Cretans, as a people, are kind and proud and fierce. I said so to a friend after one of many sojourns to the Isle of Myth.

“All Cretans are liars,” he said.

I said, “That’s a lie.”

“Of course it is; a Cretan said it!”

Epimenides is a legendary figure. He lived in the seventh and sixth centuries BC. He was a poet, philosopher, ascetic, wise man, prophet, and—according to his own countrymen—a god.

Diodorus Siculus, first-century-BC historian of ancient Greece, called Epimenides a theologian and a trustworthy authority on Cretan affairs (Epimenides Fragment 20). In the second century AD, Christian philosopher Clement of Alexandria wrote in The Stromata that Greeks of his time counted Epimenides among the seven (or nine) men most admired for their wisdom.

In the third century, Diogenes Laërtius treats Epimenides in The Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers. Most of what we know about his life comes from this biography.

Of his youth, Diogenes tells the following legend, which I summarize: While tending sheep one summer day, Epimenides sought shelter from the sun in a cave, where he took a nap. He woke up fifty-seven years later, untouched by age. When folk heard the story, they took him for a favorite of the gods.

His parentage is disputed among ancient historians, but all agree that Epimenides was born and lived in Knossos. Unlike Cretans of the day, he let his hair grow long, and tattoos covered his skin. He ate rarely, in small quantities, and only food provided by nymphs. He purified cities, built shrines and temples, and was given to prophesying.

Though age caught up with him fifty-seven days after his waking, Epimenides lived on to write poetry as well as prose, which Diogenes describes:

He wrote a poem of five thousand verses on the Generation and Theogony of the Curetes and Corybantes, and another poem of six thousand five hundred verses on the building of the Argo and the expedition of Jason to Colchis.

He also wrote a treatise in prose on the Sacrifices in Crete, and the Cretan Constitution, and on Minos and Rhadamanthus, occupying four thousand lines. (Lives, 51)

None of these writings, however, survived the intervening millennia. We know of Epimenides through biographers and fragments of his work in later texts.

One such text is St. Paul’s Letter to Titus, then bishop of Crete. The epistler calls on Titus to reprimand those who rebel against the faith.

They must be silenced, because they are disrupting whole households by teaching things they ought not to teach—and that for the sake of dishonest gain. One of Crete’s own prophets has said it: “Cretans are always liars, evil brutes, lazy gluttons.” This saying is true. Therefore rebuke them sharply, so that they will be sound in the faith. (Titus 1:11-13)

Clement, again in The Stromata, identifies Epimenides as the Cretan prophet of Paul’s letter:

… Epimenides the Cretan, whom Paul knew as a Greek prophet, whom he mentions in the Epistle to Titus, where he speaks thus: “One of themselves, a prophet of their own, said, The Cretans are always liars…” (Stromata 1.14)

