Taking Vauquois

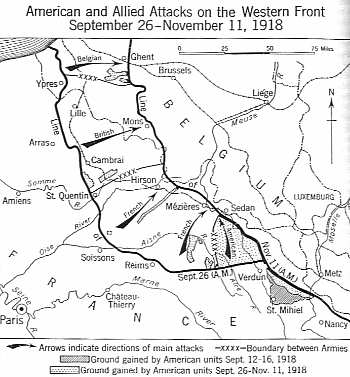

For the French, it’s the Battle of Verdun. For the British, the Somme. For the Americans, the Meuse-Argonne is the superlative battle. The largest battle in US history: 1.2 million American soldiers participated. The longest battle: lasting 47 days. The deadliest: 26,277 Americans killed.

The battle ended with the war, November 11, 1918. It began September 26. For the 137th Infantry Regiment, it began at the “V of Vauquois.” Private Potts, with Company M, was in the lead battalion.

Our battlefield journalists, Clair Kenamore and Carl Haterius, were there:

Kenamore: “At 5:30 a.m. [GMT+1] the infantry went over all along the line. There was no breakfast and little ceremony about it. The lieutenant or sergeant who was leading the platoon, when his watch told him the zero hour was but a few minutes off, would give the order: ‘Prepare to advance.’

“The men would crawl out of their foxholes, pick up their raincoats, look to their rifles, and wait. At ‘H’ hour the platoon leader would say: ‘All right, let’s go,’ and leading the way, he would set his face to the north and move out, his men following.” (90)

Haterius: “At 5:30 a.m. the signal hour broke, and as the barrage lifted, the commands were given, and the masses of olive drab forms, with helmets adjusted, gas masks in position, and rifle in hand, rose and scampered up over the top and started for the German positions across the way.” (145)

One century later, to the minute, we can place Private Benjamin Franklin Potts, with reasonable confidence, in the line between “Route Nationale No. 46” (left) and hilltop “253” (mid-sector), “approximately 500 meters from the enemy’s front line trenches…” (Haterius 139).

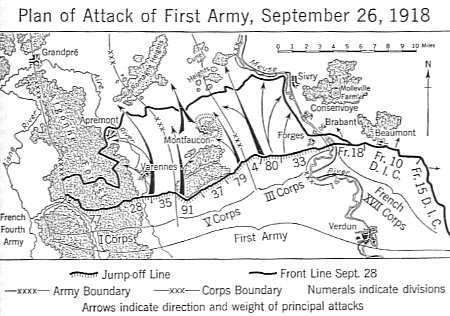

On this map, we can see where Private Potts would have been on any given day from September 26 through September 30, 1918.

On this map, we can see where Private Potts would have been on any given day from September 26 through September 30, 1918.

The map, prepared by the American Battle Monuments Commission in 1937, shows the area through which the 35th Division advanced in the first days of the Meuse-Argonne Offensive. The two red vertical lines mark the boundaries of the division sector, left and right. The ragged horizontal red lines show the front line at midnight on the date indicated.

From the battle plan, we know when the artillery’s rolling barrage began, as well as its rate of advance. We also know the infantry moved roughly 100 meters behind it. Therefore, up until 7:40 a.m. when the rolling barrage ceased, we can follow Private Potts’s movement across the battlefield.

At H-hour, the order is given: “Let’s go.” Private Potts crawls out of a shallow hole and heads into No Man’s Land. An exploding wall of dirt and debris, the artillery’s rolling barrage, precedes him. An orange flash, veiled by dense fog in the pre-dawn dark, reveals for an instant the man on his left and the man on his right and, to his front, grotesque forms in the disheveled land. The ground trembles. The blast pierces the ears. The soldier moves forward.

Haterius: “The effect of our six-hour barrage had been so thorough that the Boche front lines were pulverized beyond recognition. As the boys advanced, they found few if any Germans in the first line trenches; they had gone back into the second and reserve trenches. As the advance reached the second line trenches, the enemy commenced fire upon them, and soon a retaliatory fire of artillery, and machine-gun fire was in operation.” (145)

Private Potts’s first combat experience was here, west of Vauquois Hill, east of the town of Boureilles, at the “V of Vauquois.” Stretched across his path beyond the fog, four lines of trenches, named Balkans, Serpent, Constantinople, Enfer (pronounced on-fair).

Company M advances in staggered formation, never presenting a straight line shot of two men to the enemy trenches, with a few meters between each man, to minimize casualties from a single grenade or artillery blast. Ahead, in silhouette against the orange flashes, appears an earthen berm and mangled wire. Drawing no fire from the Balkans trench, the men pass cautiously.

