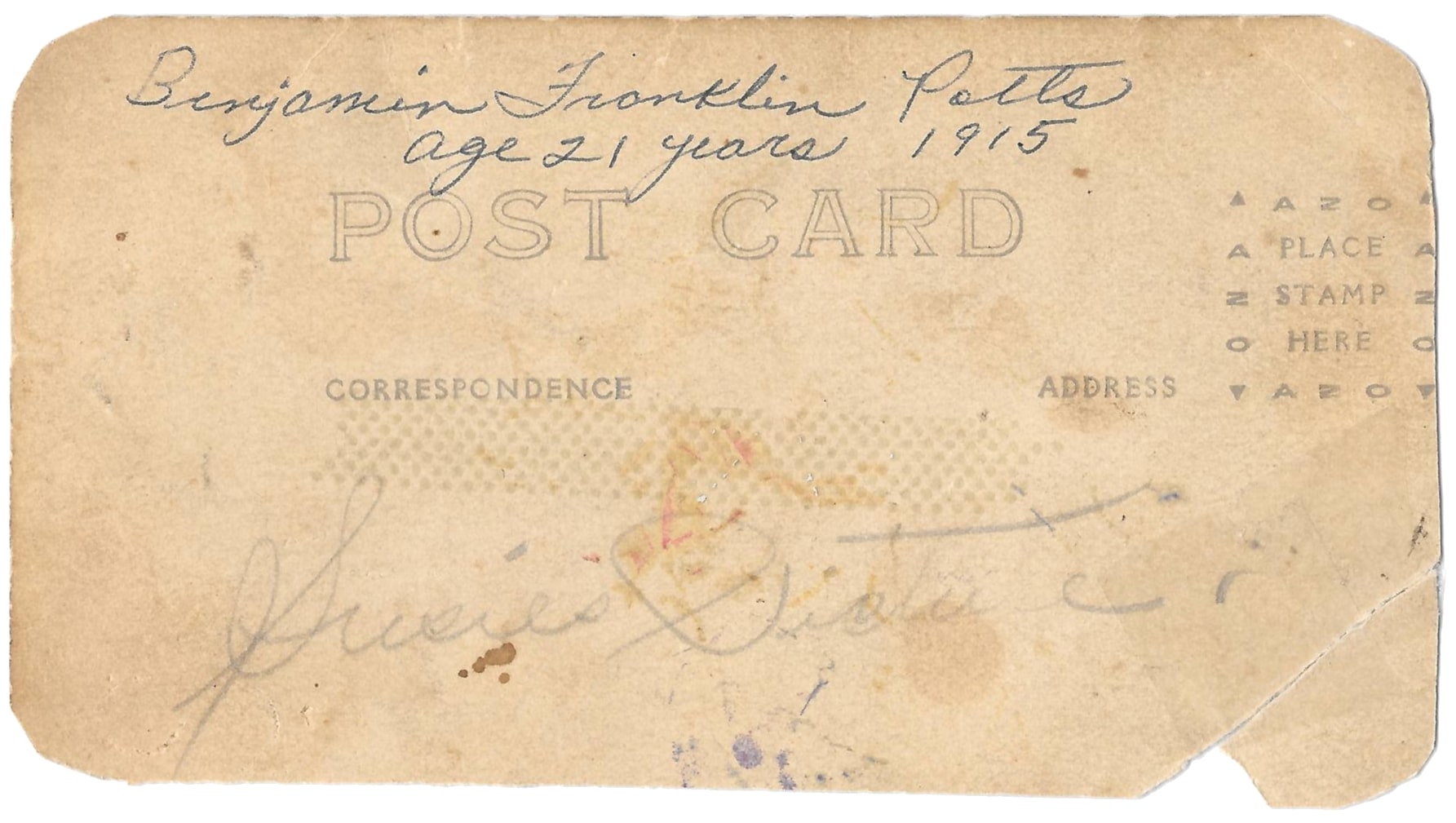

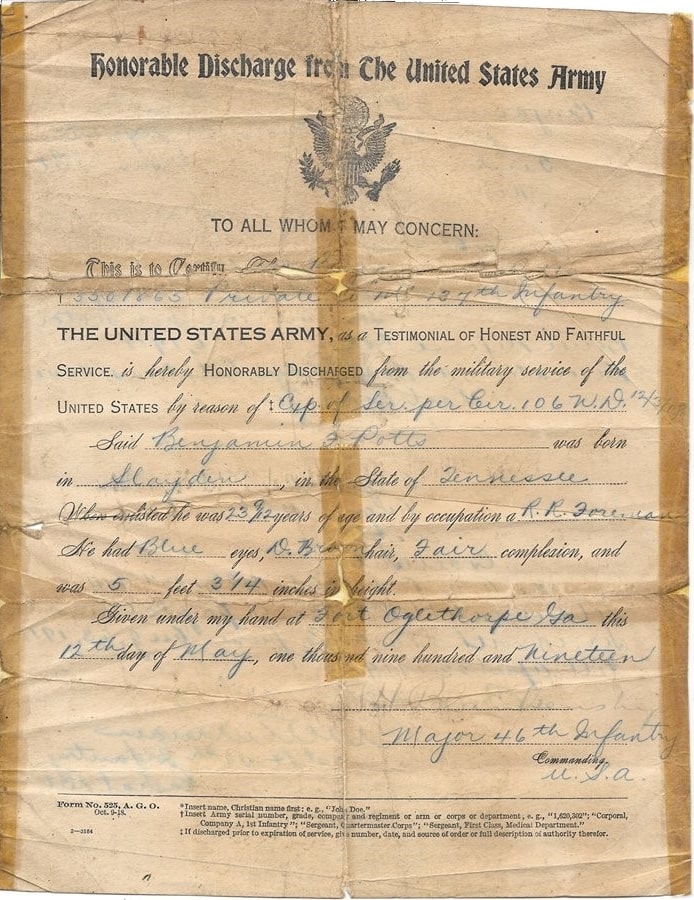

Included here are Benjamin F. Potts’s discharge and enlistment record, two sides of the same paper, accompanied by a transcript, including that of stamps and pencil marks on the latter.

Based on the penmanship (in which I am no expert), the lieutenant, signatory of the enlistment record, seems to be the scribe.

In the transcript, handwritten text is shown in italics. Where the original is illegible, I have compared with other handwritten text in the document and with similar records to derive a probable text, which I enclose in brackets. Where this is impossible, I leave an ellipsis between brackets.

The following information about the form is given in the footer margins:

Form No. 525. A. G. O. [Adjutant General’s Office]

Oct. 9-18.

3—3164

Asterisks (*), daggers (†), and double daggers (‡) indicate footer notes on either side of the form. Bracketed numbers mark my own notes.

