Secret Hideout

Sometimes when I need less distraction than I get at the field office, I have a desk at an undisclosed location. The building is in this photograph. I can’t say more because, you know… secret!

Sometimes when I need less distraction than I get at the field office, I have a desk at an undisclosed location. The building is in this photograph. I can’t say more because, you know… secret!

I met Tom at a café I call the field office. Tom teaches history of religion to high school sophomores in Arizona. He comes to Paris every year to do research at the Bibliotèque François Mitterrand.

I met Tom at a café I call the field office. Tom teaches history of religion to high school sophomores in Arizona. He comes to Paris every year to do research at the Bibliotèque François Mitterrand.

Tom said, “I work six floors under ground on the garden level.”

I said, “I gotta see that,” and we made plans to meet the next day.

Tom wasn’t kidding. The Rez de Jardin is the research floor at the BnF. This photo was taken from the entrance level overlooking the garden, which is rather more like a forest.

Jardin at the Bibliotèque François Mitterrand

Jardin at the Bibliotèque François Mitterrand

Below, the garden is surrounded by room after room of books and work spaces. Labeled by letters K through Y, the rooms are classed by subject: philosophy, history, science and technology, economics, politics, art and literature, and the rare book reserve.

Tom gave me a tour. We got as far as the rare book reserve…

Tom gave me a tour. We got as far as the rare book reserve…

The rare books are kept in room Y. To get to room Y, there’s a door in the back of room T. The door leads to a narrow elevator that goes up two floors into a low-ceiling space, filled with chest-high book cases, quiet, and dimly lit. A friendly, young man took our accreditation cards and let us browse. I was hoping he’d give us white cotton gloves.