Kenamore: “Once fairly in the field it became apparent that the going was to be very bad. The autumn frequently brings to that part of France a thick, clinging fog which only a bright sun or a strong wind can disperse. The heaviest fog of the season had descended on the valley of the Aire that morning. At first thought, it appeared that this might be of assistance to the Thirty-fifth, for it would conceal the advancing troops from the waiting machine gunners, but very soon it became apparent that the maintaining of liaison would be most difficult.

“Lieut. Bancon, flying over the sector, dropped a message at headquarters at 8:15 a.m., saying: “Impossible to find line. Our sector is a solid white snow-bank of clouds.” (91-92)

Any optimism rising in a soldier’s heart on passing the abandoned trench shatters in bursts of machine-gun fire from the next one. Platoon leaders shout orders, incoming artillery blasts the ground, dirt and mud rain down on the soldier, who moves forward in a crouch. Boom! A thrown grenade silences the machine gun. Rifles fire in the fog, Pop! Pop! Tat! Tat! Pop!

Serpent is littered with gray-clad bodies, still and bleeding. Through the trench the men must trudge. The stench of mud and blood and human waste assails the nose. Up the other side, the soldiers look to their left and right. Comrades in the fog, still thick, dull gray before dawn.

The blasts of the rolling barrage more distant, the order cuts through the mist, and Company M advances the line into the next burst of machine-gun fire. Adrenaline pumps in the veins. Legs move without thought. Tat! Tat! Pop! Boom!

Constantinople is cleared. Wounds are dressed. Prisoners escorted to the rear. The dead are marked with a rifle, fixed bayonet thrust in the ground; regimental band members bearing stretchers are to follow. Again the order, again the men advance.

By the time they cleared the last machine gun from their sector of Enfer (French for “Hell”), the boys of Company M were combat veterans, and the sun had not yet risen over the blanket of fog that covered the battlefield on that first of what would be five days of fighting.

Passing Enfer, Kenamore writes, “The leading battalion pressed forward, cleaned out the Aden strongpoint [“Ouvr. d’Aden” (illegible) on the map, south-east of Varennes in square 42], and in the hopeless fog, and with artillery fire which they had met from the first were stopped before the well constructed defenses of Varennes. Many machine guns opened, and there was no chance to look ahead into the gloom.” (127)