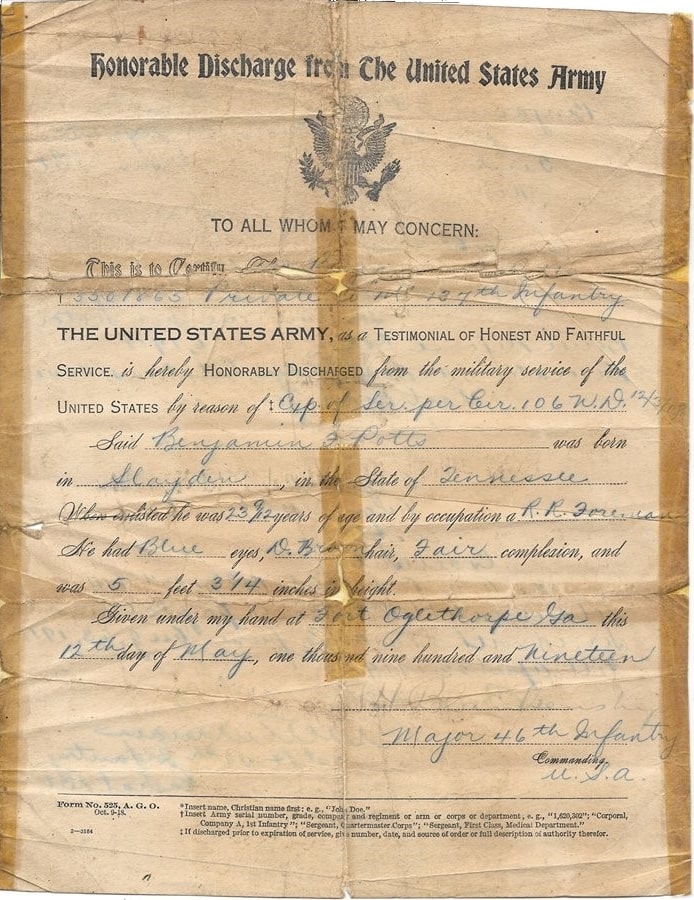

Honorable Discharge from The United States Army

TO ALL WHOM [IT] MAY CONCERN:

This is to Certify, [That* Benjamin F. Potts]

† 3501865[1] Private Co “M” 137th Infantry

THE UNITED STATES ARMY, as a Testimonial of Honest and Faithful Service is hereby Honorably Discharged from the military service of the United States by reason of‡ Exp. Of Ser. Per Cir. 106 W. D. 12/3/18[2]

Said Benjamin F. Potts was born in Slayden, in the State of Tennessee.

When enlisted he was 23 9/12 years of age and by occupation a R. R. Foreman.[3]

He had Blue eyes, D. Brown hair, Fair complexion, and was 5 feet 3 1/4 inches in height.

Given under my hand at Fort Oglethorpe, Ga this 12th day of May, one thousand nine hundred and nineteen.

[G. H. Blankenship][4]

Major 46th Infantry

Commanding

U. S. A.

* Insert name, Christian name first: e.g., “John Doe.”

† Insert Army serial number, grade, company and regiment or arm or corps or department, e.g., “1,620,302”; “Corporal, Company A, 1st Infantry”; “Sergeant, Quartermaster Corps”; “Sergeant, First Class, Medical Department.”

‡ If discharged prior to expiration of service, give number, date, and source of order or full description of authority therefor.

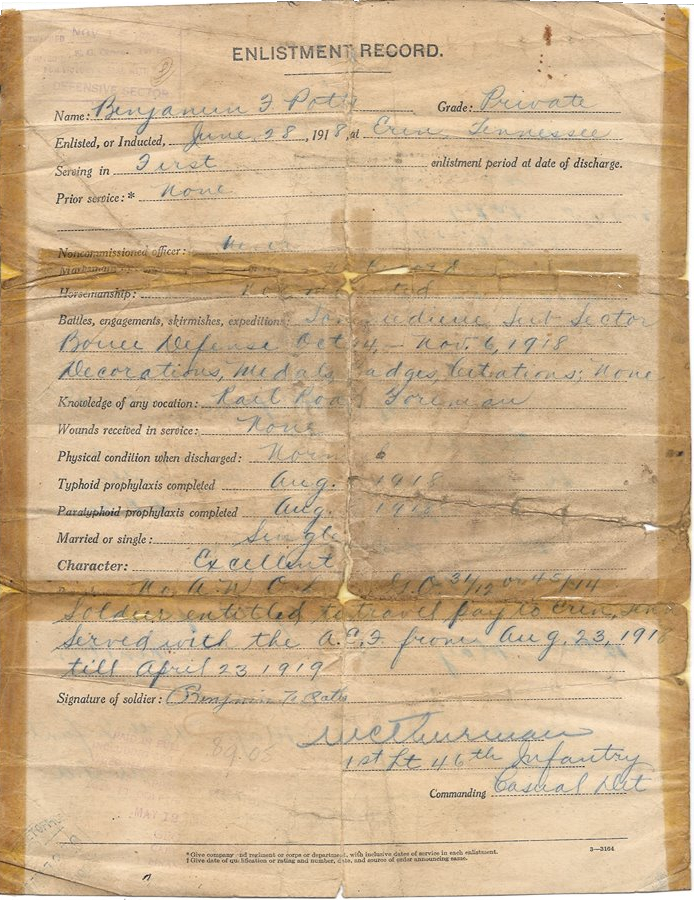

ENLISTMENT RECORD

Name: Benjamin F. Potts Grade: Private

Enlisted, or Inducted, June 28, 1918, at Erin, Tennessee

Serving in First enlistment period at date of discharge.

