The way opens between hedge rows. Birds chitter within. One enters by a narrow lane, and the world blooms into rosy hues. A soft breeze through branches carries pink petals, fluttering. Well dressed men and women, checkered blankets spread beneath them, clink glasses. Laughing children roll in lush green grass. Tiny birds flit from branch to branch, tree to tree, twittering the news: “Springtime, springtime! Springtime is here!”

I walked into a cherry orchard at the Parc de Sceaux. All the trees were in full bloom, all the people were there to see them, and everyone brought a picnic.

A young man, wearing dark pants and white button-up shirt, set up a camera on a tripod. Its lens, as long as my forearm, extended toward hanging blossoms, dazzling in the sunlight. The hollow pop of a cork leaving a Champagne bottle turned heads and made a girl giggle.

A young man, wearing dark pants and white button-up shirt, set up a camera on a tripod. Its lens, as long as my forearm, extended toward hanging blossoms, dazzling in the sunlight. The hollow pop of a cork leaving a Champagne bottle turned heads and made a girl giggle.

“Is there a party?” I asked, my American accent coming through the French.

“Hanami,” he said with a Japanese accent, “ancient Japanese custom, big spring celebration.”

We chatted for a few minutes while he lined up a shot with the camera. I took a few photos as well and made a note to look up this custom when I got home. This is what I found:

In eighth-century Japan, neighboring Chinese culture was considered more sophisticated. Such was its influence that the Japanese capital, Nara, was modeled after its Chinese counterpart, including numerous plum trees imported from China. In the region, plum trees bloom in late February and mark the end of winter.

Emperor Saga in the early ninth century is credited as the first to throw a party in a blooming orchard. Thus hanami, “flower viewing” in Japanese, began among the elite of the imperial court.

Due to a rebellion in China, that country’s exports to Japan halted. The intercultural rupture is marked by the 894 abolition of Japan’s official delegations to China, which required an arduous crossing of the Sea of Japan. Reduced influence from the mainland allowed an independent Japanese culture to flourish, and the native cherry tree gained in popularity over the plum tree. Blooming at the end of March, cherry blossoms mark the arrival of spring.

History measures the popularity of plum and cherry blossoms by the number of mentions each receives in various ancient texts, such as chronicles, diaries, and poetry, including waka and haiku. So many mentions for plums in this century versus only this many for cherries. The next couple centuries see an increase in cherry mentions and a decrease in plums. Vote for your favorite thing in writing.