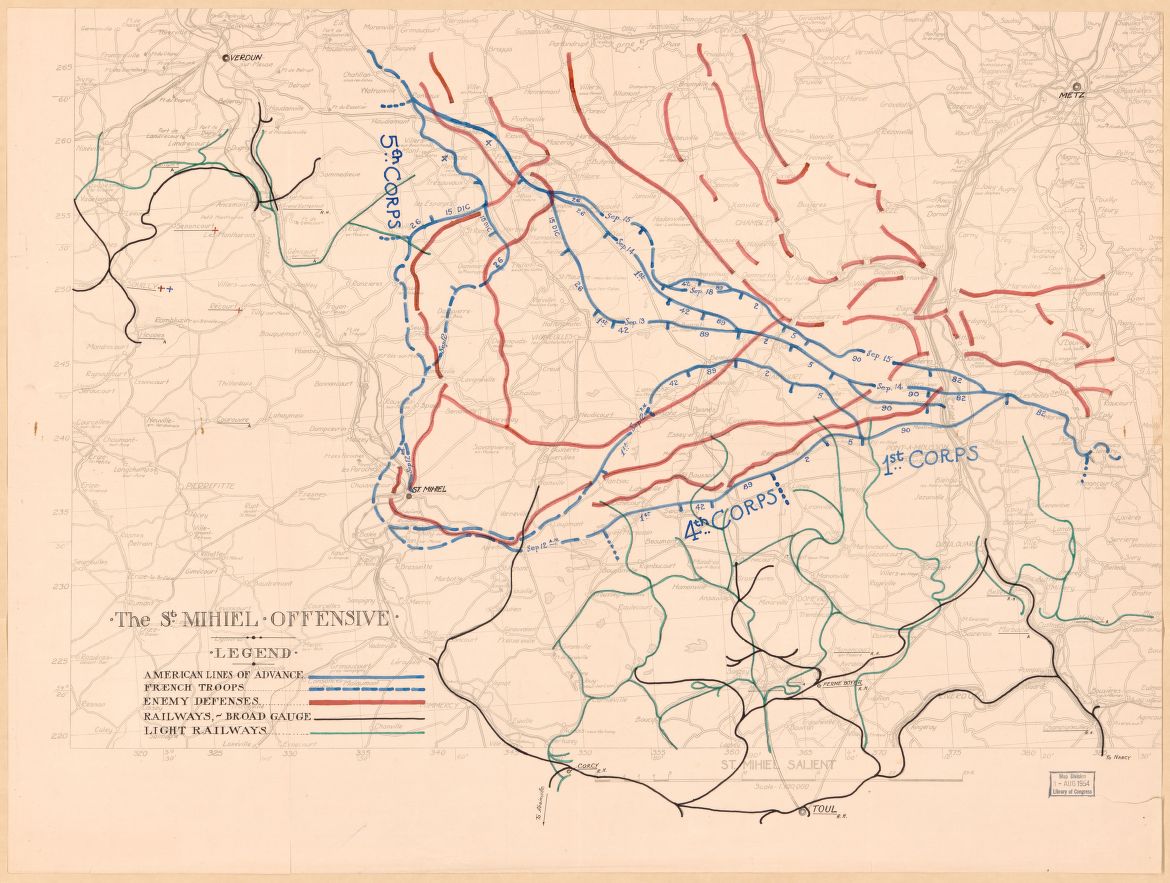

Meanwhile, on the right half of the division sector, the 138th Regiment, according to orders, avoided Vauquois Hill, moving around its east flank. This was done to prevent delay in the advancing line. The task of taking the fortified hill and Rossignol Wood behind it was assigned to a battalion of the support regiment.

As our Third Battalion, 137th Regiment, cleared the trenches of the “V of Vauquois,” the Second Battalion of the 139th Regiment, followed close behind. This battalion, once the leading elements had passed Vauquois Hill, veered to the right behind it to attack from the flank.

Kenamore: “Never before or afterward did the 35th find a place better defended than Vauquois. It was the result of four years intensive work by the Germans.” (94)

“A high French officer told me their losses there probably totaled 40,000. It was known to be thoroughly mined, to have excavations and tunnels of great length for quick communication and transferal of troops from one point to another.” (79)

Whether it was the lengthy bombardment prior to attack, the threat of being surrounded, the hill’s reduced strategic importance since the introduction of the airplane, or a combination thereof, when Second Battalion arrived, the Butte of Vauquois was scarcely defended.

Kenamore describes the action in a broad stroke: “…[Second Battalion] had methodically cleaned [the dugouts of Vauquois] of all enemy elements, killing or capturing all defenders.” 128

Hoyt gives more detail: “[Second Battalion] had found Vauqois (sic) Hill and Bois de Rossignol comparatively easy to handle. In some of the dugouts the moppers-up had found Germans, none of which had shown much fight. They had bombed and cleaned them out as they went along, endeavoring to overlook as few as possible in the fog of impenetrable thickness.” (74)

The 139th’s Second Battalion rejoined its regiment at 9:30 a.m. south of Verennes. The four-year Battle of Vauquois was over.

Battle of Vauquois, September 3, 1914 – September 26, 1918

Battle of Vauquois, September 3, 1914 – September 26, 1918

Summit of the Butte of Vauquois, showing German trenches (foreground), mine craters (middleground), and the French monument to the combatants and the dead of Vauquois (background)

My great grandfather, like many veterans, didn’t talk much about his wartime experience. His family has only his discharge paper and a few anecdotes.

One hundred years later, I’ve discovered a few documents that bear his name. From draft registration to discharge, I’m following the paper trail of B. F. Potts’s journey to the battlefields of the Great War in France and back home again.

Previous articles:

“Well, Daddy, what did you think about France?”

“It’s a very muddy place.”

Benjamin Franklin Potts Registers for the Draft

As the Great War thundered across the fields of northern France, ten million American men, ages 21 to 30, signed their names to register to be drafted into military service.

Military Induction and Entrainment

“I, Benjamin Franklin Potts, do solemnly swear to bear true allegiance to the United States of America, and to serve them honestly and faithfully, against all their enemies or opposers whatsoever…”

“If it moves, salute it. If it doesn’t move, paint it!”

Embarkation, the Tunisian, and the Bridge of Ships

In his first ocean voyage, B. F. Potts crossed the submarine invested waters of the North Atlantic in a convoy of steamers escorted by a warship.

Enterprise, Tennessee: The Town That Died

Grandpa owned matched pairs of horses. Him and the boys [Ben and his brothers] cut and snaked logs out of the wood to the roads. He got a dollar a day plus fifty cents for the horses.

