Planning the Meuse-Argonne Offensive

Below, I’ll detail the battle plan where it concerns Private B. F. Potts of Company M, 137th Infantry Regiment. For the moment, I’ll rely on Kenamore, who ably describes the stakes in the Meuse-Argonne Offensive, which will begin in two days—a hundred years ago.

At the conference of allied leaders when the great general attack was planned, the French commander in chief asked:

“Where will the American army fight in this battle?”

“Wherever you wish it to fight,” Gen. Pershing replied.

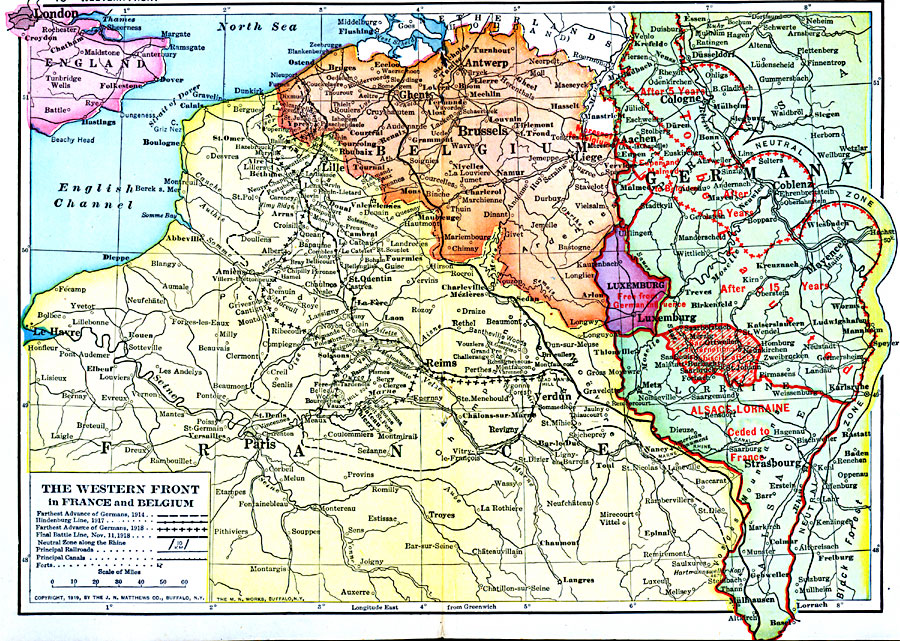

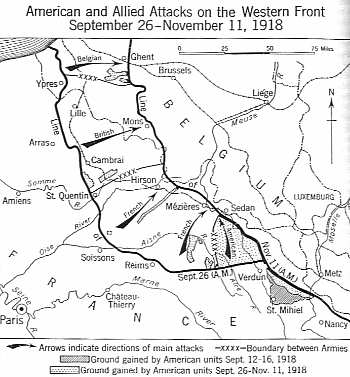

Gen. Foch then indicated the line between the Meuse and the Argonne, and asked if they would take that part of the line. Gen. Pershing assented. It was the part of the line where the heaviest fighting undoubtedly would be if the battle plans worked out, and if the judgment of the military men proved true. Every officer present knew that. The allies were at a point in the operation where a continuation of their strokes would drive the enemy out of France, or he would suffer disaster, possibly annihilation of his armies in the field. To get his armies out, he must maintain his communications, the four-track railroad at Mezieres in front of us, and the business of the Americans was to threaten, and if possible to cut his communications.

It was a field where there was a certainty of the hardest fighting. It was probable that the Germans would bring their best battalions there to make the vital fight. As a consequence, there could be no spectacular gains on the American front. Every foot of ground would be contested bitterly, and those who advanced must pay the price. While on other fronts, large and glittering gains would be made in a day, it would be against a retreating foe, and he would be retreating all the more hurriedly because of the pressure the Americans were bringing on his vitals. The enemy could not retreat on our front. If he did, we would cut his railroads and the French and British to the west of us would capture his armies. It was with a full understanding of what was ahead that the American commander took this post of high honor, where hard blows were to be given and taken, and where there was little to gain.

