eleventh month, hostilities came to an end from Switzerland to the sea. Early that morning from the wireless station on the Eiffel Tower in Paris, there had gone forth through the air to the wondering, half-incredulous line the Americans held from near Sedan to the Moselle, the order from Marshal Foch to cease fire on the stroke of eleven.

“On the stroke of eleven the cannon stopped, the rifles dropped from the shoulders, the machine guns grew still. There followed then a strange, unbelievable silence, as though the world had died. It lasted but a moment, lasted for the space that the breath is held. Then came such an uproar of relief and jubilance, such a tooting of horns, shrieking of whistles, such an overture from the bands and trains and church bells, such a shouting of voices as the earth is not likely to hear again in our day and generation. When night fell on the battlefield, the clamor of the celebration waxed rather than waned. Darkness? There was none. Rockets and a ceaseless fountain of star-shells made the lines a streak of glorious brilliance across the face of startled France, while, by the light of flares, the Front and all its dancing, boasting, singing peoples was as clearly visible as though the sun sat high in the heavens.” (Haterius 181-182)

The ceasefire was prolonged three times before the final agreement, which included a clause that placed the blame for the war and all its ramifications on Germany. The intent was to prepare a legal case for war reparations, but when Germany signed the treaty on June 22, 1919, it humiliated the German people as well. Ratified on June 28, the Treaty of Versailles would bring the first of the world’s two great wars to an end.

After a time in a museum at Les Invalides in Paris, the railcar in which the signing took place was moved back to the site in the Compiègne Forest, which became an historic monument and place of pilgrimage for tourists and survivors of veterans and war dead.

There, in the same secluded glade in the primeval forest, in the same railcar originally chosen by General Foch, another armistice would be signed twenty-two years after. June 22, 1940, Adolf Hitler chose the site for the formal surrender of France to Nazi Germany.

Reminiscences of the 137th U. S. Infantry by Carl E. Haterius, Topeka, Kansas: Crane & Company, 1919

Reminiscences of the 137th U. S. Infantry by Carl E. Haterius, Topeka, Kansas: Crane & Company, 1919

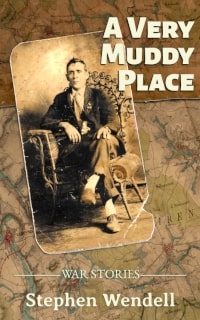

A Very Muddy Place

WAR STORIES

An intimate account of a soldier’s experience in World War I, A Very Muddy Place takes us on a journey from a young man’s rural American hometown onto one of the great battlefields of France. We follow Private B. F. Potts with the 137th US Infantry Regiment through the first days of the Meuse-Argonne Offensive. We discover a personal story—touching, emotional, unforgettable.

In 1918, twenty-three-year-old Bennie Potts was drafted into the US Army to fight in the World War. He served with the American Expeditionary Force in France. At home after the war, he married and raised a family, and the war for his children and grandchildren became the anecdotes he told them.

A century later, a great grandson brings together his ancestor’s war stories and the historical record to follow Private Benjamin Franklin Potts from Tennessee to the Great War in France and back home again.

Available in hardcover, paperback, and e-book.

More about A Very Muddy Place…

Disclosure: This page and linked pages contain affiliate links to Bookshop, Amazon, Apple, Barnes & Noble, and Kobo. As an affiliate of those retailers, Stephen earns a commission when you click through and make a purchase. Thank you for your support.