“Then [in war] there is a very great difficulty arising from the unreliability of all data. This means that all actions must necessarily be planned and carried out in a more or less uncertain light, which like a fog or moonshine, gives things a somewhat exaggerated and unnatural size and appearance.”—Clausewitz

Prussian General Carl von Clausewitz, in his On War (published 1832, posthumously), used “fog or moonshine” as a metaphor to demonstrate uncertainty in armed conflict. Military leaders and thinkers since have applied the metaphor to the chaos of the battlefield in particular, using the expression “the fog of war.”

The morning of September 26, 1918, the fog in the Aire Valley was figurative as well as literal. According to Kenamore, “It was possible to see 40 yards at times, but beyond that the fog shut in like a wall. A squad of men would be observed marching ahead, but a moment later they would entirely disappear, and there would be nothing to see but the opaque gray bank of fog. It was impossible to tell friend from foe 25 yards away.” (94-95)

Approaching Varennes, three kilometers north of the departure line sometime around 8 a.m., Third Battalion, 137th Infantry Regiment, had by now outdistanced the artillery’s useful range. The division’s 60th Field Artillery Brigade was ordered forward.

However, portions of the 60th’s planned route, Route Nationale No. 46, had been destroyed by the retreating enemy. The guns had to be hauled through the mud of the now conquered No Man’s Land, some by double teams of horses (a team is six horses), some by platoons of men. Only one battery, which counts four guns, made itself heard that afternoon. The commanders didn’t know it yet, but the 35th Division would be virtually without artillery support well into the next day.

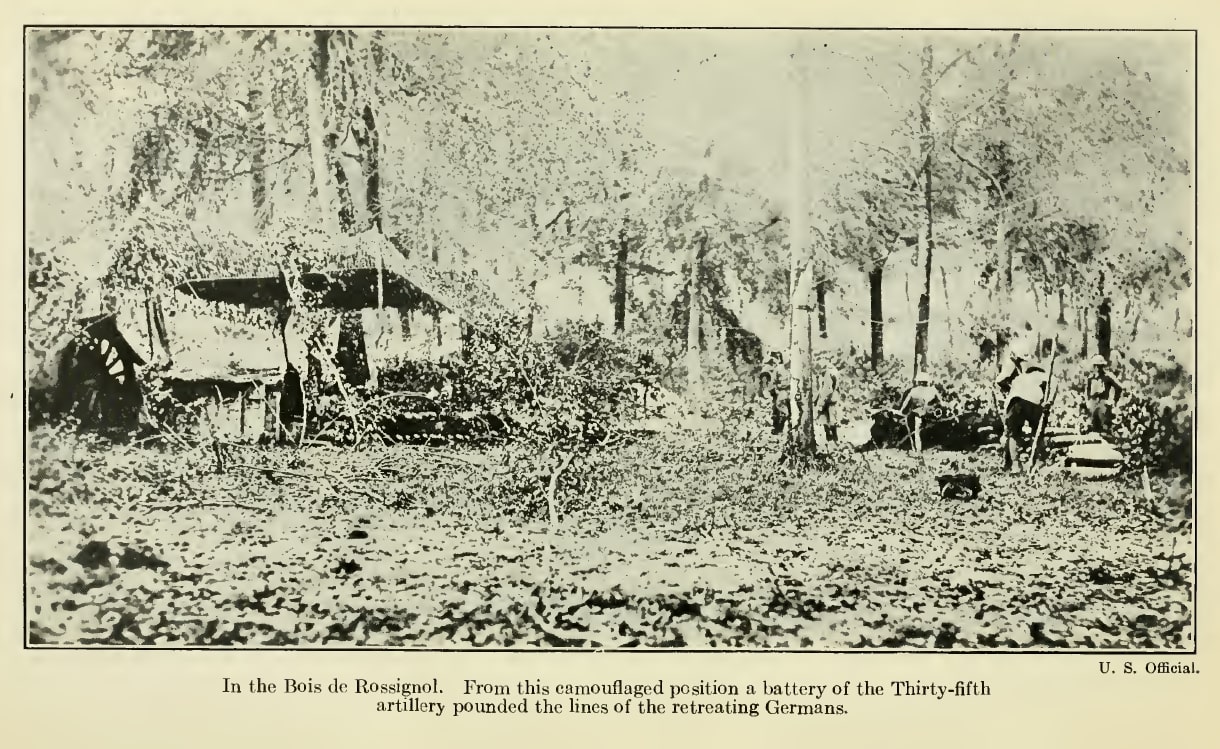

A battery of the 129th Field Artillery Regiment in Rossignol Wood, the afternoon, September 26, 1918 (Hoyt 75)

A battery of the 129th Field Artillery Regiment in Rossignol Wood, the afternoon, September 26, 1918 (Hoyt 75)

To make matters worse, across the division boundary on the 137th’s left, the 28th Division met stiff resistance in the Argonne Forest. Their advance was slow. What’s more, their own artillery, having departed later, was blocked in traffic on the Route Nationale. This left the 137th’s left flank open to counterattack by ground troops and artillery fire from the Argonne heights. With troops of the 28th out of range and no artillery to threaten them, enemy machine guns in the sector had nothing to do but fire on the 137th.

The German Maschinengewehr 08 fired 500 rounds a minute at an effective range of 2,000 meters. That’s two squares on the map. Also notice the contour lines showing higher elevations west of the Aire. From there, German 77mm guns fired down on the 137th.

The German Maschinengewehr 08 fired 500 rounds a minute at an effective range of 2,000 meters. That’s two squares on the map. Also notice the contour lines showing higher elevations west of the Aire. From there, German 77mm guns fired down on the 137th.

