“When you’re curious, you find lots of interesting things to do.”—Walt Disney

Akrotiri Spada is the northernmost point of Crete and the very end of Rodopou Penninsula. It’s marked by Zovigli, a conical hill that rises 70 meters above the surrounding terrain, which is 300 meters above the sea. Evenly spaced around the northern half of Zovigli’s base, oval shadows belie cave openings, the objective of our present expedition.

Zovigli hilltop (upper right), elevation 370 meters

Lightly clothed against unseasonal April heat, wearing a hat and sunscreen against the rays, I carried in pockets a camera, a small flashlight, a pocket knife, and the dumbphone. A one-hour drive along a rough, gravel road took me to the start point, a lone farmhouse near the end of Rodopou.

Peninsulas Gramvousa (left) and Rodopou define Kissamos Bay

Akrotiri Spada is named after its shape on a map. In Latin characters, the Modern Greek spelling is Spatha, which means “broad blade” or “sword,” and akrotiri means “cape.” Exploring is more fun in a place called Sword Cape.

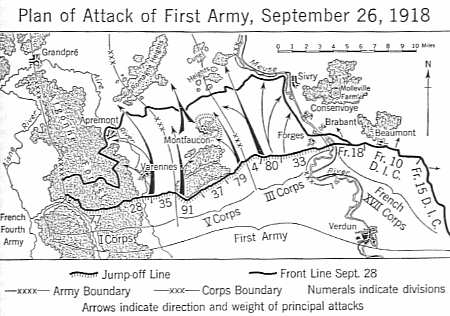

A dirt track, impassable by car, leads two kilometers to the peninsula’s point. There, the hill is surrounded by several structures, including an empty concrete building, the remains of two stone-built towers, and a goat pen, the inhabitants of which roam free across the rocky landscape. The concrete building is certainly a wartime construction, built by German soldiers during the WWII occupation of Crete. The two round towers, both on the cliff’s edge overlooking the sea, were used by the Germans, but they may have been built earlier, possibly by the Venetians.

Looking west from the point of Akrotiri Spada, a ruined stone tower overlooks the Sea of Crete; beyond is the point of Gramvousa Peninsula

A shrub called thorny cushion attacks exposed flesh below the knee

On approach to the hill, I surprised a goat kid, who put out a call to its mother. The nanny, on the hillside some distance away, returned the call and started down, while their herd-mates expressed displeasure at the unexpected visit. So, to a chorus of bleating goats, I picked my way over uneven terrain, up the hill toward a shadowy opening, avoiding sharp stones, holes, and thorny-cushion shrubs.