Rendezvous with the 35th Infantry Division

“Some of the guys disobeyed orders, went into the town, broke into a bakery, and stole all the bread and baked goods…”

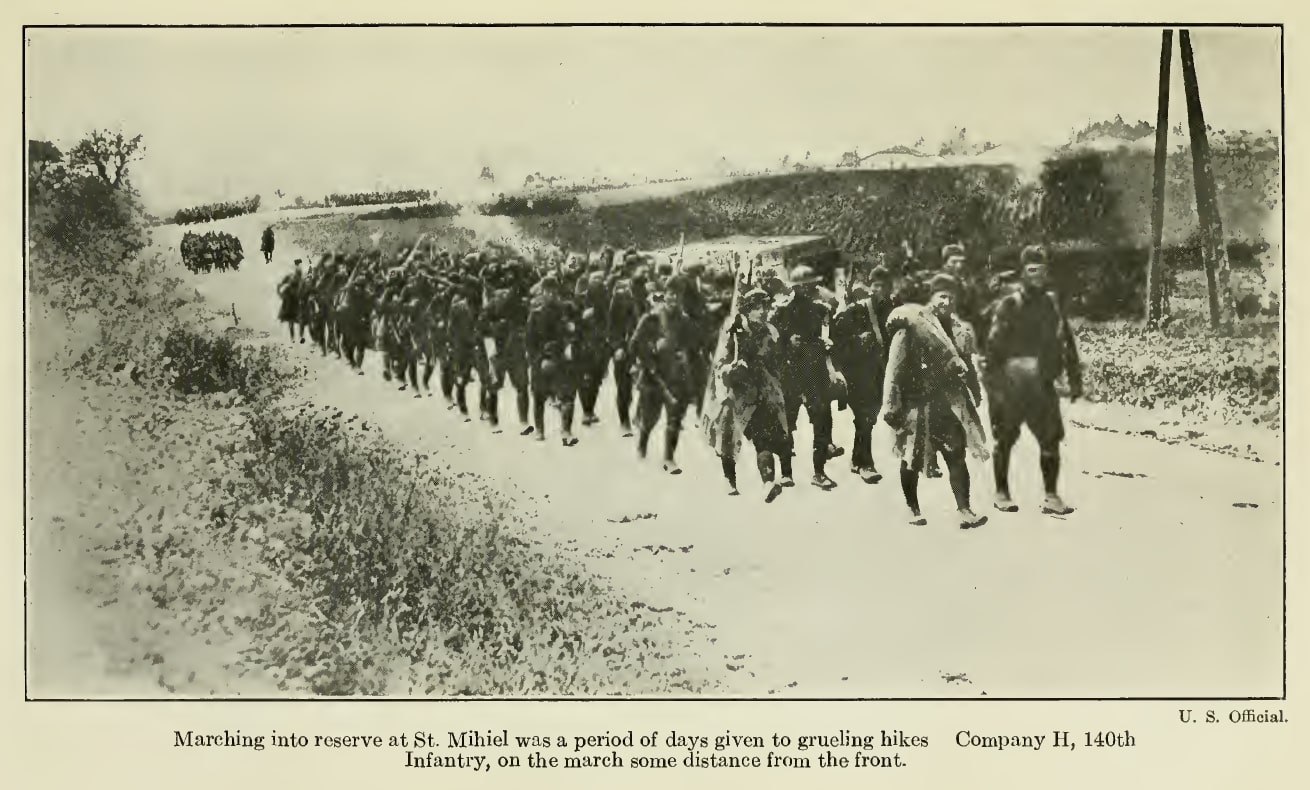

The battle of Saint-Mihiel (September 12-15) would be Pershing’s first operation as army commander. He assigned the 35th to the strategic reserve, whose purpose is to replace a weakened unit or to fill any gap in the line created by the enemy.

“Private Potts, how tall are you?”

The soldier, looking into a button of the captain’s coat, says, “Five foot three, sir.” The wide brim raises.

On the front now, the 35th was in range of artillery fire, and enemy planes made nighttime bombing raids over the countryside.

Planning the Meuse-Argonne Offensive

On the left, the 137th would take the “V of Vauquois,” a formidable network of trenches, zig-zagging from the hill’s west flank to the village of Boureuilles, a mile away.

The gun jumps, the earth shudders, a shock wave shatters the air and accompanies a roar that bursts between the ears. Powder fumes permeate the air. Explosions count seconds across unending darkness.

Next date:

September 26—The Fog of War