Prior service: * None

Noncommissioned officer: [Never]

[Marksmanship, gunner qualification or rating: † None of record]

Horsemanship: [Not mounted]

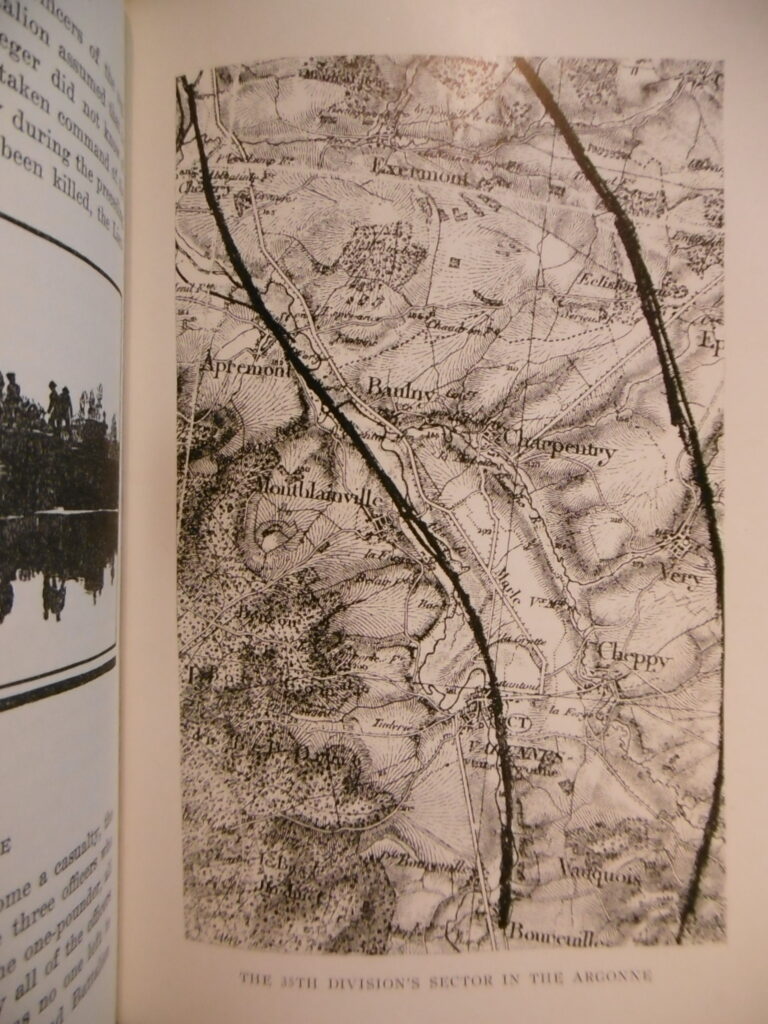

Battles, engagements, skirmishes, expeditions: Sommedieue Sub-Sector Bouee Defense Oct. 14 – Nov. 6, 1918[5]

Decorations, Medals, Badges, Citations; None

Knowledge of any vocation: Rail Road Foreman

Wounds received in service: None

Physical condition when discharged: Normal

Typhoid prophylaxis completed: Aug. […] 1918

Paratyphoid prophylaxis completed: Aug. […] 1918

Married or single: Single

Character: Excellent[6]

[Remarks:] No A. W. O. L. [under] G. O. 31/12 or 45/14[7]

Soldier entitled to travel pay to Erin, Tenn.[8]

Served with the A. E. F. from Aug. 23, 1918 till April 23, 1919

Signature of soldier: Benjamin F. Potts

[W. C.] Thurman

1st Lt 46th Infantry

Commanding Casual Det[9]

* Give company and regiment or department, with inclusive dates of service in each enlistment.

† Give date of qualification or rating and number, date, and source of order announcing same.

