Embarkation, the Tunisian, and the Bridge of Ships

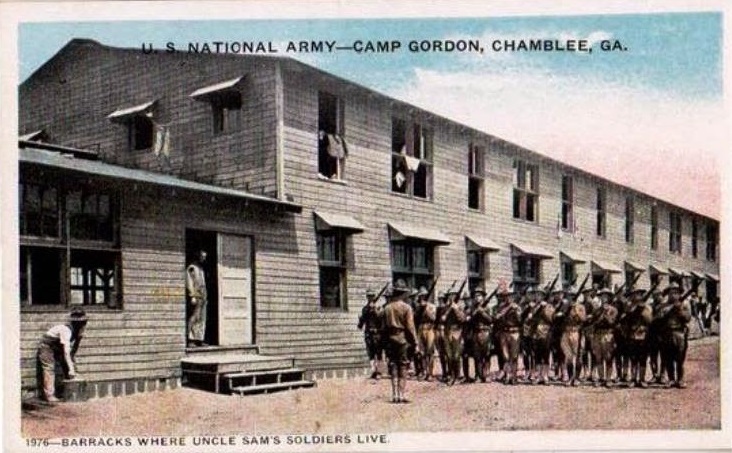

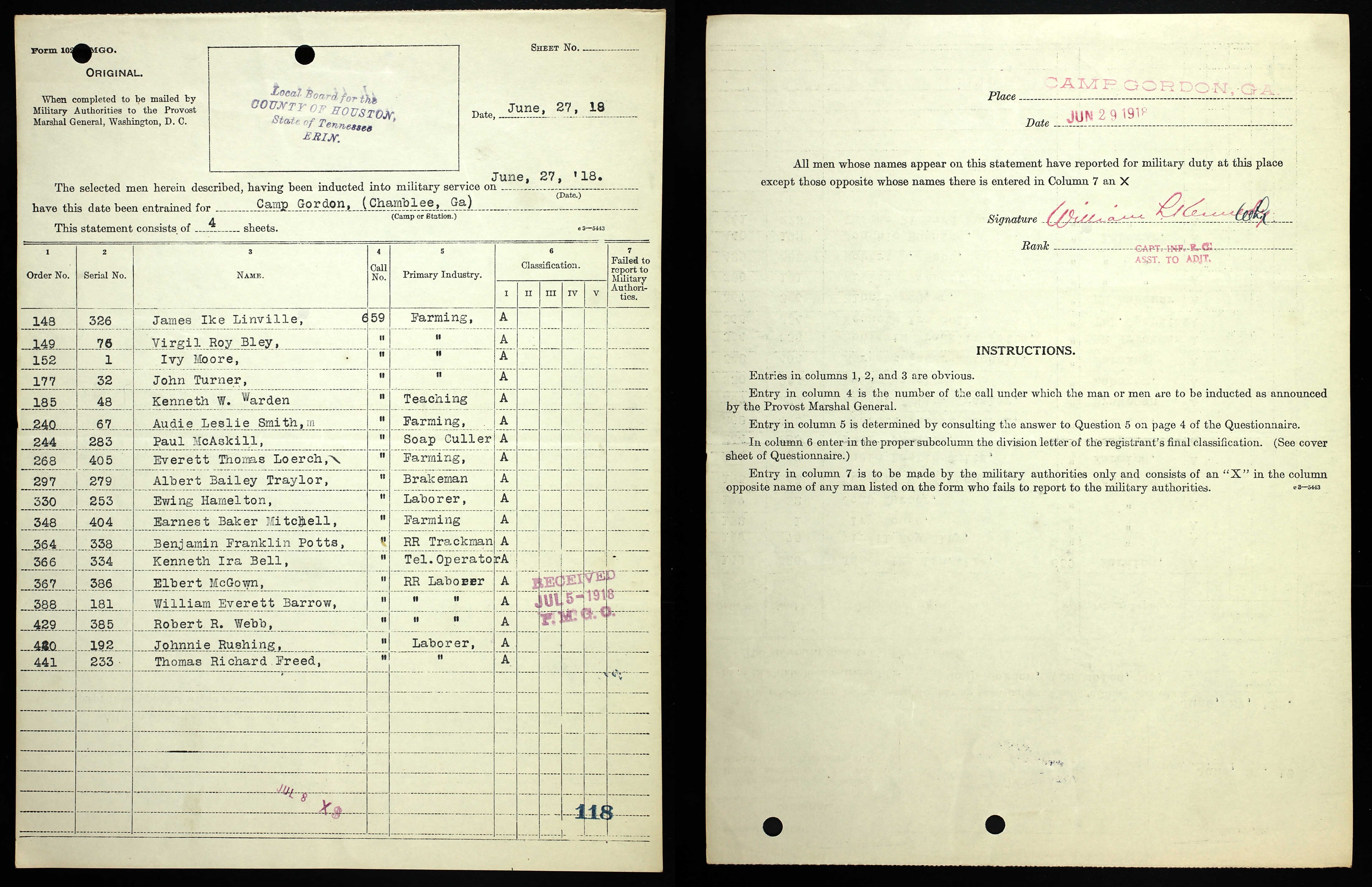

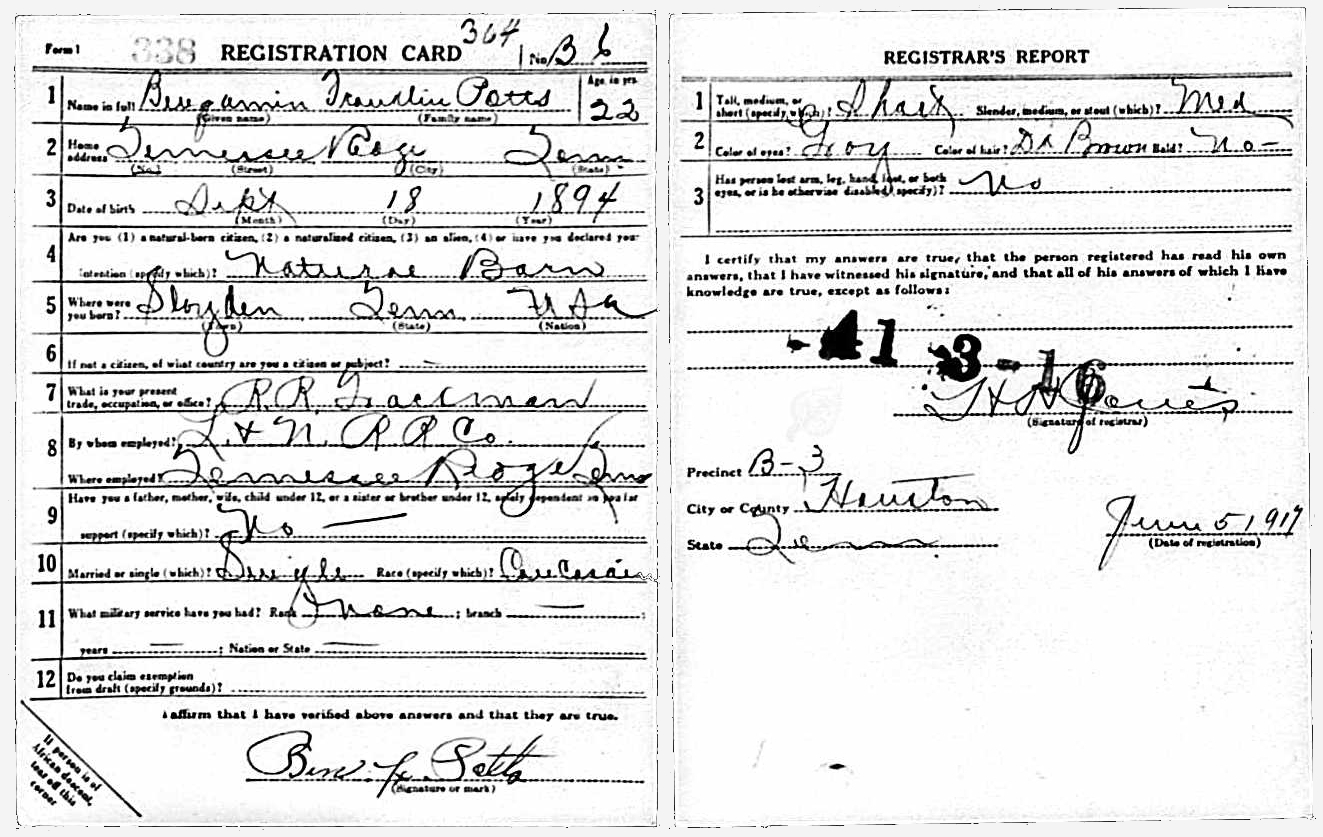

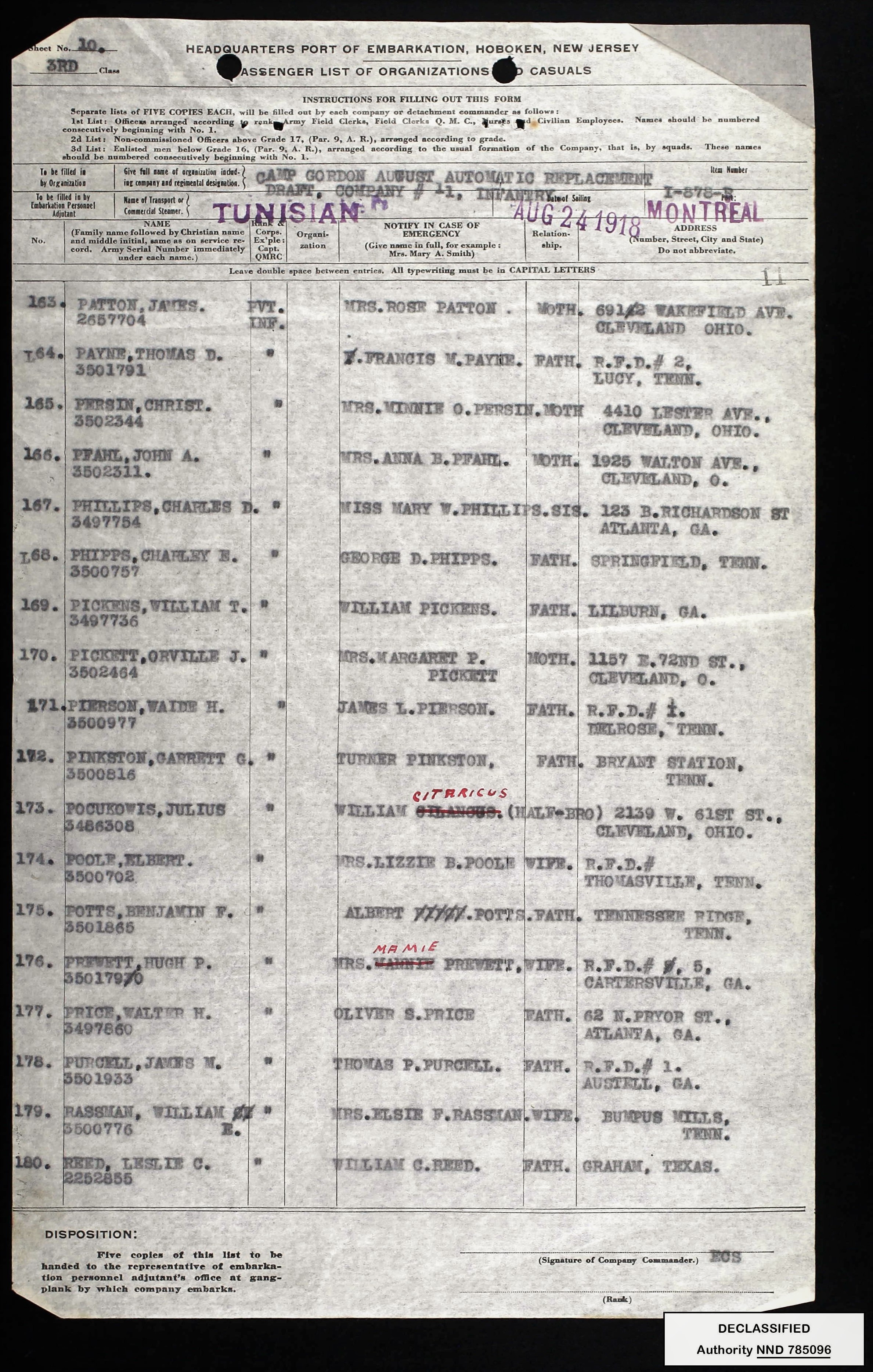

Potts, Benjamin F., PVT. INF., Army Serial Number 3501865, and other members of Camp Gordon August Automatic Replacement Draft Company #11, Infantry, boarded the Tunisian at Montreal on August 24, 1918, bound for Liverpool.