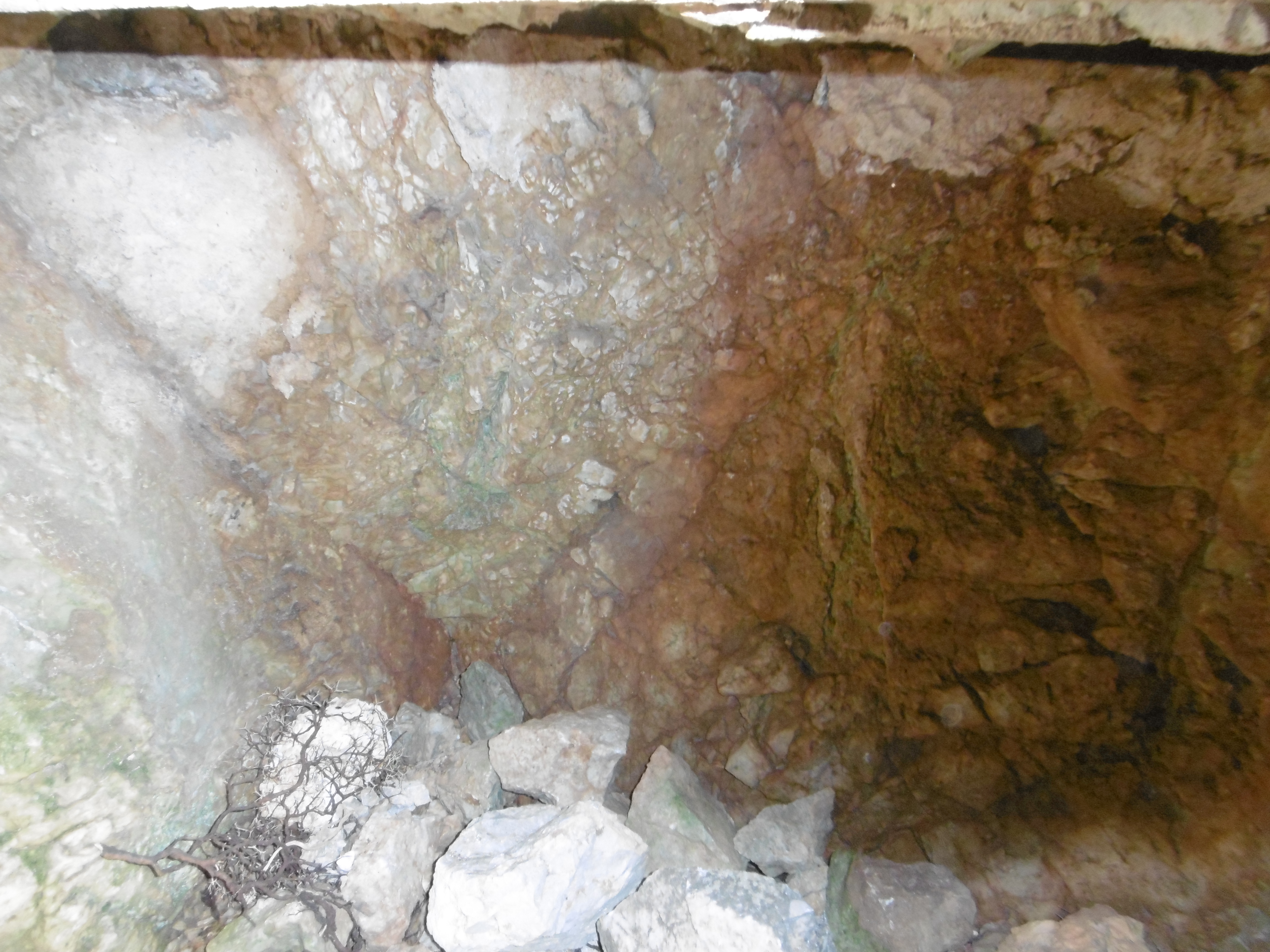

Beyond the cave openings are tunnels, blasted out of the stone hill by the Germans. The tunnels extend up to 50 feet straight into the hill. Inside, green moss grows in thin film on the walls near the entrances; a layer of goat droppings covers the floors. Bore holes in the rear of each tunnel give away the digging method: drill a hole a couple feet deep and the diameter of a dynamite stick, insert explosives, stand back and hold your ears, then clear out the rubble.

In front of the tunnels are gun emplacements and various structures I guessed were once headquarters and mess hall. Each emplacement is connected to the next by a man-height trench, also blasted out of solid rock.

