Enterprise, Tennessee: The Town That Died

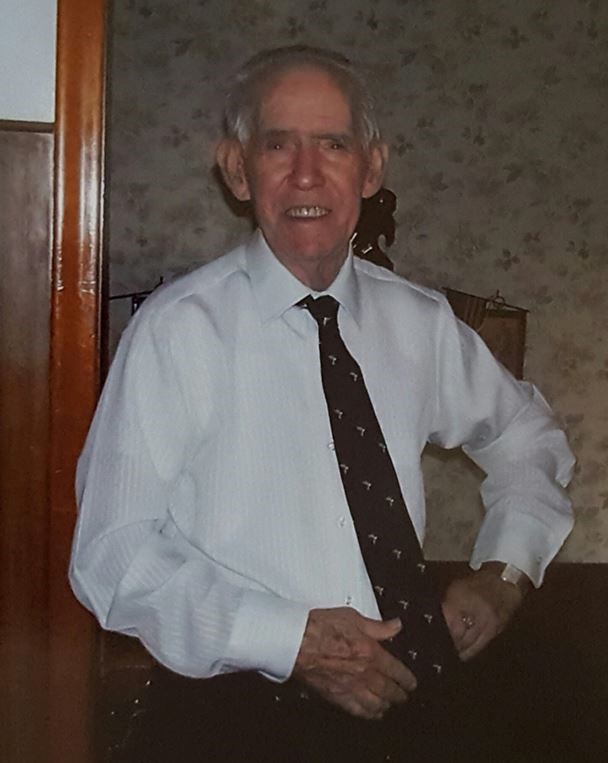

My great uncle John Wesley Potts, one of Ben Potts’s boys, was the family genealogist. To him the Potts family is thankful for much of the information we have concerning our family history. I have several photocopied pages of the family tree, which includes old photographs and a few stories. These last are in Uncle Wesley’s words, typed by his hand.

I’m fond of one story in particular. It reminds me of my favorite Dr. Seuss book, and like The Lorax, it remains pertinent. Furthermore, as it gives context to the childhood of our present subject, I think it appropriate at this point to transcribe the story of a town named Enterprise as told by John Wesley Potts.

Enterprise, Tennessee:

The Town That DiedEnterprise was a sawmill town on the banks of Lewis Branch. Around 1900, there were sawmills, stave and shingles. The town was aptly named because it was growing. It grew in size between 200 and 300 people.

The timber was plentiful. Virgin oaks, beach and hickory.

Grandpa Albert Jack Potts moved his family there in 1901 from Slayden, Tennessee.

Grandpa was a teamster. He owned matched pairs of horses. Him and the boys [Ben and his brothers] cut and snaked logs out of the wood to the roads. He got a dollar a day plus fifty cents for the horses.

In a few short years the timber was cut and the town slowly fell apart, much like the lumber towns of upper Michigan. He stayed in Houston County and bought a farm. He lived there until his death at 64, in 1929. Albert and Lou Ellen are buried in the McDonald Cemetery along with four of their children.

Pa would marvel at the way they lumber today.

My great grandfather, like many veterans, didn’t talk much about his wartime experience. His family has only his discharge paper and a few anecdotes.

