The confusion that began in the fog the morning before, continued through the morning of September 27. Around 3:00 a.m., the 137th Regiment, now behind the 139th, received orders to support the 139th in its morning attack, which was to begin at 8:30 after a three-hour artillery barrage. The 137th received a new order some while later, giving 5:30 as the hour of attack, after only a five-minute barrage. Around 5 a.m., a third order put H-hour at 6:30; the barrage to last one-hour.

The following cry might have been heard, bounding in the darkness between the slopes on either side of Buanthe Creek:

“Let him lie in an artillery shower all night, if you must. But do not disturb a soldier’s sleep, sir, with your orders that change from one minute to the next!”

Units had got mixed in the fog the first morning, and continued shelling prevented any reorganization. So at this point, Private Potts, whether a runner or not, could have been anywhere in the division sector. There are reported cases where an individual, a detachment, or an entire battalion went beyond the front line shown on the map.

However, not having any anecdotes from Grandpa Ben saying he had been too far forward, we’ll assume he was behind the limit of advance. In any case, when a unit of any size has lost contact with its parent unit, it fights with whatever higher command it encounters.

At 5:30, the men of the 137th heard rifle shots and the distinct sound of American machine guns. The noise came from the front but to their right, where the 140th Regiment had not received the third order. More worrying to their ears was what they didn’t hear. While the German artillery kept up through the night and now increased in intensity, their own artillery, which was to prepare the terrain for the attack, was silent.

Still no barrage at 6:30, the 137th prepared to move forward behind the 139th. They waited. Seven o’clock… enemy artillery increased to their fore. Finally, lieutenants and sergeants passed an order down the line: “Prepare to advance!”

“We’re ready, sir. Let us at those damn guns!”

Still they waited. Rain clouds gathered overhead.

This confusion of orders, which is, in fact, a failure of communication, is a typical battlefield scenario. In the modern military, men and officers alike use a special term for it: “cluster” in its short form. Although it’s outside the scope of this narrative, Kenamore, in four pages, recounts the episode from the brigade and division commanders’ perspective (148-151). It’s edifying.

Unknown to the troops lying in wait, the 139th’s regimental commander had sent a message by runner to the brigade at 6:30, saying he was ready to attack as soon as he had artillery. With no reply and no artillery at 7:00, the commander advanced the regiment anyway.

“His formation caught the full fire of the enemy artillery and machine guns. Ristine [139th commander] was able to advance, but as he saw the swaths the opposing fire was making in his ranks, he decided the price was too heavy. He halted his regiment, ordered the men to dig in, and sent a message to brigade headquarters that he could not advance further without artillery support.” (Kenamore 151)

Behind the 139th, the men of the 137th Regiment, indeed, the entire 35th Division waited, throughout the day, under clouds that threatened rain and a shower of enemy shells that threatened an end to their suffering.

Kenamore cites a message to the 35th Division commander, General Traub, from General Pershing:

“He expects the 35th Division to move forward. He is not satisfied with the Division being stopped by machine gun nests here and there. He expects the Division to move forward now in accordance with orders.” (154)

We might imagine the impact of the curt message on the division general, not from his corps commander but from the next higher—the army commander himself. The message, received at 4:30 p.m., lit a fire that spread through the chain of command.

“At 5:30 [p.m.] the division stood upon its feet amidst its dead, and prepared to advance, to show whether it was as good a fighting outfit as it believed it was.

“…the 139th came out of its foxholes like war dogs off the leash. They took a singeing fire full in the face, charged over the machine guns and stamped them out like nests of rats and, with the assistance of other units [the 138th and the 137th], had taken both Charpentry and Baulny before stopping to count the cost. The line they could not breach in the morning was no weaker. It did not crumble. But it was as if our men had gathered strength while waiting through the day, and in the afternoon the Germans could not stop them.” (Kenamore 155-156)

On the right, the 140th, supported by the 138th, also advanced at 5:30 p.m. Their gains, however, were not as great.