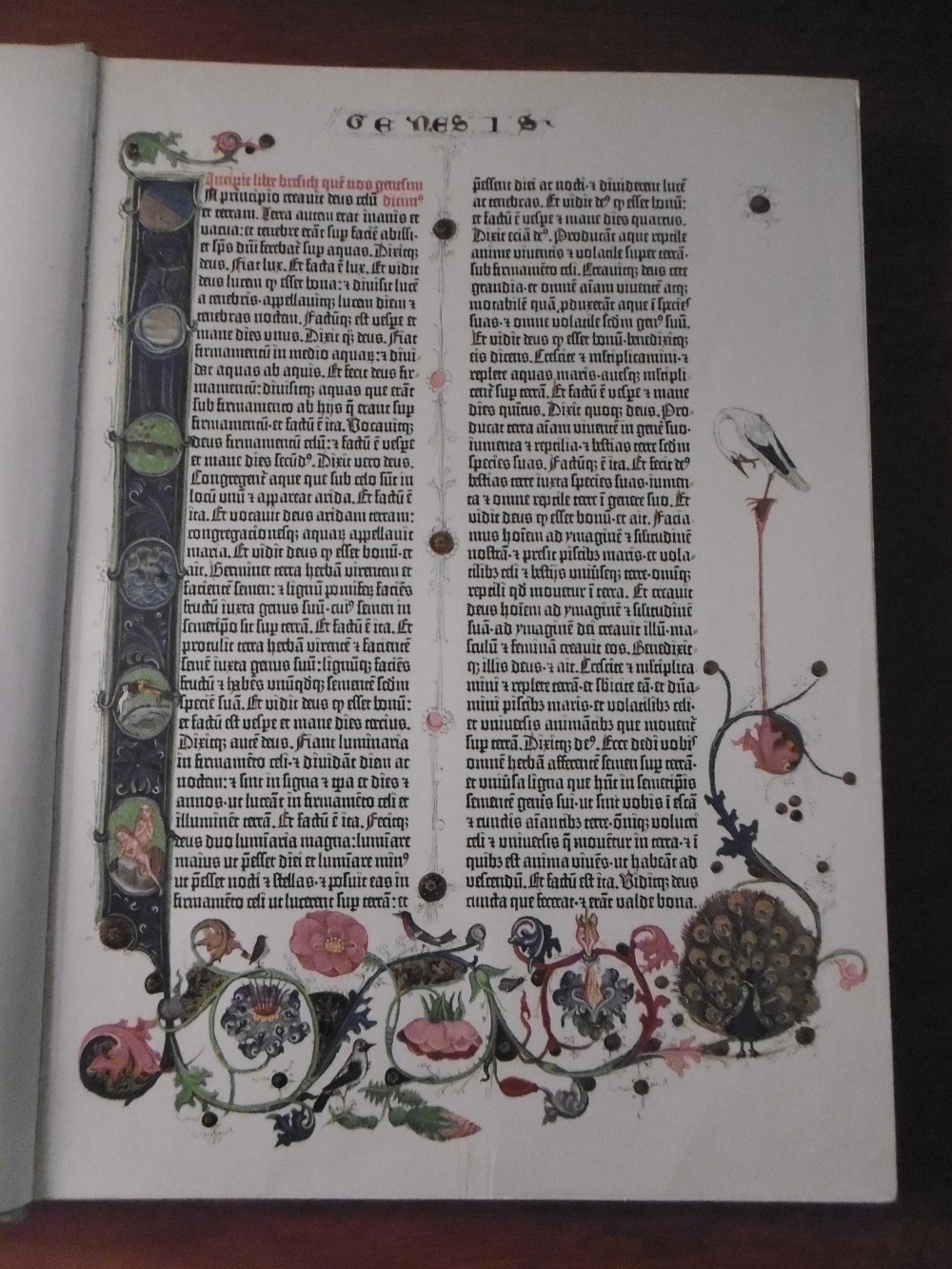

These are facsimiles of Caxton’s 1485 edition of Le Morte d’Arthur and a Gutenberg Bible.

These are facsimiles of Caxton’s 1485 edition of Le Morte d’Arthur and a Gutenberg Bible.

No gloves required.

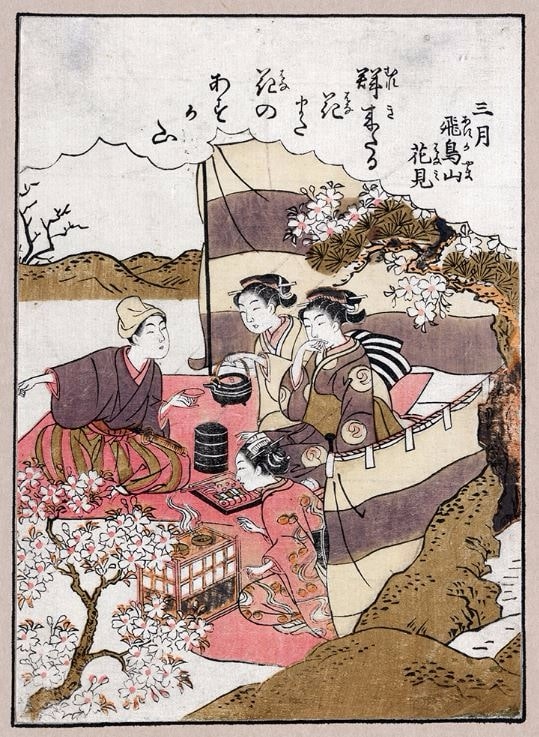

The way opens between hedge rows. Birds chitter within. One enters by a narrow lane, and the world blooms into rosy hues. A soft breeze through branches carries pink petals, fluttering. Well dressed men and women, checkered blankets spread beneath them, clink glasses. Laughing children roll in lush green grass. Tiny birds flit from branch to branch, tree to tree, twittering the news: “Springtime, springtime! Springtime is here!”

I walked into a cherry orchard at the Parc de Sceaux. All the trees were in full bloom, all the people were there to see them, and everyone brought a picnic.

A young man, wearing dark pants and white button-up shirt, set up a camera on a tripod. Its lens, as long as my forearm, extended toward hanging blossoms, dazzling in the sunlight. The hollow pop of a cork leaving a Champagne bottle turned heads and made a girl giggle.