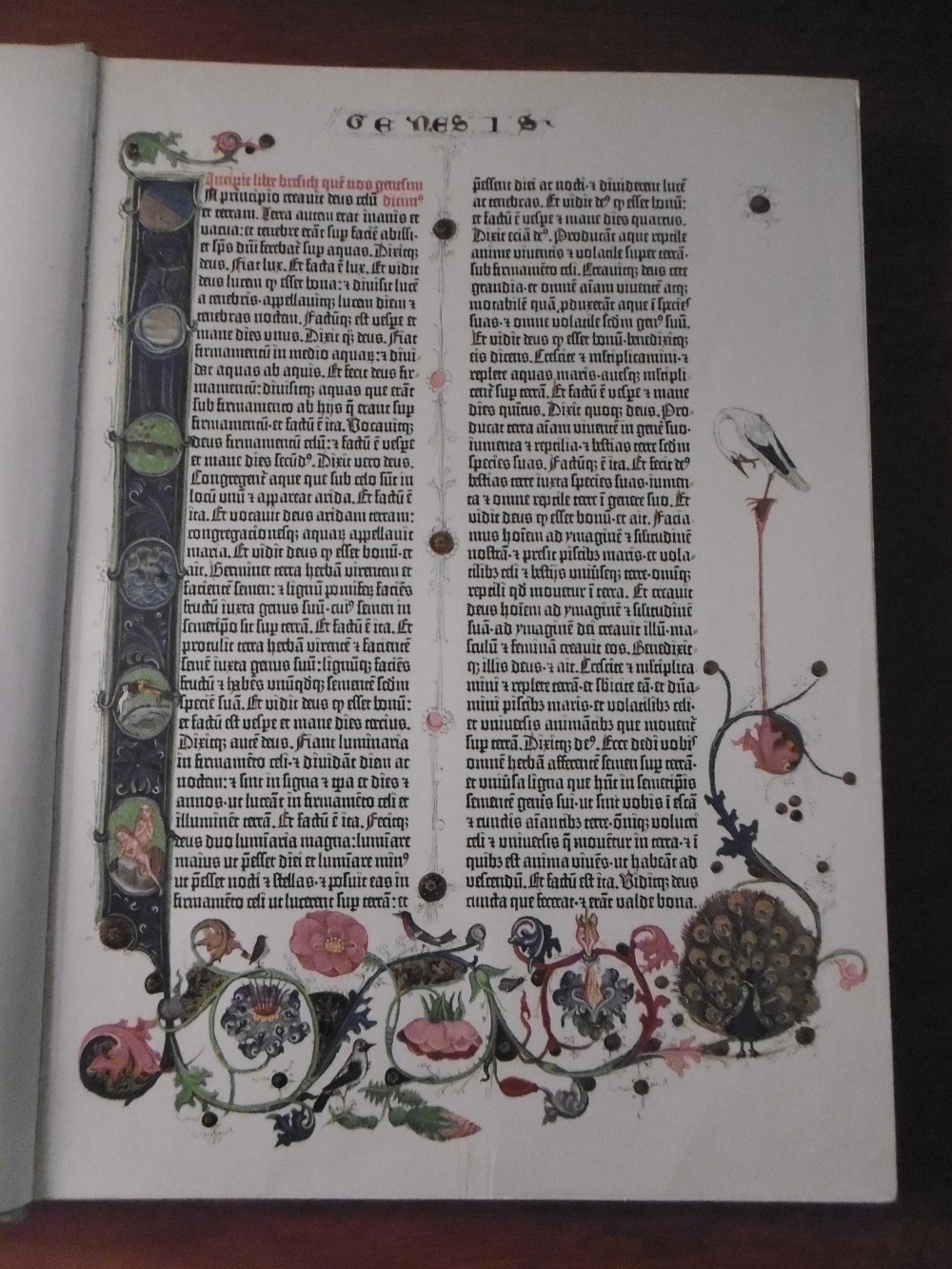

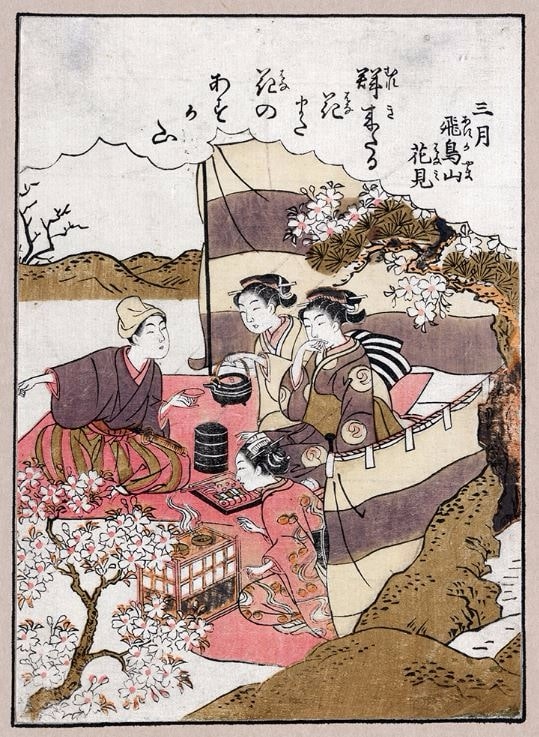

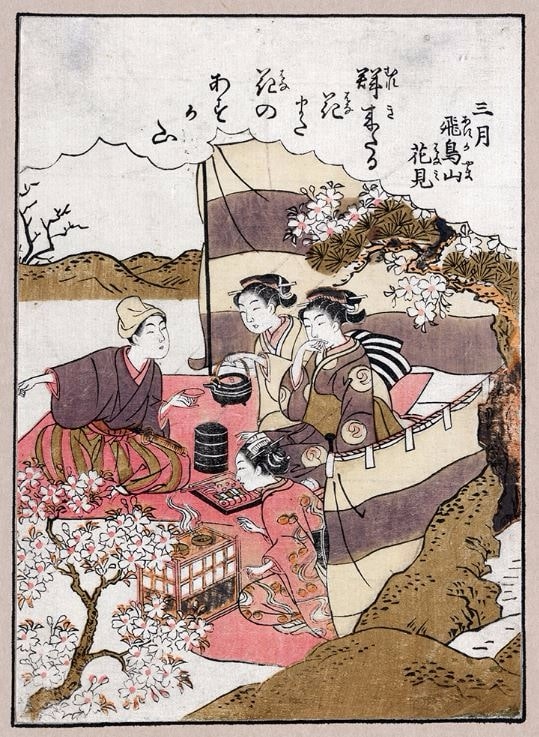

Yayoi or Sangatsu, Asukayama Hanami (Third Lunar Month, Blossom Viewing at Asuka Hill) by Kitao Shigemasa (1739–1820), from the series Jūnikagetsu (Twelve Months), between 1772 and 1776. Color woodblock print. Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress.

Hanami remained a practice of the elite until the eighteenth century. His people suffering from poverty and hunger, Shogun Tokugawa Yoshimune invited local subjects into a private cherry orchard to share in the springtime festival, which included a feast as well as cherry blossoms. The event was well received. The shogun then ordered the planting of cherry trees along rivers and lanes and encouraged the people to participate in the annual event.

Today, hanami is as popular as ever in Japan, and the custom has spread around the world. In France, the trees blossom mid-April, when some 200 Japanese cherry trees attract locals and tourists to two orchards in the Parc de Sceaux, south of Paris.

If you want to see the spectacle, it’s happening this week!