Gun emplacement at 3., tunnel behind

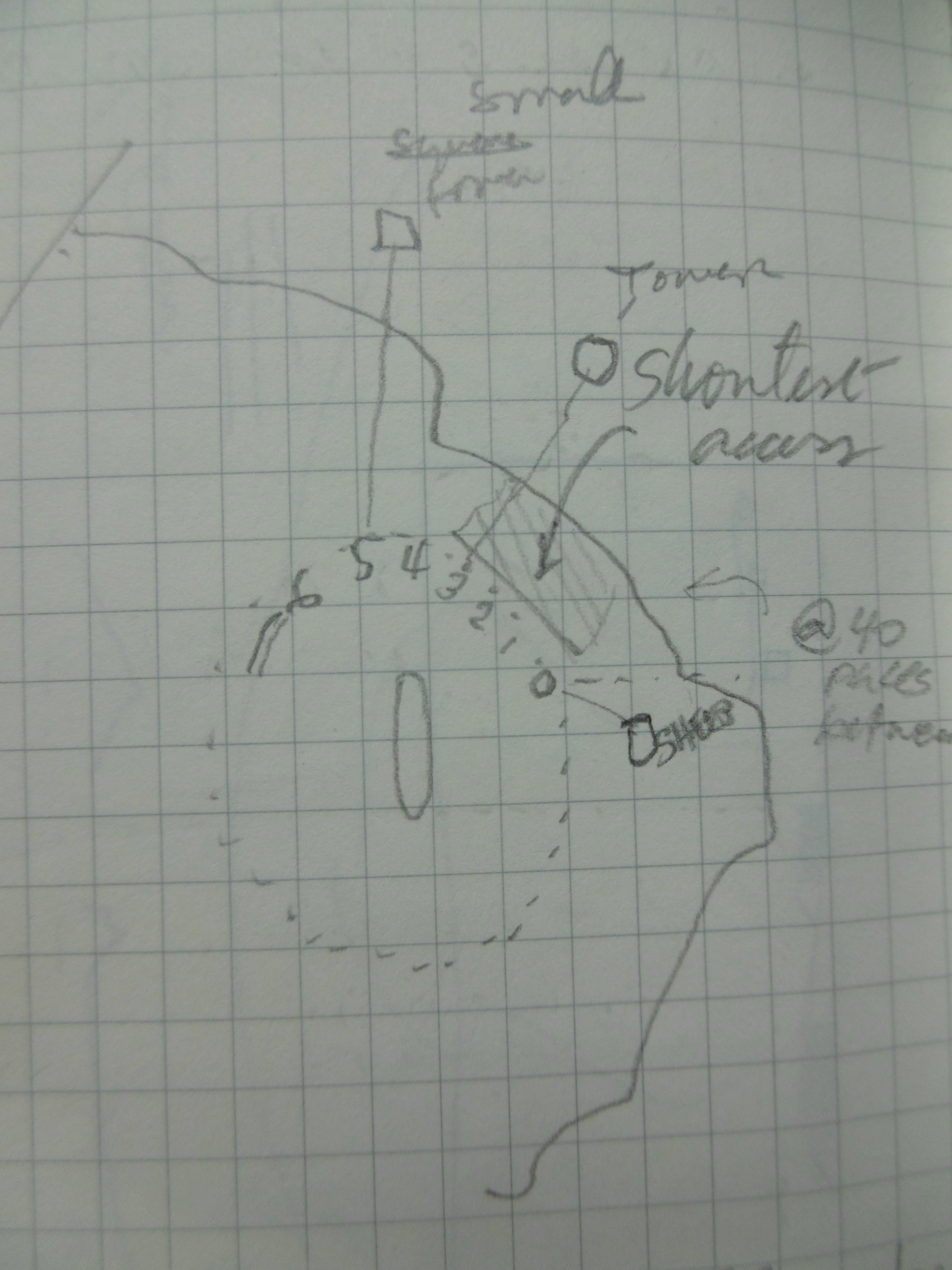

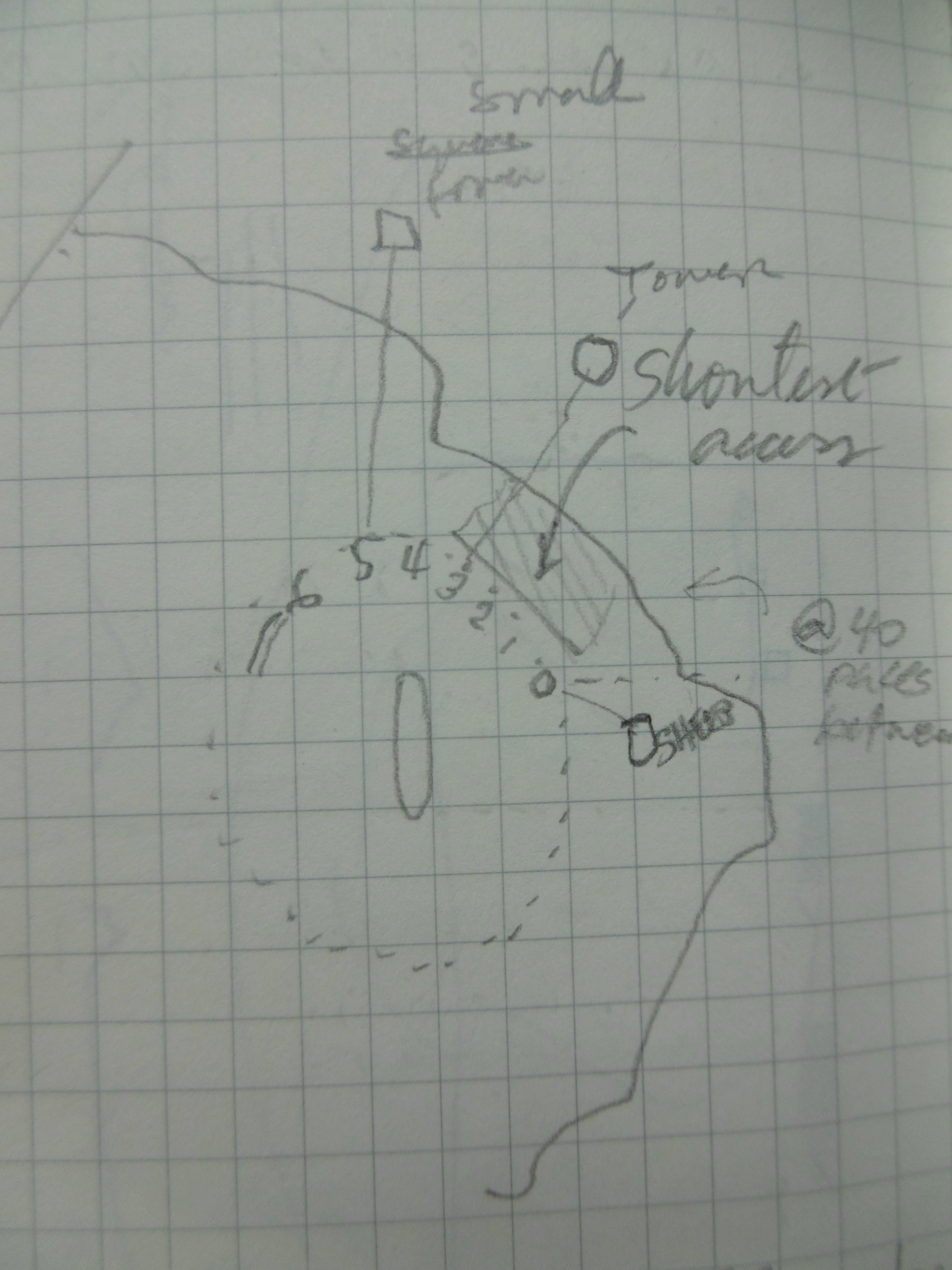

In all, I counted five tunnels. The trench leading east from the easternmost tunnel, which I refer to as the first or 1., leads to a large hole. Its purpose I could not guess.

In the opposite direction from the first tunnel, the trench leads to a rock slide. Pacing my steps, I counted—roughly, due to difficult footing—forty to fifty paces between each of the other tunnels. However, moving west from the first through the rock slide to the next tunnel, I measured twice the distance. Therefore, I presume the rock slide must cover another tunnel or some such emplacement.

Field sketch showing emplacements around Zovigli’s base

Emplacements from east to west:

0. Hole, trench begins

1. Gun emplacement and tunnel

2. Rock slide (buried emplacement?)

3. Gun emplacement and tunnel

4. Headquarters, tunnels on either side

5. Mess hall and forked tunnel

6. Depot, trench ends, road begins

What I call the “depot” (6.) is the foundation of a small rectangular building. An old track, now grassed over, starts there and goes a hundred feet or so before becoming lost in stones and thorny cushions.

Looking up the west face, it didn’t seem so very far to the top. I was ill equipped for climbing, shod in flat sandals. However, I knew from earlier satellite reconnaissance there was a rectangular structure up there, and this might be my only chance to explore it. So, I screwed on my hat, stuck the Arizonas to my feet, and scrambled to the top.

From Zovigli hilltop, 370 meters above, a tour boat rounds the cape