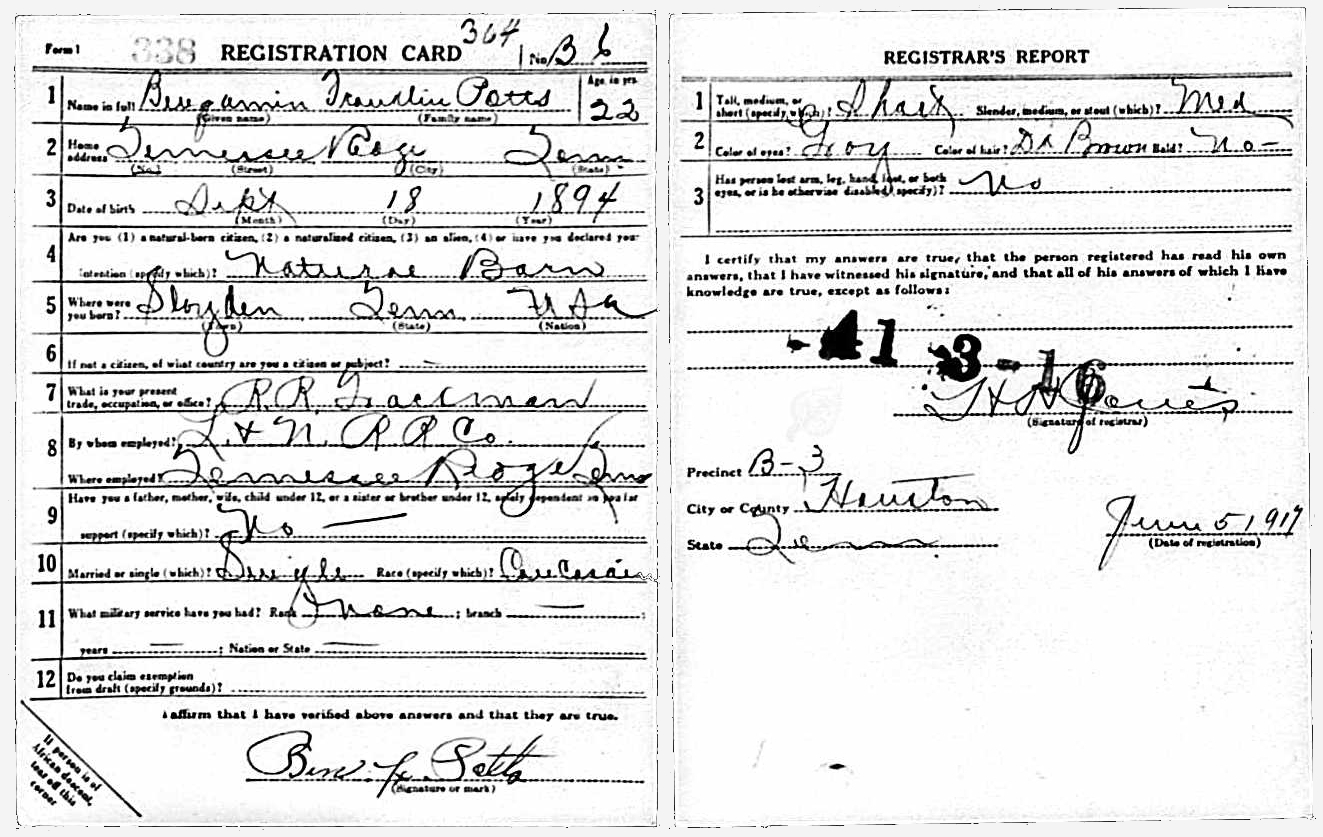

One hundred years later, I’ve discovered a few documents that bear his name. From draft registration to discharge, I’m following the paper trail of B. F. Potts’s journey to the battlefields of the Great War in France and back home again.

Previous articles:

“Well, Daddy, what did you think about France?”

“It’s a very muddy place.”