A young man, wearing dark pants and white button-up shirt, set up a camera on a tripod. Its lens, as long as my forearm, extended toward hanging blossoms, dazzling in the sunlight. The hollow pop of a cork leaving a Champagne bottle turned heads and made a girl giggle.

“Is there a party?” I asked, my American accent coming through the French.

“Hanami,” he said with a Japanese accent, “ancient Japanese custom, big spring celebration.”

We chatted for a few minutes while he lined up a shot with the camera. I took a few photos as well and made a note to look up this custom when I got home. This is what I found:

In eighth-century Japan, neighboring Chinese culture was considered more sophisticated. Such was its influence that the Japanese capital, Nara, was modeled after its Chinese counterpart, including numerous plum trees imported from China. In the region, plum trees bloom in late February and mark the end of winter.

Emperor Saga in the early ninth century is credited as the first to throw a party in a blooming orchard. Thus hanami, “flower viewing” in Japanese, began among the elite of the imperial court.

Due to a rebellion in China, that country’s exports to Japan halted. The intercultural rupture is marked by the 894 abolition of Japan’s official delegations to China, which required an arduous crossing of the Sea of Japan. Reduced influence from the mainland allowed an independent Japanese culture to flourish, and the native cherry tree gained in popularity over the plum tree. Blooming at the end of March, cherry blossoms mark the arrival of spring.

History measures the popularity of plum and cherry blossoms by the number of mentions each receives in various ancient texts, such as chronicles, diaries, and poetry, including waka and haiku. So many mentions for plums in this century versus only this many for cherries. The next couple centuries see an increase in cherry mentions and a decrease in plums. Vote for your favorite thing in writing.

Hanami remained a practice of the elite until the eighteenth century. His people suffering from poverty and hunger, Shogun Tokugawa Yoshimune invited local subjects into a private cherry orchard to share in the springtime festival, which included a feast as well as cherry blossoms. The event was well received. The shogun then ordered the planting of cherry trees along rivers and lanes and encouraged the people to participate in the annual event.

Today, hanami is as popular as ever in Japan, and the custom has spread around the world. In France, the trees blossom mid-April, when some 200 Japanese cherry trees attract locals and tourists to two orchards in the Parc de Sceaux, south of Paris.

If you want to see the spectacle, it’s happening this week!

Stephen Wendell lives near the Parc de Sceaux, where he goes for a daily run. He is the author of the Littlelot series of children’s books and The Way to Vict’ry, a book of three haiku inspired by Sun Tzu, Matthieu Ricard, and a magpie flight instructor.

View of the north cherry tree orchard, west of the Grand Canal, Parc de Sceaux. If you miss the pink ones, the white cherry blossoms, in the south orchard farther down the lane, peak a couple weeks later.

Metro line 6 to Bir-Hakeim then a 10-minute walk to the American Library passes by the Iron Lady, wreathed today in bright November.

I love doors. Whenever Catherine and I go exploring in a town or village, I always fall behind because I’m looking at them. I have the idea that you could tell the history of civilization talking about doors.

This one, opposite the corner of rue Monsieur Le Prince and rue Dupuytren, integrates the window above. Check out the carved Earth motif. There are other things in there, too, including a book. I’m going to have to find out who made this door and why.

“Many when they come to die have spent all the truth that was in them, and enter the next world as paupers. I have saved up enough to make an astonishment there.” — Mark Twain

The Phaedra moored on stakes along the Burgundy Canal (photo by Cris Hammond)

The Phaedra moored on stakes along the Burgundy Canal (photo by Cris Hammond)

The Phaedra is a flat-bottom barge, 56 feet long and not twice as wide as my outstretched arms. Originally a commercial craft, she was put to service in 1925, hauling milk and cheese along the waterways between Holland and Belgium. At the time, a barge was pulled by men or horse along canals. For river navigation, she was built with a single mast. Made obsolete by a combustible engine, the mast now lies fixed over the main cabin.