I was alone, but there were witnesses. I reached the pinnacle and looked down. Passengers aboard a tour boat, likely on its way back from the remote beach at Diktynna, must have been saying, “Look, there’s a guy climbing up there!” and “Oh my God, he must be crazy.” I posed for photos.

The rectangular structure may be another wartime construction. Two by three paces in area, five feet high, the four stone block walls and a similar floor are in better shape than the ruins below. In one corner, a two-foot square opening in the floor captures one’s attention. Four rusty rungs set into the stone lead down a few feet. Below that, only a flat rock floats in cool darkness.

Stone block ruins atop Zovigli from above

A debate raged in my head. There was much swearing. I really wanted to see what was down there. I could have descended the rungs and hung a leg down to test the distance to the rock, but if I so much as lost a sandal in that hole, the return hike would be grueling. And much worse than that was well within the realm of possibility. After more minutes than sanity should have allowed, prudence won out.

On the highest rock, there is a cement column, which serves as a geological marker, beside a cairn. The latter indicates the place has been visited by at least a score of other climbers since the Germans left. I found a suitable example to add to its height.

Up there, it was just me and the wind, with the rocks and the sea and the whole world below.

Tell me again, Jonathan Livingston, what is the perfect speed…?

A Bonelli’s eagle, common in Crete

Oliver Rackham, 1939-2015

Oliver Rackham, 1939-2015 Zelkova abelicea, circa 1300-

Zelkova abelicea, circa 1300-