From Vauquois Hill to Exermont 76-77

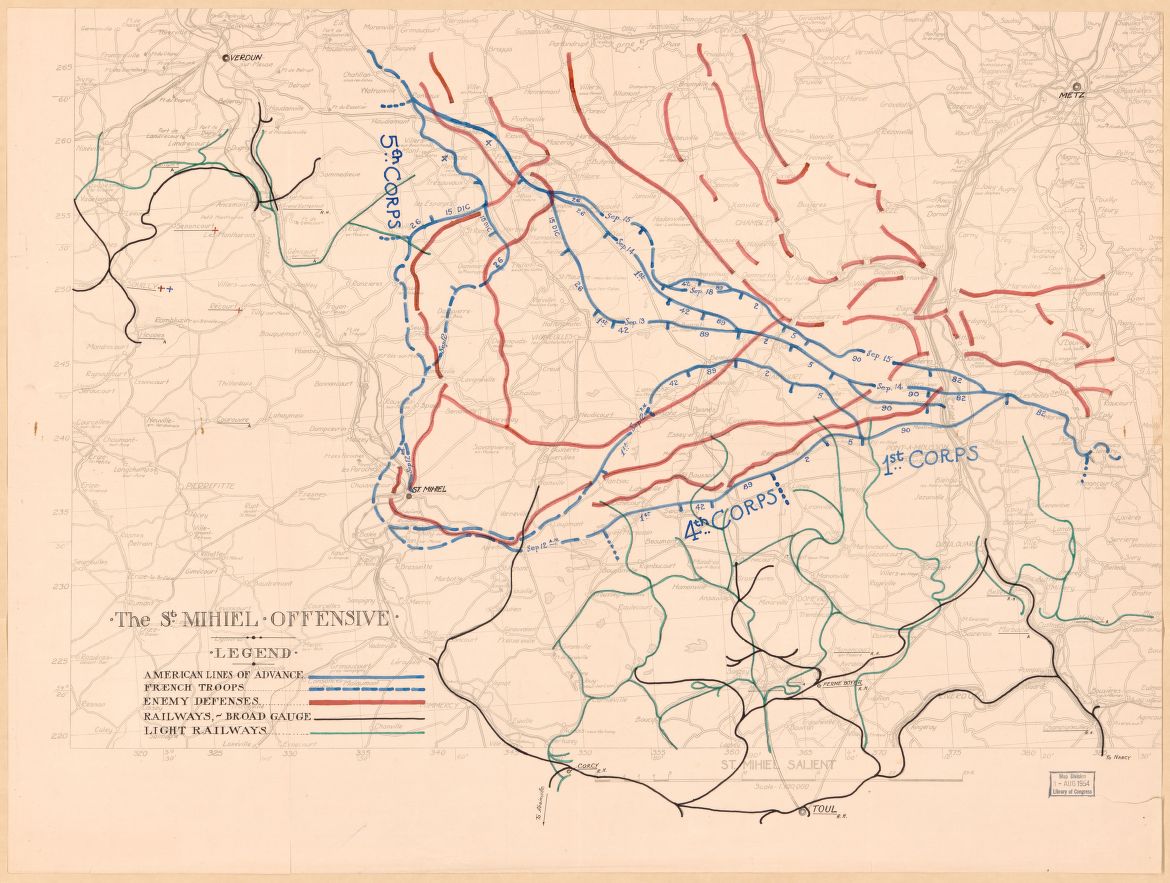

French General Foch’s plan to push the German Army out of his country; the American First Army is in the south near Verdun

French General Foch’s plan to push the German Army out of his country; the American First Army is in the south near Verdun

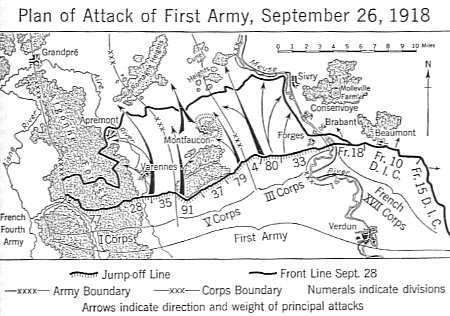

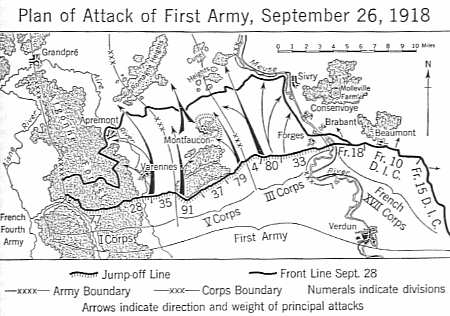

Between the rivers Aisne and Meuse, the I, III, and V Corps of the American First Army were positioned across a 20-mile front. Each corps had three divisions on the line. I Corps’ 77th, 28th, and 35th Divisions held the left, from the Aisne to the Butte of Vauquois. At the foot of the butte, also called Vauquois Hill, the 35th was arrayed for battle.