I asked Cris what happened to the Phaedra during the war. He said none of his papers about the boat give any clue and suggested I make something up. So let’s imagine for a moment…

During World War II the Phaedra was requisitioned by the German army to ferry troop supplies from the Netherlands, through Belgium and into occupied France. Unknown to the Germans, the Dutch bargeman, whose name was Raemaekers, also carried coded messages between French resistance fighters and spies in Holland, who transmitted the messages to General de Gaulle in London.

Raemaekers almost got caught in early June, 1944. At Charleville, a port town on the Meuse, northern France, a German officer stumbled onto the scene during the message exchange. The bargeman fled on foot with the resistance operative, a French woman he called Angelica. Taken in by an old spinster and hidden in the cellar, the two spent a torrid night in each other’s arms.

The following day news of the Normandy invasion caused mayhem in the town. That night, Raemaekers slipped aboard the Phaedra and, learning that the Germans had blocked downstream traffic to allow shipments to the front, he made his escape south, up river. Angelica, continuing the mission, took the message north.

For months, Raemaekers navigated rivers and canals through occupied territory. He made it as far as Saint-Jean-de-Losne (pronounced /lohn/), at the end of the Burgundy Canal. As he pulled the Phaedra through the last lock into the Saône River, a series of three explosions cracked the air. The German army had blown up the bridge over the river to cover their retreat ahead of advancing Allied troops from the south.

Though he tried to track her down after the war, Raemaekers never saw Angelica again.

The entire story is documented in a book called The Phaedra Adventure, and none of this is true.

It is true, however, that the Phaedra was converted to a pleasure barge in the late 1940s. The cargo hold became a small apartment, complete with kitchenette, living area, two staterooms, two toilets and a shower. Also installed at this time, a pair of stained glass windows filter outside light from the pilothouse into the living area.

Amphitrite (left) and Poseidon in stained glass

Amphitrite (left) and Poseidon in stained glass

The windows depict Poseidon and Amphitrite, god and goddess of the sea. In Greek mythology, Phaedra is the daughter of Minos, first king of Crete, and Pasiphaë, who also gave birth to the Minotaur. The father of Minos was Zeus, brother of Poseidon. So the stained glass god and goddess are great uncle and aunt to Phaedra, and her half-brother is the Minotaur.

Before Cris, the Phaedra’s owner was a doctor and master woodcarver, who bought the barge in the 80s. In addition to fitting a new engine, he carved nautical and floral motifs in the wood trim, including the wheel pedestal.

Cris became the proud new owner in 2001 at Saint-Jean-de-Losne. He painted her in greens and blues. It’s a lovely palette for a barge that is today a veritable work of art. I’ve seen tourists strolling along the quay stop to take photographs and selfies with the Phaedra.

Between Poseidon and Amphitrite hangs a brass plaque with an inscription in Dutch: “BY BRAND DEZE PLAAT OMDRAAIEN”

Thinking it must be a motto, I asked Cris what it meant. He said, “Reverse this plaque in case of fire…”

The car rental manager in Rethymno, Crete: “What’s the problem?”

“A slow leak in the left rear tire,” I said. “I have to put air in it every morning.”

A thick layer of dust covered the car. He gave it the once over, hands on hips.

“Where have you been?”

In light of the present problem, I didn’t want to admit that I’d driven the compact to the furthest reach of a gravelly, pot-holed two-track at the end of Rodopos Peninsula.

“I’ve been all over your wonderful island.”

That was at least the truth. Although I hadn’t done it all during this latest trip.

He nodded at the rear window, opaque with dust. “Do you see anything?”

“I never look back!”

Young Gordy spends mornings combing the beach for flat stones. He spends afternoons skipping them across low rolling waves into the sea, then diving to retrieve them again.

If, during his lunch, the wind blows too strong and kicks up the surf, Gordy buries the flat stones in the dune to find them the next day.

A map of your failures

reveals the path to your success.

My plan to become a fiction writer is highly speculative:

But what if… I do it anyway?