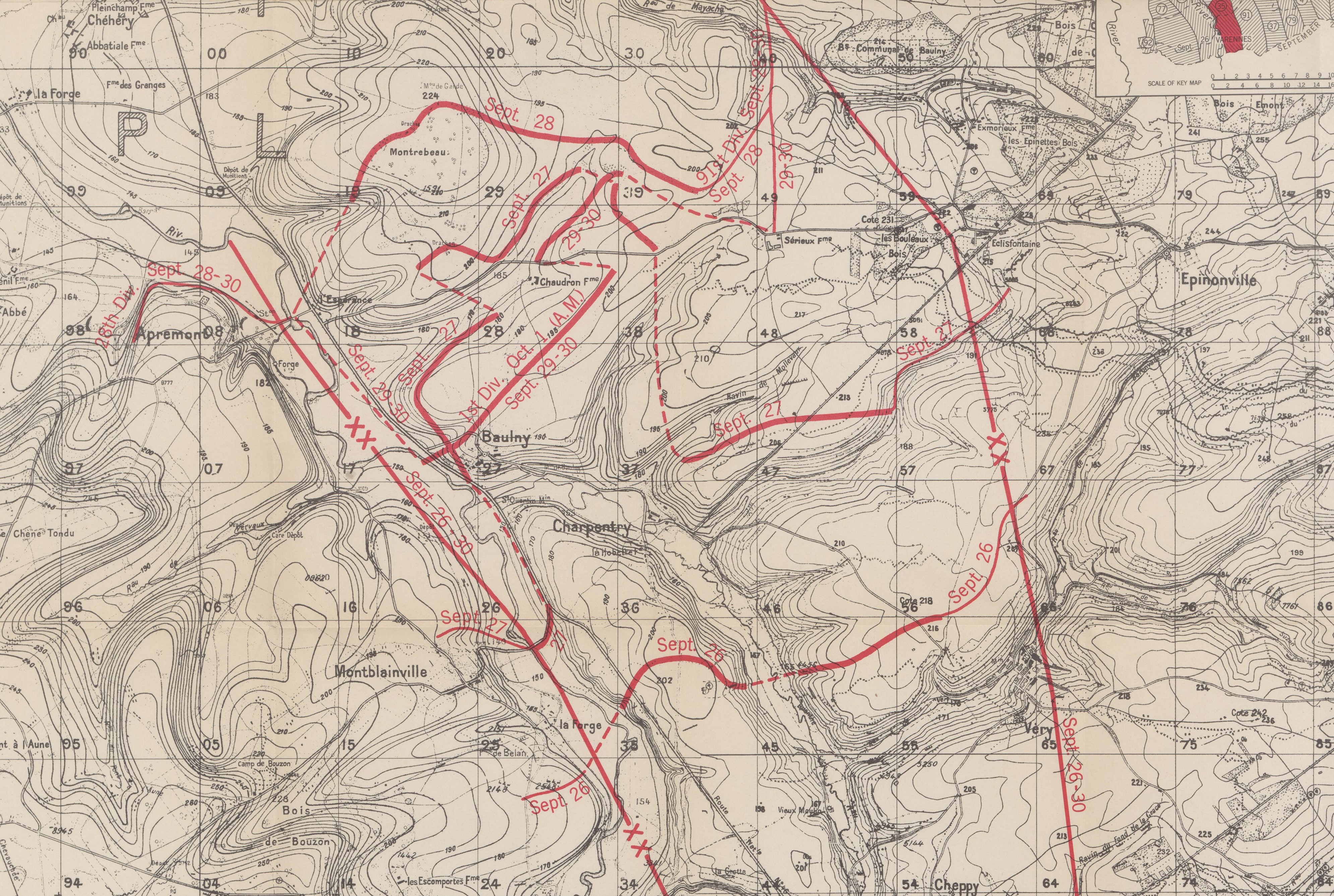

Mixed elements of the 139th and the 137th, including our Third Battalion, dug in after midnight. The lead element lay “in a little hallow” north of Baulny. (Kenamore 158) With the lagging 28th Division, on their left, and the 140th two kilometers behind, on their right, the 137th and 139th found themselves defending a salient.

Map section, September 27, 35th Division, Grange le Comte Sector, Meuse-Argonne, American Battle Monuments Commision 1937

Map section, September 27, 35th Division, Grange le Comte Sector, Meuse-Argonne, American Battle Monuments Commision 1937

The “little hallow” north of Baulny is at the limit of advance on the division’s left, below the red text “Sept. 27”

My great grandfather, like many veterans, didn’t talk much about his wartime experience. His family has only his discharge paper and a few anecdotes.

One hundred years later, I’ve discovered a few documents that bear his name. From draft registration to discharge, I’m following the paper trail of B. F. Potts’s journey to the battlefields of the Great War in France and back home again.

Previous articles:

“Well, Daddy, what did you think about France?”

“It’s a very muddy place.”

Benjamin Franklin Potts Registers for the Draft

As the Great War thundered across the fields of northern France, ten million American men, ages 21 to 30, signed their names to register to be drafted into military service.

Military Induction and Entrainment

“I, Benjamin Franklin Potts, do solemnly swear to bear true allegiance to the United States of America, and to serve them honestly and faithfully, against all their enemies or opposers whatsoever…”

“If it moves, salute it. If it doesn’t move, paint it!”

Embarkation, the Tunisian, and the Bridge of Ships

In his first ocean voyage, B. F. Potts crossed the submarine invested waters of the North Atlantic in a convoy of steamers escorted by a warship.

Enterprise, Tennessee: The Town That Died

Grandpa owned matched pairs of horses. Him and the boys [Ben and his brothers] cut and snaked logs out of the wood to the roads. He got a dollar a day plus fifty cents for the horses.

Rendezvous with the 35th Infantry Division

“Some of the guys disobeyed orders, went into the town, broke into a bakery, and stole all the bread and baked goods…”

The battle of Saint-Mihiel (September 12-15) would be Pershing’s first operation as army commander. He assigned the 35th to the strategic reserve, whose purpose is to replace a weakened unit or to fill any gap in the line created by the enemy.

“Private Potts, how tall are you?”

The soldier, looking into a button of the captain’s coat, says, “Five foot three, sir.” The wide brim raises.

On the front now, the 35th was in range of artillery fire, and enemy planes made nighttime bombing raids over the countryside.

Planning the Meuse-Argonne Offensive

On the left, the 137th would take the “V of Vauquois,” a formidable network of trenches, zig-zagging from the hill’s west flank to the village of Boureuilles, a mile away.

The gun jumps, the earth shudders, a shock wave shatters the air and accompanies a roar that bursts between the ears. Powder fumes permeate the air. Explosions count seconds across unending darkness.

…up until 7:40 a.m. when the rolling barrage ceased, we can follow Private Potts’s movement across the battlefield.

Scrawling in a notepad, the commander tears the sheet, folds it, and thrusts it into the runner’s hands.

“Potts, take this message to brigade. Tell them we need artillery now. Go!”

Next date:

September 28—Montrebeau Wood