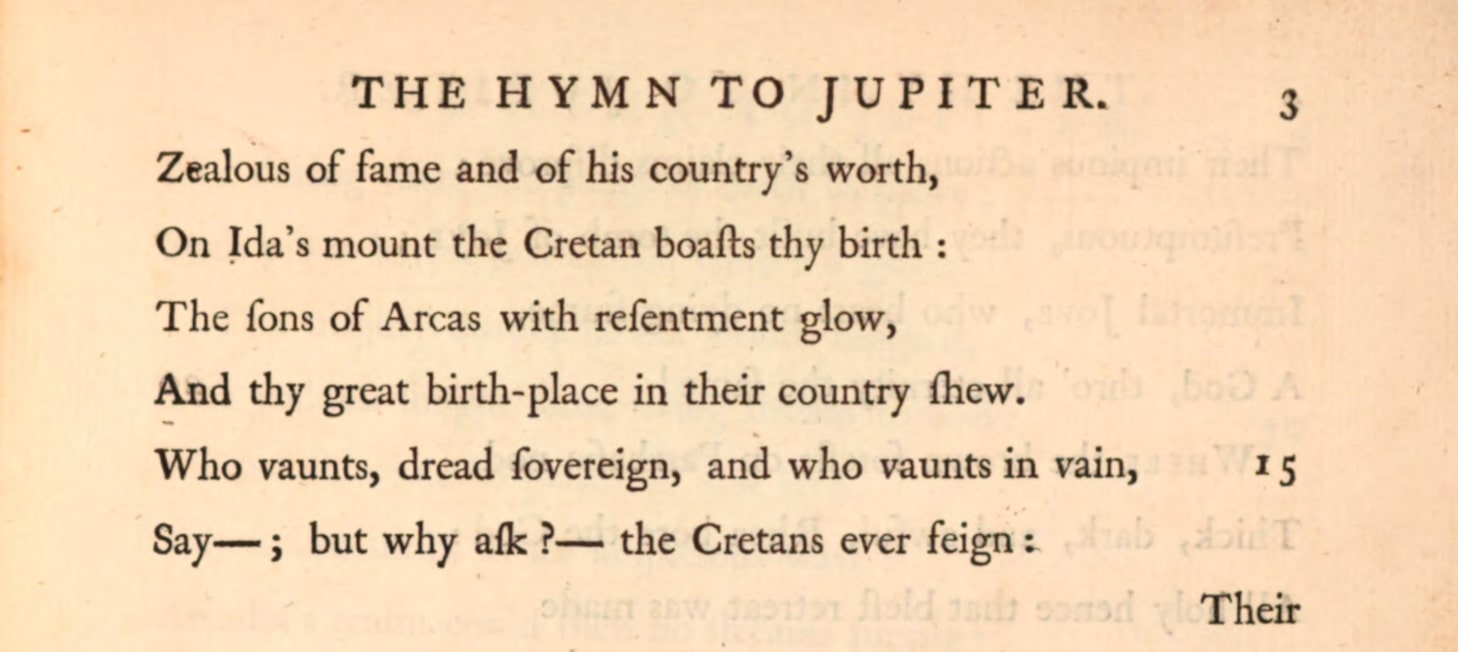

Some 300 years after Epimenides, Greek poet Callimachus writes: “The Cretans ever feign.” In his Hymn to Zeus, it is the tomb of the father of gods and men—which the Cretans say is in their country, therefore blasphemy—that prompts the denigrating remark.

“The Cretans ever feign” from “The Hymn to Jupiter” translated by William Dodd in The Hymns of Callimachus (London: T. Waller and J. Ward, 1755).

“The Cretans ever feign” from “The Hymn to Jupiter” translated by William Dodd in The Hymns of Callimachus (London: T. Waller and J. Ward, 1755).

Callimachus doesn’t mention Epimenides. We will see below, however, that the scenario is borrowed from the Knossian prophet—or at least the two writers share a common source.

Though Epimenides’ work is lost, Paul’s Letter to Titus was collected into a large volume, which is both respected for its veracity and widely circulated. And so, what has become known as Epimenides’ Paradox[1] comes down to our times.

In the early twentieth century, biblical scholar and manuscript hunter J. Rendel Harris found evidence linking Paul’s quote with the scenario given by Callimachus. The discovery was made in successive steps. Here, I make short the process, which Harris documents in three articles over five years in a theological journal.[2]

Ishodad of Merv was a theologian of the Nestorian Church, a branch of Eastern Christianity. In the ninth century, he wrote extensive commentary on the Old and New Testaments.

Among Ishodad’s commentary, Harris discovered a familiar refrain concerning Cretans: “Liars, evil beasts, idle bellies.” It is one of a four-line verse describing the same scenario given by Callimachus. And the verse is part of an excerpt summarizing the work of a fourth-century theologian, Theodore of Antioch, called “The Interpreter,” because Theodore’s works were considered heresy.

Furthermore, the excerpt gives the verse as dialog, part of a speech by Minos, mythical King of Crete.

In one article (The Expositor, Oct. 1912), Harris reproduces the text, of which the following is part:

The Cretans said about Zeus, as if it were true, that he was a prince, and was lacerated by a wild boar, and was buried; and behold! his grave is known amongst us; so Minos, the son of Zeus, made a panegyric [speech of elaborate praise] over his father, and in it he said:

The Cretans have fashioned a tomb for thee, O Holy and High!

Liars, evil beasts, idle bellies;

For thou diest not; for ever thou livest and standest;

For in thee we live and move and have our being.

So the blessed Paul took this sentence from Minos.

The final phrase, according to Harris, intends a work by Epimenides, possibly a short title for “Minos and Rhadamanthus,” mentioned by Diogenes.[3]

