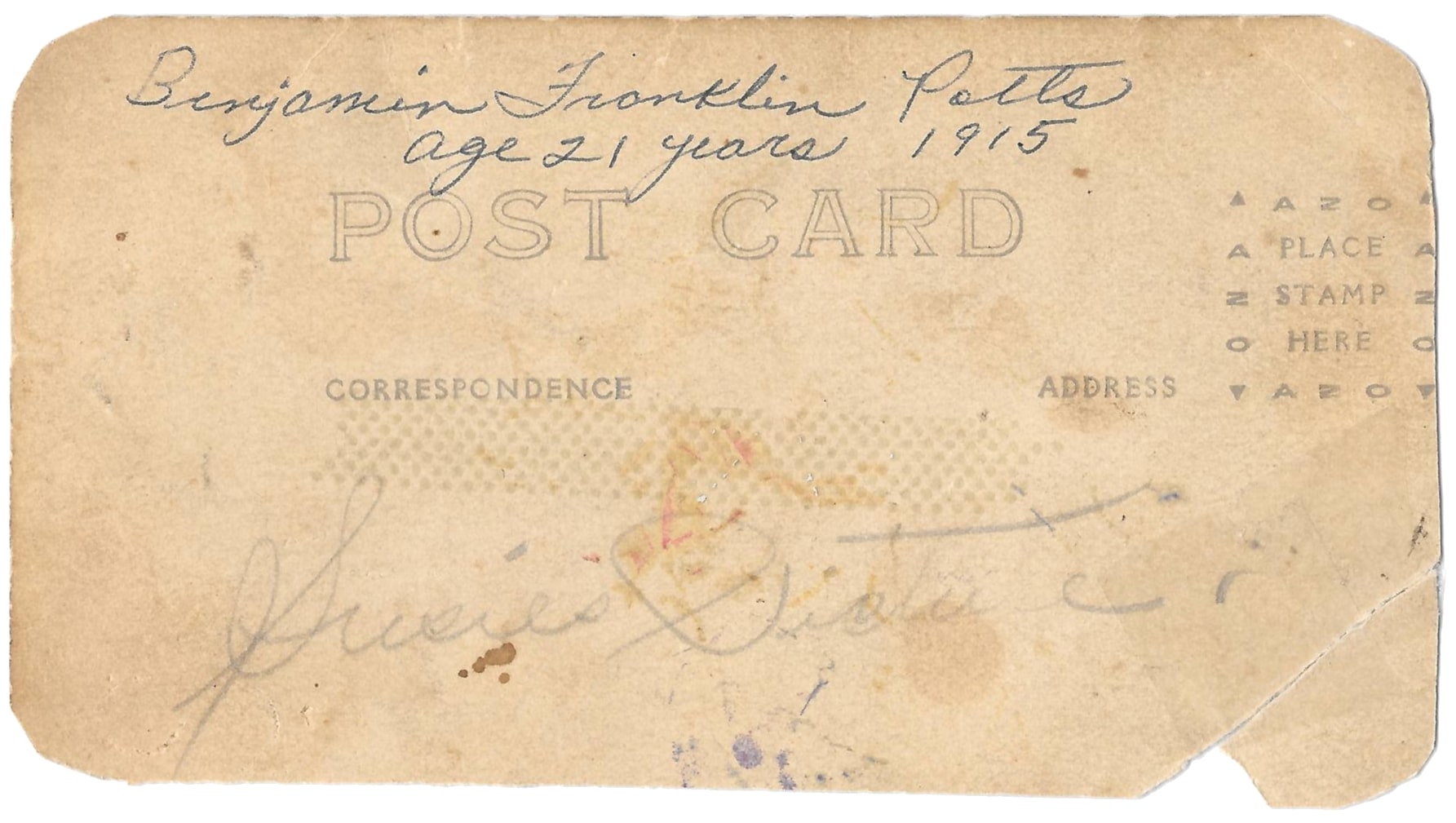

The photograph measures 2-3/4 by 5 inches. The image shows a young man, clean-shaven, dressed in wide-legged trousers, coat, and tie. A carnation adorns the left lapel. He wears a wristwatch. He sits, legs crossed, in a chair with a high back and one arm, made of wrapped rattan. The chair rests on a thin rug.