From the Tunisian’s Passenger List, August 24, 1918

From the Tunisian’s Passenger List, August 24, 1918

It was in the summer of 1918 that General Pershing, commander of the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF), promised the men that, by Christmas, they’d be in “Heaven, Hell, or Hoboken.”

As the Headquarters Port of Embarkation, Hoboken, New Jersey, was where many American troops shipped off to war, and as the port where they hoped afterward to return, it became a homecoming emblem. It was already a busy port before 1917, but when the army began to move men and equipment through it as well, the supporting rail system bogged down in gridlock. To relieve congestion, sub-ports were opened in the US at Boston, Baltimore, and Philadelphia and in Canada at Halifax, St. Johns, and Montreal.

To transport the two million soldiers that eventually made up the AEF in Europe along with the necessary equipment in a timely manner, war planners knew, would require a veritable “bridge of ships.” To that end, the US government ordered the construction of new ships, commandeered American cruise liners, borrowed ships from the British, and seized enemy vessels.

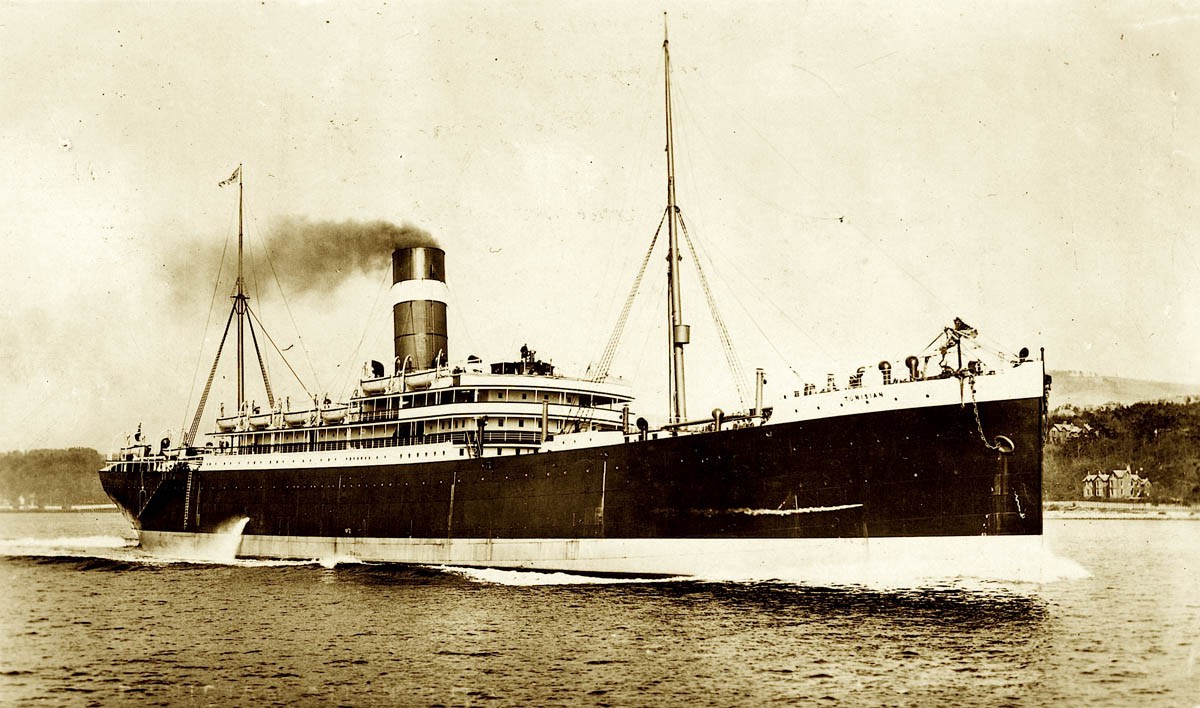

The Steamship Tunisian was built by Alexander Stephen & Sons for the Allan Line Steamship Company of Glasgow and launched at Princess Dock on the River Clyde, near Greenock, Scotland, January 17, 1900.