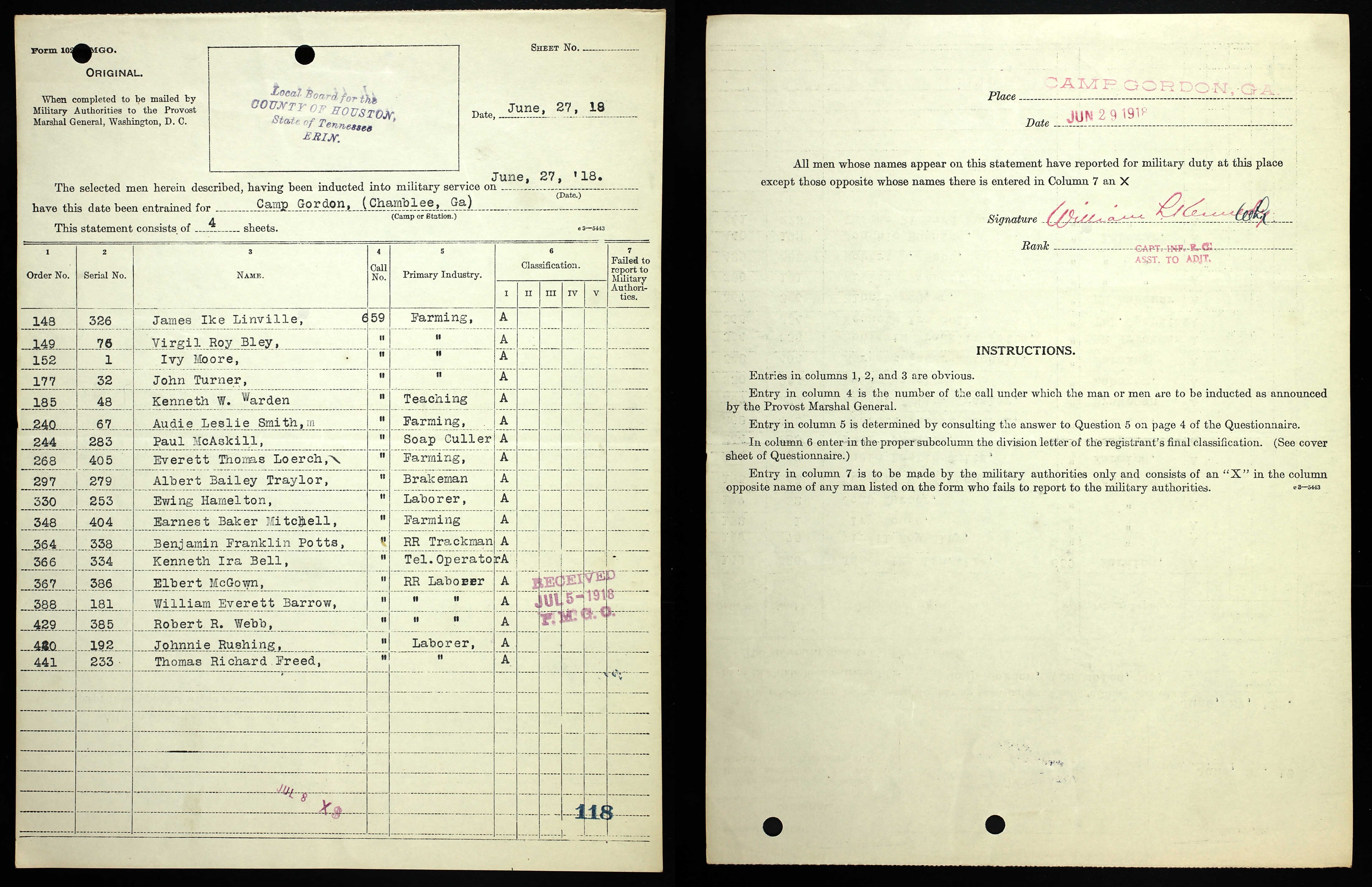

Benjamin Franklin Potts Registers for the Draft

As the Great War thundered across the fields of northern France, ten million American men, ages 21 to 30, signed their names to register to be drafted into military service.

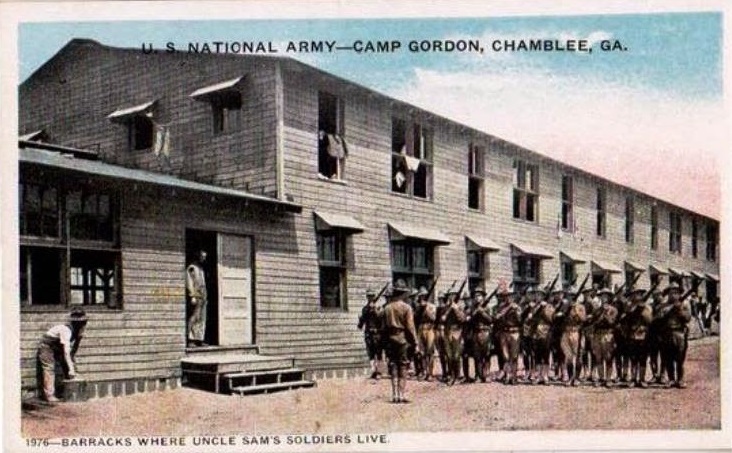

Military Induction and Entrainment

“I, Benjamin Franklin Potts, do solemnly swear to bear true allegiance to the United States of America, and to serve them honestly and faithfully, against all their enemies or opposers whatsoever…”

“If it moves, salute it. If it doesn’t move, paint it!”

