“Many when they come to die have spent all the truth that was in them, and enter the next world as paupers. I have saved up enough to make an astonishment there.” — Mark Twain

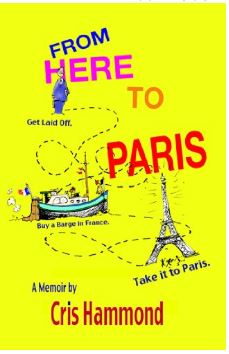

The Phaedra moored on stakes along the Burgundy Canal (photo by Cris Hammond)

The Phaedra moored on stakes along the Burgundy Canal (photo by Cris Hammond)

The Phaedra is a flat-bottom barge, 56 feet long and not twice as wide as my outstretched arms. Originally a commercial craft, she was put to service in 1925, hauling milk and cheese along the waterways between Holland and Belgium. At the time, a barge was pulled by men or horse along canals. For river navigation, she was built with a single mast. Made obsolete by a combustible engine, the mast now lies fixed over the main cabin.

I asked Cris what happened to the Phaedra during the war. He said none of his papers about the boat give any clue and suggested I make something up. So let’s imagine for a moment…

During World War II the Phaedra was requisitioned by the German army to ferry troop supplies from the Netherlands, through Belgium and into occupied France. Unknown to the Germans, the Dutch bargeman, whose name was Raemaekers, also carried coded messages between French resistance fighters and spies in Holland, who transmitted the messages to General de Gaulle in London.

Raemaekers almost got caught in early June, 1944. At Charleville, a port town on the Meuse, northern France, a German officer stumbled onto the scene during the message exchange. The bargeman fled on foot with the resistance operative, a French woman he called Angelica. Taken in by an old spinster and hidden in the cellar, the two spent a torrid night in each other’s arms.

The following day news of the Normandy invasion caused mayhem in the town. That night, Raemaekers slipped aboard the Phaedra and, learning that the Germans had blocked downstream traffic to allow shipments to the front, he made his escape south, up river. Angelica, continuing the mission, took the message north.

For months, Raemaekers navigated rivers and canals through occupied territory. He made it as far as Saint-Jean-de-Losne (pronounced /lohn/), at the end of the Burgundy Canal. As he pulled the Phaedra through the last lock into the Saône River, a series of three explosions cracked the air. The German army had blown up the bridge over the river to cover their retreat ahead of advancing Allied troops from the south.

Though he tried to track her down after the war, Raemaekers never saw Angelica again.

The entire story is documented in a book called The Phaedra Adventure, and none of this is true.

It is true, however, that the Phaedra was converted to a pleasure barge in the late 1940s. The cargo hold became a small apartment, complete with kitchenette, living area, two staterooms, two toilets and a shower. Also installed at this time, a pair of stained glass windows filter outside light from the pilothouse into the living area.

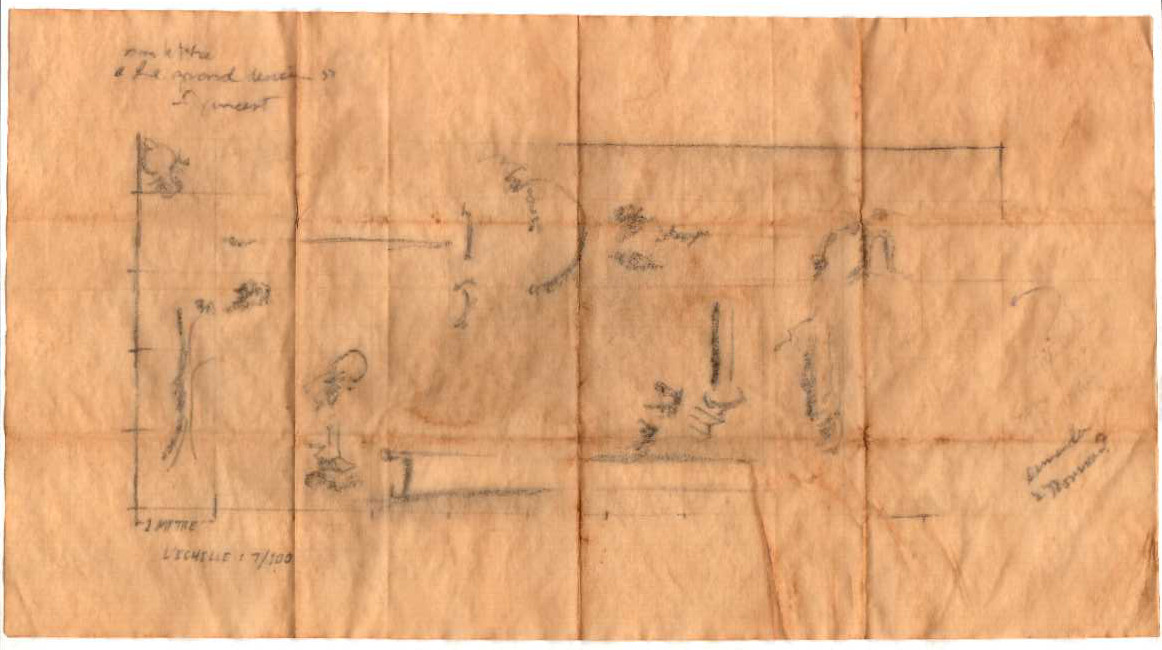

Amphitrite (left) and Poseidon in stained glass

Amphitrite (left) and Poseidon in stained glass

The windows depict Poseidon and Amphitrite, god and goddess of the sea. In Greek mythology, Phaedra is the daughter of Minos, first king of Crete, and Pasiphaë, who also gave birth to the Minotaur. The father of Minos was Zeus, brother of Poseidon. So the stained glass god and goddess are great uncle and aunt to Phaedra, and her half-brother is the Minotaur.

Before Cris, the Phaedra’s owner was a doctor and master woodcarver, who bought the barge in the 80s. In addition to fitting a new engine, he carved nautical and floral motifs in the wood trim, including the wheel pedestal.

Cris became the proud new owner in 2001 at Saint-Jean-de-Losne. He painted her in greens and blues. It’s a lovely palette for a barge that is today a veritable work of art. I’ve seen tourists strolling along the quay stop to take photographs and selfies with the Phaedra.

Between Poseidon and Amphitrite hangs a brass plaque with an inscription in Dutch: “BY BRAND DEZE PLAAT OMDRAAIEN”

Thinking it must be a motto, I asked Cris what it meant. He said, “Reverse this plaque in case of fire…”

The terror wight is acutely aware that the late release of The First Story pushes back the next one. Roy says he’s going to autograph covers of Littlelot and the Real Monster and give them to his friends in the figurine drawer.

The terror wight is acutely aware that the late release of The First Story pushes back the next one. Roy says he’s going to autograph covers of Littlelot and the Real Monster and give them to his friends in the figurine drawer.

Roy is a terror wight from my miniature figurine collection and the cover model for Littlelot and the Real Monster.

Roy is a terror wight from my miniature figurine collection and the cover model for Littlelot and the Real Monster.