Part of I Corps, the 35th Division is positioned east of the Argonne Forest

According to Pershing’s plan, the First Army’s nine in-line divisions were to advance at 5:30 a.m., following an artillery preparation. In industrial age battles, artillery fire is used to “prepare the terrain” prior to an infantry advance. Lasting from a few minutes to a few hours, an artillery barrage destroys fixed works and equipment, blows holes in barbed wire barriers, and disrupts enemy activity at intersections in his communication lines. Where it doesn’t injure or kill the enemy, it puts the fear of God into him.

At the time of attack, “H-hour”, the artillery shifts its fire to what’s called a “rolling barrage.” This is a line of devastation 100 meters (roughly 100 yards) in front of the advancing infantrymen, which, in this case, is supposed to move at 100 meters every four minutes. It’s rare that the artillery men can see the line. Therefore, the infantry is obliged to advance at the set pace. Too slow, and he loses the artillery’s shock advantage; too fast, and he becomes victim to it.

Having received the order from I Corps forty-eight hours prior, 35th Division Headquarters issued orders to regimental commanders in the afternoon of September 24, 1918. In his Reminiscences of the 137th U. S. Infantry, Carl E. Haterius reproduces the 35th Division’s “Secret Field Orders,” which detail the attack plan (127-144).

The 35th Division would attack in “column of brigades,” meaning each of its two brigades would span the division sector, one behind the other. The 69th Brigade would lead; the 70th would follow in support.

Within brigades, regiments were to advance “side by side, each with one battalion in the first line, one in support, and one in reserve.” (128) Therefore, the division sector was divided in two. The 69th’s 138th Regiment, on the right, would take Vauquois Hill. On the left, the 137th, headquartered at Buzemont, would take the “V of Vauquois,” a formidable network of trenches, zig-zagging from the hill’s west flank to the village of Boureuilles a mile away.

The 137th Regiment’s twelve companies were divided into three battalions. First Battalion, Companies A through D, was assigned to the brigade reserve. Second Battalion, Companies E through H, would support Third Battalion—Companies I through M, which would lead.

From the field orders: “Parallel of departure for leading battalions—a line approximately 500 meters from the enemy’s front line trenches…” (139)