On the enlistment record, lower left corner, are faded stamps in red and blue and a number in pencil. The red stamp, shown first, may well be three separate stamps, separated in the transcript by em dashes.

Stamp in red ink:

PAID IN FULL 89.05[10]

INCLUDING $60 BONUS

[PRO]VIDED IN SEC 140[6 REVENUE ACT]

OF 1918 APPROVED [FEB 24TH]

1919.[11] FT OGLETHORPE

—

MAY 12 1919

—

GEO. [H. CHASE]

CAPT [Q. M. C.][12]

FINANCE [OFFICER]

Stamp in blue ink:

TICKET OFFICE

MAY 13 19

CHATTANOOGA[13]

__________

[1] The numeral 1 here could be a 7. Other documents, like the Tunisian’s passenger list, show a 1.

[2] Expiration of Service per Circular 106 War Department, December 3, 1918. Circular 106 stipulates that a soldier must be discharged from the Army post closest to home.

[3] During his service, B. F. Potts was not promoted in military rank. He was, however, promoted from railroad trackman at induction to foreman.

[4] I made out some letters and guessed the rest. An Internet search reveals a Major G. H. Blankenship of the 46th Infantry signed other discharges at Fort Oglethorpe.

[5] No mention of the Argonne battle. See forthcoming article, Friday.

[6] Other discharge papers imply the Army honorably discharged only persons of “excellent” character.

[7] No Absence Without Leave under General Orders No. 31, War Department, 1912, or No. 45, War Department, 1914.

[8] The Army paid five cents per mile. The distance was near 200 miles, which would be $10.00.

[9] Casual Detachment. A “casual” is a soldier not assigned to a unit.

[10] The penciled number is a dollar amount. A private earned $30 per month. A prorated portion, $12, plus the $60 bonus, from $89.05, leaves $17.05. The army paid five cents a mile, which makes 341 miles, the distance from Chattanooga through Nashville to McKenzie, TN, on the Nashville, Chattanooga & St. Louis Railway, then to Erin on the Louisville & Nashville.

[11] Within days of the Armistice, the US Congress adopted Section 1406 as an amendment to the year’s revenue act, which was approved in 1919.

[12] Quarter Master Corps

[13] Boarding the train at Chattanooga’s Terminal Station, outside of Fort Oglethorpe, Ben Potts was already in his home state.

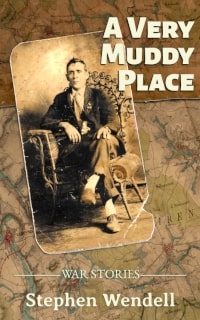

A Very Muddy Place

WAR STORIES

An intimate account of a soldier’s experience in World War I, A Very Muddy Place takes us on a journey from a young man’s rural American hometown onto one of the great battlefields of France. We follow Private B. F. Potts with the 137th US Infantry Regiment through the first days of the Meuse-Argonne Offensive. We discover a personal story—touching, emotional, unforgettable.

In 1918, twenty-three-year-old Bennie Potts was drafted into the US Army to fight in the World War. He served with the American Expeditionary Force in France. At home after the war, he married and raised a family, and the war for his children and grandchildren became the anecdotes he told them.

A century later, a great grandson brings together his ancestor’s war stories and the historical record to follow Private Benjamin Franklin Potts from Tennessee to the Great War in France and back home again.

Available in hardcover, paperback, and e-book.

More about A Very Muddy Place…

Disclosure: This page and linked pages contain affiliate links to Bookshop, Amazon, Apple, Barnes & Noble, and Kobo. As an affiliate of those retailers, Stephen earns a commission when you click through and make a purchase. Thank you for your support.

At Triopetra on Crete’s south coast, I learned that its highest rock is the place from which Icarus took off on his mortal flight, too close to the sun. I also learned that, while Icarus fell into the sea, his father and wing maker, Daedalus, flew on to Sicily…

At Triopetra on Crete’s south coast, I learned that its highest rock is the place from which Icarus took off on his mortal flight, too close to the sun. I also learned that, while Icarus fell into the sea, his father and wing maker, Daedalus, flew on to Sicily…