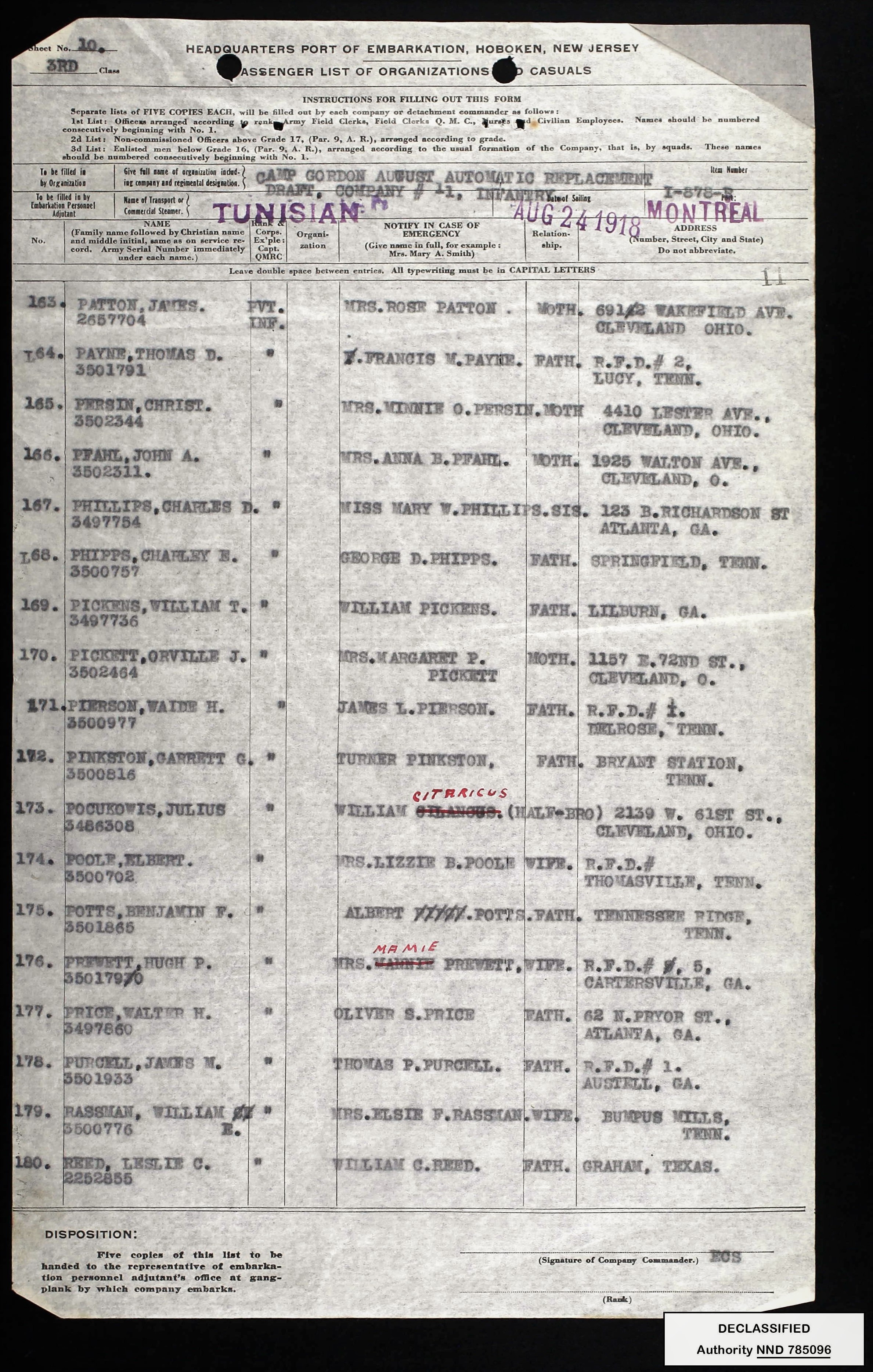

Embarkation, the Tunisian, and the Bridge of Ships

In his first ocean voyage, B. F. Potts crossed the submarine invested waters of the North Atlantic in a convoy of steamers escorted by a warship.

Next date:

September 7—Rendezvous with the 35th Infantry Division