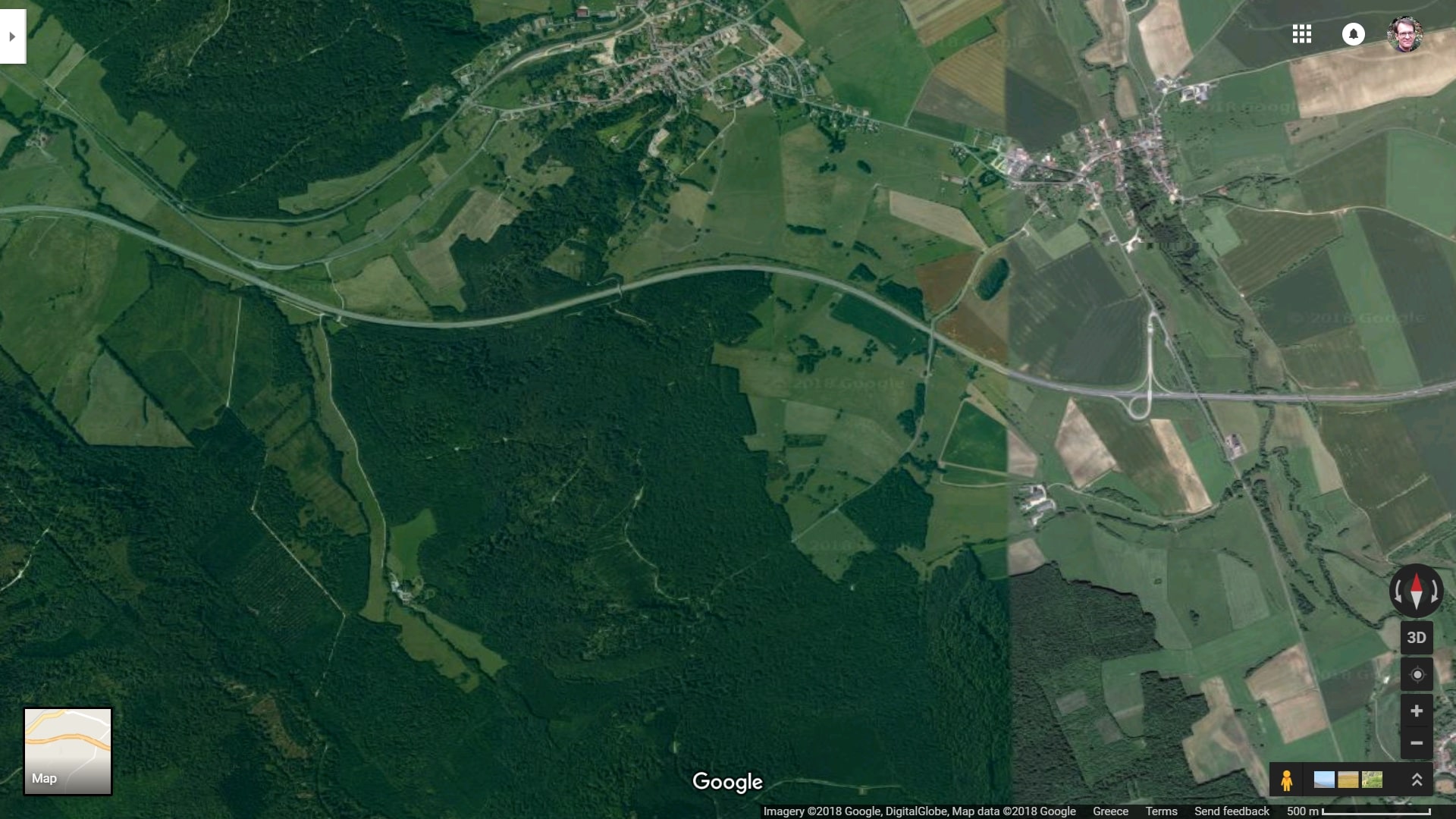

In the sector, the stretch of wounded earth between opposing trenches, called “No Man’s Land,” was approximately 500 meters wide. Private B. F. Potts and his comrades of Company M were on its edge.

My great grandfather, like many veterans, didn’t talk much about his wartime experience. His family has only his discharge paper and a few anecdotes.

One hundred years later, I’ve discovered a few documents that bear his name. From draft registration to discharge, I’m following the paper trail of B. F. Potts’s journey to the battlefields of the Great War in France and back home again.

Previous articles:

“Well, Daddy, what did you think about France?”

“It’s a very muddy place.”

Benjamin Franklin Potts Registers for the Draft

As the Great War thundered across the fields of northern France, ten million American men, ages 21 to 30, signed their names to register to be drafted into military service.

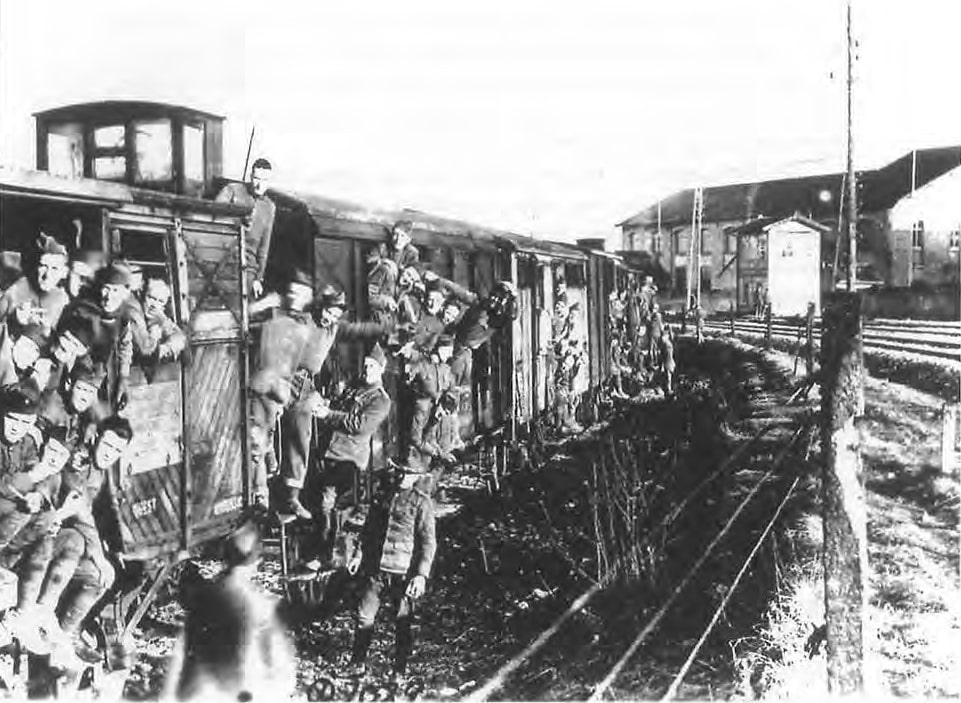

Military Induction and Entrainment

“I, Benjamin Franklin Potts, do solemnly swear to bear true allegiance to the United States of America, and to serve them honestly and faithfully, against all their enemies or opposers whatsoever…”

“If it moves, salute it. If it doesn’t move, paint it!”