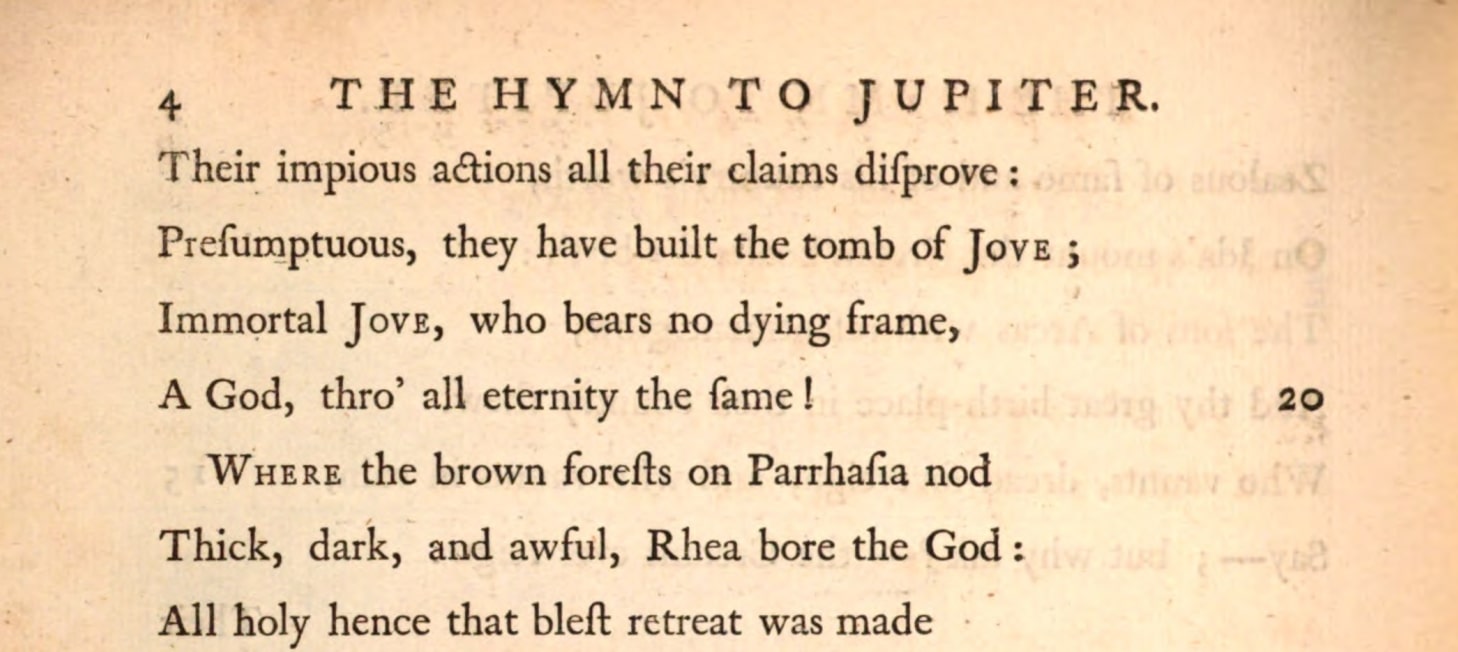

“They have built the tomb of Jove…, who bears no dying frame” from Dodd, who translates the Greek Zeus to the Roman Jupiter and Jove.

“They have built the tomb of Jove…, who bears no dying frame” from Dodd, who translates the Greek Zeus to the Roman Jupiter and Jove.

If we accept the character’s existence at all, Minos was a first generation Cretan. So, while we now better understand the context, the paradox remains.

Diogenes writes that Epimenides died at 299 years of age—“as the Cretans report.”

[1] The paradox is sometimes called the “Fallacy of Mentiens,” especially in turn-of-the-twentieth-century textbooks on Logic, e.g. Fowler (1883), Gibson (1914), Bartlett (1922). Diogenes, in another entry of Lives, gives a long list of works by Chrysippus, a philosopher who wrote 200 years after Epimenides. A few of Chrysippus’s titles, grouped together, refer to “the Mentiens Argument.” Among this group, another title is “Reply to those who hold that Propositions may be at once False and True.”

[2] I refer interested readers to Harris’s articles published in The Expositor available on the Biblical Studies website: “The Cretans Always Liars” (Oct. 1906):305-317, “A Further Note on the Cretans” (Apr. 1907):332-337, and “St. Paul and Epimenides” (Oct. 1912):348-353. For more about Harris’s quest for ancient texts, consider his biography by Alessandro Falcetta, The Daily Discoveries of a Bible Scholar and Manuscript Hunter: A Biography of James Rendel Harris (1852–1941).

[3] Ishodad’s excerpt comes from his commentary on Acts of the Apostles. In the text above, “this sentence” refers to the last line of Minos’s dialog, which St. Paul quotes in his speech to the Areopagus (Acts 17:28). For more about references to Epimenides in Titus and Acts, see Paul Davidson’s informative article, “Lying Cretans and Unknown Gods: Allusions to Epimenides in the New Testament,” on Is That in the Bible?

Twenty-first-century author Stephen Wendell is writing a novel set in mythological Crete.