The chair’s single-armed design, according to my brief research, makes it a “ladies chair.” An open side allowed for wide skirts, and it sat low to the ground, so the lady didn’t have to bend so far to remove her shoes.

On the photo’s back, in blue ink, is written “Benjamin Franklin Potts age 21 years 1915.” My cousin Bruce says the writing is that of his father, my great uncle John Wesley Potts.

Also on the back, is printed “POST CARD” at the top, “CORRESPONDENCE” in the middle left, and “ADDRESS,” middle right, beside a stamp box. The stamp box is distinguished by the paper manufacturer’s name and four triangles in the corners, two up, two down.

We notice the sides have been trimmed, its corners cropped round. The lack of any message or postmark suggests the postcard was never used as such. At the bottom in a different hand is a penciled note: “Susie’s picture.”

At the beginning of the twentieth century, Kodak sparked a revolution in photography with its “Brownie” camera. While the camera and the photograph were invented in the previous century, protecting the photographic plate from light made photography a tedious process.

George Eastman bought the patent for roll film from inventor Peter Houston in 1889. Roll film was protected from light inside a paper wrapping. Eastman put roll film in a box camera and, in 1900, sold the first Brownies for one dollar each.

Kodak sold these cameras at a loss in order to sell the film at a profitable margin. In later decades, the strategy became known as the “razor and blades” model, after the patent ran out on King C. Gillette’s safety razor and competitors began offering the same product at a cheaper price.

The Brownie’s low cost and ease of use put cameras in the hands of many more people, including children. The amateur photographer was born.

The Private Mailing Card Act of Congress in 1898 permitted private industry to print postcards. Also in that year, a special rate for a postcard stamp was introduced. While a first class letter could be mailed for two cents, a postcard went for a single penny.

In 1907, the US Postal Service changed its regulation to allow a written message on the blank side of the postcard, which was until that time reserved for a stamp and delivery address. The regulation stipulated placement: stamp and address on the right, message on the left.

Kodak also made postcard photographic paper, on which a photograph could be developed from a negative. Kodak marketed these as “real photo” postcards. Though the photo was often smaller to reduce cost, the printed paper was 3-1/4 by 5-1/2 inches.

AZO was a Kodak brand manufacturer of photographic paper. The stamp box, like a watermark, can be used to date the paper. According to Robert Bogdan’s Real Photo Postcard Guide, the earliest known date for AZO’s paper with two triangles up and two down is October 1917.

The discrepancy in the date suggests this photograph was developed from the negative at a later time. The photograph or its original may well have been a family keepsake during Ben Potts’s eleven-month absence—perhaps kept by his younger sister, Susie.

A Very Muddy Place

WAR STORIES

An intimate account of a soldier’s experience in World War I, A Very Muddy Place takes us on a journey from a young man’s rural American hometown onto one of the great battlefields of France. We follow Private B. F. Potts with the 137th US Infantry Regiment through the first days of the Meuse-Argonne Offensive. We discover a personal story—touching, emotional, unforgettable.

In 1918, twenty-three-year-old Bennie Potts was drafted into the US Army to fight in the World War. He served with the American Expeditionary Force in France. At home after the war, he married and raised a family, and the war for his children and grandchildren became the anecdotes he told them.

A century later, a great grandson brings together his ancestor’s war stories and the historical record to follow Private Benjamin Franklin Potts from Tennessee to the Great War in France and back home again.

Available in hardcover, paperback, and e-book.

Disclosure: This page and linked pages contain affiliate links to Bookshop, Amazon, Apple, Barnes & Noble, and Kobo. As an affiliate of those retailers, Stephen earns a commission when you click through and make a purchase. Thank you for your support.