Embarkation, the Tunisian, and the Bridge of Ships

In his first ocean voyage, B. F. Potts crossed the submarine invested waters of the North Atlantic in a convoy of steamers escorted by a warship.

Enterprise, Tennessee: The Town That Died

Grandpa owned matched pairs of horses. Him and the boys [Ben and his brothers] cut and snaked logs out of the wood to the roads. He got a dollar a day plus fifty cents for the horses.

Rendezvous with the 35th Infantry Division

“Some of the guys disobeyed orders, went into the town, broke into a bakery, and stole all the bread and baked goods…”

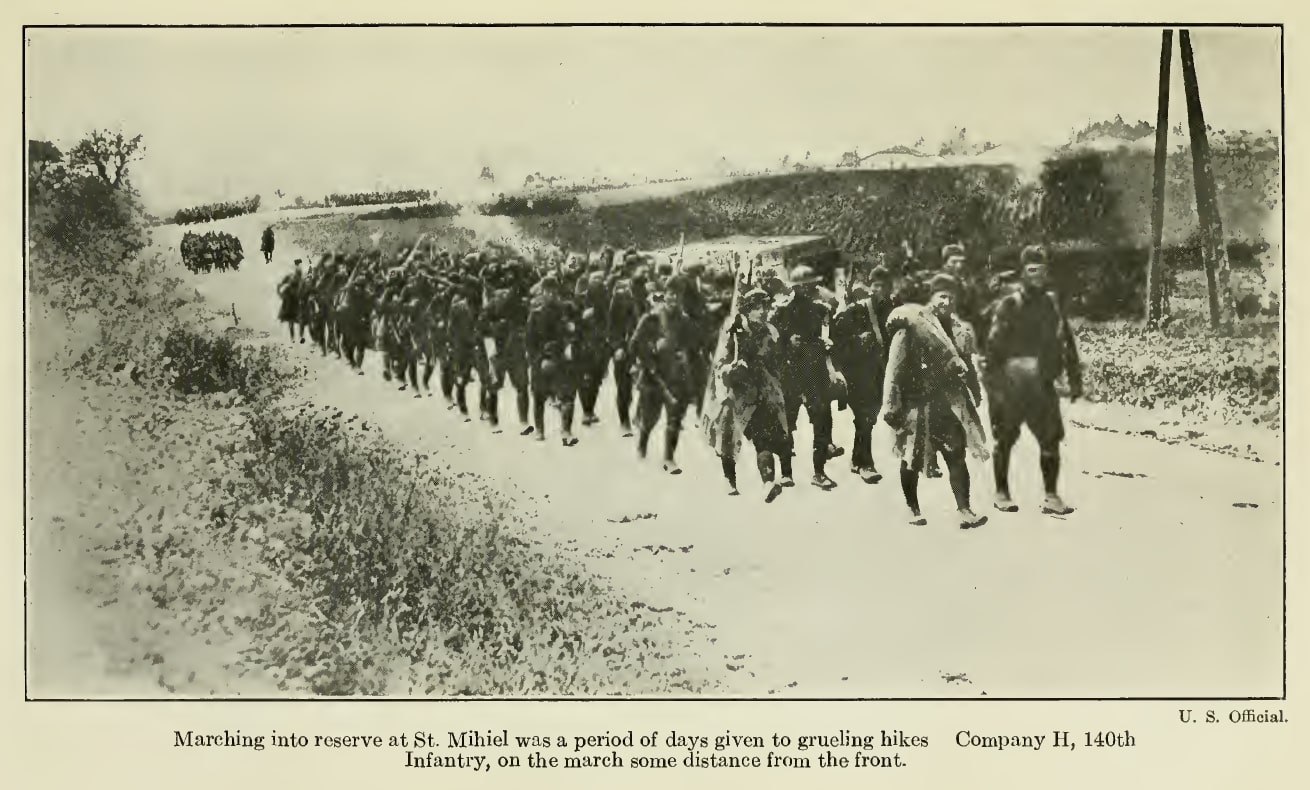

The battle of Saint-Mihiel (September 12-15) would be Pershing’s first operation as army commander. He assigned the 35th to the strategic reserve, whose purpose is to replace a weakened unit or to fill any gap in the line created by the enemy.

“Private Potts, how tall are you?”

The soldier, looking into a button of the captain’s coat, says, “Five foot three, sir.” The wide brim raises.

On the front now, the 35th was in range of artillery fire, and enemy planes made nighttime bombing raids over the countryside.

Next date:

September 25—Prelude to Battle

Reminiscences of the 137th U. S. Infantry Carl E. Haterius, Topeka, Kansas: Crane & Company, 1919