Tunisian on trials on the River Clyde, 1900

Tunisian on trials on the River Clyde, 1900

Five hundred feet (152 m) long with a 59-foot (18 m) beam (a ship’s widest point at the waterline), she could accommodate 1,460 civilian passengers on four decks. At a cruising speed of 14 knots, like most commercial steamers of the time, she could keep pace with contemporary warships.

In magazine advertisements during her commercial career, the Tunisian was described as a “Luxurious Cabin Steamer.” During the war, she served as a prisoner-of-war ship and a troop transport for Canadian and American forces.

Leaving London, August 7, 1918, she docked in Montreal August 19, disembarking 241 civilian passengers, listed as tourists. Five days later, she steamed down the Saint Lawrence carrying US troops.

In his first ocean voyage, B. F. Potts crossed the submarine invested waters of the North Atlantic in a convoy of steamers escorted by a warship. He passed the long summer days scrubbing the decks, responding to boat drills and fire drills, and trying not to be sick. At night, no lights and no smoking were allowed on deck. The crossing from Montreal to Liverpool would take about 11 days, during which a life vest, made of cork, was his constant companion.

After the war, the Tunisian continued her passenger route as part of the Canadian Pacific Line. She was converted from steam to oil fuel in 1921 and in 1922 renamed the Marburn. As the Marburn, she finished her career, scrapped at Genoa, in 1928.

My great grandfather, like many veterans, didn’t talk much about his wartime experience. His family has only his discharge paper and a few anecdotes.

One hundred years later, I’ve discovered a few documents that bear his name. From draft registration to discharge, I’m following the paper trail of B. F. Potts’ journey to the battlefields of the Great War in France and back home again.

Previous articles:

“Well, Daddy, what did you think about France?”

“It's a very muddy place.”

Benjamin Franklin Potts Registers for the Draft

As the Great War thundered across the fields of northern France, ten million American men, ages 21 to 30, signed their names to register to be drafted into military service.

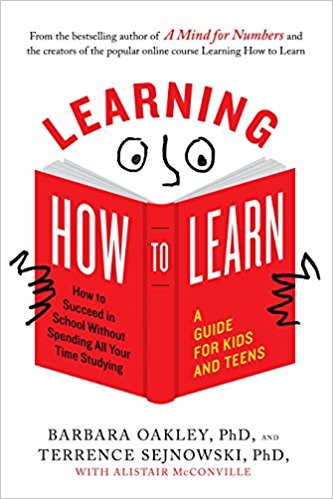

Military Induction and Entrainment

“I, Benjamin Franklin Potts, do solemnly swear to bear true allegiance to the United States of America, and to serve them honestly and faithfully, against all their enemies or opposers whatsoever…”

“If it moves, salute it. If it doesn’t move, paint it!”

Next date:

September 7—Rendezvous with the 35th Infantry Division

“Life at Sea,” Jay in the War, James Shetler

For more details about what Ben Potts’ first ocean voyage must have been like, I recommend this article by James Shetler, whose grandfather, Sergeant Jay Shetler, crossed the Atlantic aboard the steamship Katoomba one month before, also on his way to the Great War.

The Bridge to France, Edward N. Hurley

A book by the wartime Chairman of the United States Shipping Board

Sealift in World War I, GlobalSecurity.org

Trans-Atlantic Passenger Ships, Past and Present, Eugene W. Smith

In the index, look for Marburn (p. 343) and Tunisian (p. 349)

Oliver Rackham, 1939-2015

Oliver Rackham, 1939-2015 Zelkova abelicea, circa 1300-

Zelkova abelicea, circa 1300-