Stephen Wendell lives near the Parc de Sceaux, where he goes for a daily run. He is the author of the Littlelot series of children’s books and The Way to Vict’ry, a book of three haiku inspired by Sun Tzu, Matthieu Ricard, and a magpie flight instructor.

View of the north cherry tree orchard, west of the Grand Canal, Parc de Sceaux. If you miss the pink ones, the white cherry blossoms, in the south orchard farther down the lane, peak a couple weeks later.

Oliver Rackham, 1939-2015

Oliver Rackham, 1939-2015 Zelkova abelicea, circa 1300-

Zelkova abelicea, circa 1300-

I met Tom at a café I call the field office. Tom teaches history of religion to high school sophomores in Arizona. He comes to Paris every year to do research at the Bibliotèque François Mitterrand.

I met Tom at a café I call the field office. Tom teaches history of religion to high school sophomores in Arizona. He comes to Paris every year to do research at the Bibliotèque François Mitterrand.

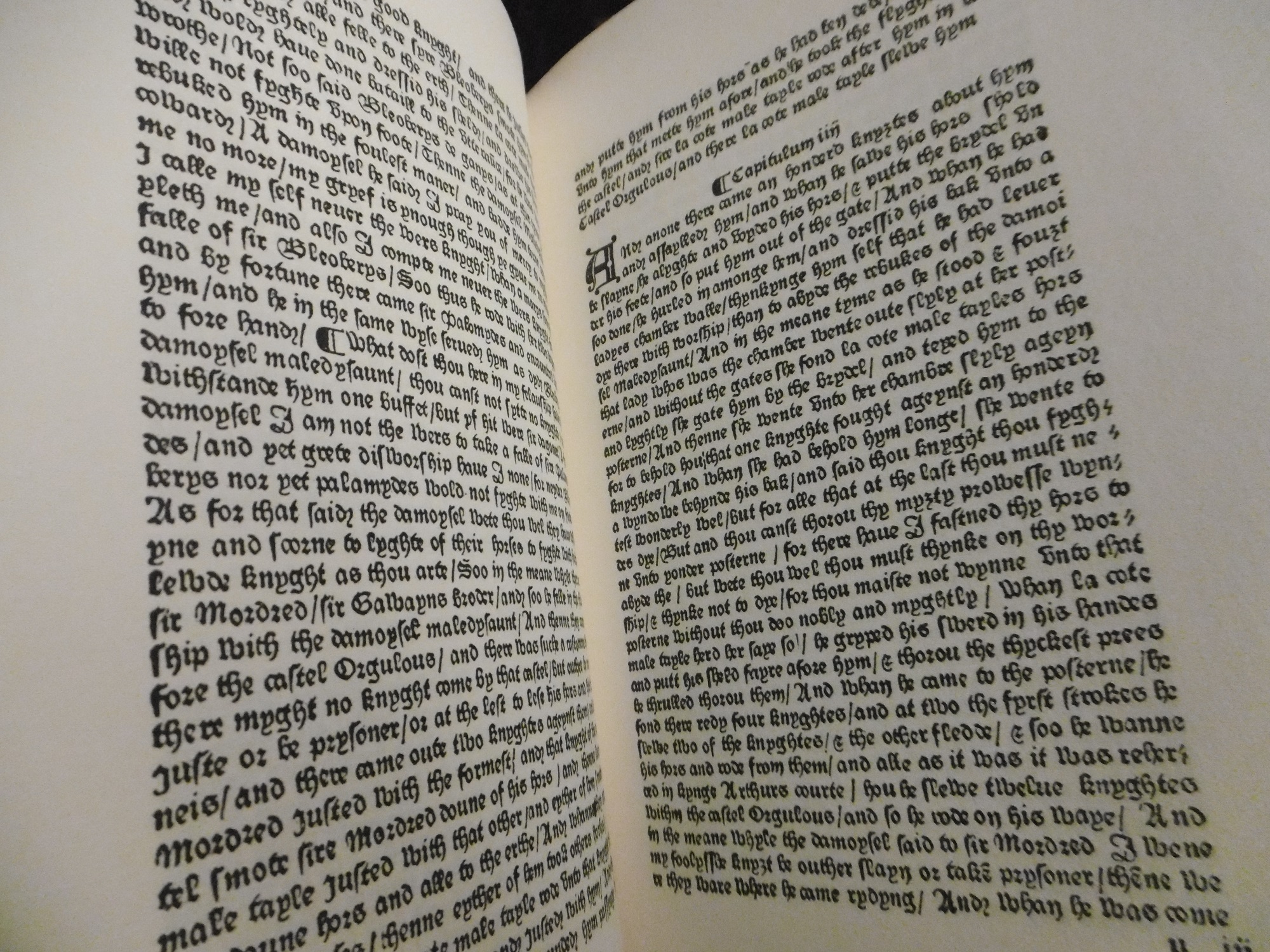

Tom gave me a tour. We got as far as the rare book reserve…

Tom gave me a tour. We got as far as the rare book reserve…