“The leading battalion of [the] 137th Infantry had been checked by machine gun and flank artillery fire on the outskirts of the village [Varennes]. Every gray-walled little house, even to the gaunt remains of the town church, seemed to have within a machine gun.” (Hoyt 74)

Here, the regimental commander, Colonel Clad Hamilton, whose headquarters detachment traveled with the battalion, ordered the men to dig in to protect themselves from incoming fire. While waiting for his Second Battalion to come up, Hamilton tried to contact brigade headquarters to get artillery support. Everyone hoped the fog would clear.

Kenamore devotes a six-page chapter to battlefield communication, its devices, and its failure that day (135-140). Signal flags, flash lamps, and “heliographs” (a system using mirrors) were useless in the fog. Carrier pigeons were confused by the fog, smoke, and artillery fire. The telephone, depending on a wire connection, was impractical. A front line signal platoon had got working a wireless set in a shell hole. But because divisional headquarters failed to install their own set, they could only listen to the time from the Eiffel Tower.

Kenamore also mentions “T. P. S.,” which stands for “télégraphie par le sol.” The ground telegraph was invented in 1917 by Frenchman Paul Boucherot. “This is a system of telephoning without wires, using the ground as a conducting medium. It is most successful for distances up to a few miles.” (136-137) T. P. S. seems to have been also ineffective.

“Runners were the only means left, and they had almost no landmarks to guide them through the fog and smoke.” (137)

We have previously assumed that Private Potts was selected to be a runner. In the present situation, a commander, having exhausted other more immediate means of communication at his disposal, might resort to this means.

Scrawling in a notepad, the commander tears the sheet, folds it, and thrusts it into the runner’s hands.

“Potts, take this message to brigade. Tell them we need artillery now. Go!”

Off he goes. Message secured in a pocket, rifle in hand, chin strap fastened tight, Private Potts dodges machine-gun fire and artillery shells, as he moves down the slopes south of Varennes. Brigade Headquarters’ last known position, which it had occupied since five days before the battle, was at Mamelon Blanc, a hilltop five kilometers away on the other side of Vauquois Hill.

While the 137th was stalled before Varennes, the support regiment, the 139th, moved up around to the east to continue the advance. Farther to the right, the 138th took Cheppy around 9 a.m. Without artillery support, the 344th Tank Battalion, of the 1st Tank Brigade, came to their aid. The tank brigade commander came up on foot to see how the tanks were performing. Thirty-two year old Lieutenant Colonel George Patton was hit by a machine gunner’s bullet. He didn’t sit comfortably for some weeks thereafter.

Gasping for breath, Private Potts slows to a walk as he approaches a group of men and horses dragging a big gun through mud.

“Pull, pull, pull!” says one man at the front of a line of men on a rope. The gun’s wheels turn out of a depression, gaining several feet.

Potts calls out, “Hey, I’m looking for 69th Brigade Headquarters.”

The lead man steps forward, removing round spectacles to wipe sweat from his brow. His straight nose forms a perfect triangle. “There’s a road a mile that way,” he says throwing an arm in the gun’s direction. “They’ll be somewhere along there.”

“Thanks, and good luck!” says Potts, as he breaks into a trot through the mud.

Kenamore: “The failure of liaison and all mechanical means of communication cost the lives of many brave men in the front lines in the course of the battle… Runners would be dispatched. If they were not killed or wounded en route, they probably would find the agile brigade headquarters had moved from the shell hole in which it had last been seen, and there would be no one there to tell where it was gone. The search for the headquarters would continue while the battery or machine gun nest would continue to take its toll of American lives.” (137)

If the runner found headquarters and managed the return journey, the response he carried would have informed the regimental commander of the situation. In any case, by 10:30 a.m., the 137th’s Second Battalion came in line with our Third Battalion. As the fog cleared, flanking fire became more intense. If troops are taking fire, they may as well be taking ground, too. The assault on Varennes was accomplished without artillery support.

Haterius: “Beyond Varennes was situated what was known as the ‘Grotto,’ a wooded hill surmounted by an ancient chapel and shrine. Numerous machine-guns were pivoted here, and a battery of ‘seventy-sevens’ [German 77mm artillery guns] made it a ‘strong point’ of no mean calibre. The Grotto was taken by noon of the 26th by the Second and Third Battalions.” (146)

By 4:00 p.m., the 35th Division halted along a line five kilometers from the morning’s parallel of departure. Though, due to the confusion of the day, the units were well mixed, their general positions are recorded as follows: having passed ahead of the 137th, the 139th dug in on the line one kilometer south of Charpentry; east of Buanthe Creek, the 138th was one kilometer north of Véry; the 140th to its south; and the 137th north of Varennes.

As night falls on the Aire Valley, Private B. F. Potts is overwhelmed by a profound sense of fatigue. He hasn’t eaten since yesterday. Congestion on the roads and continued shelling prevent food from coming up so far. His canteen is empty. Retreating Germans are known to poison water points behind them. In the dark, he would like to lie down and sleep, despite falling artillery, but he is denied even that. Fog of war be damned, there is still work to do.

“The sleepless runners pounded away on the eternal task of trying to find in the darkness an unknown Colonel and deliver to him a message from a Brigadier General who would assuredly have moved before the runner returned.” (Kenamore 141)

My great grandfather, like many veterans, didn’t talk much about his wartime experience. His family has only his discharge paper and a few anecdotes.

One hundred years later, I’ve discovered a few documents that bear his name. From draft registration to discharge, I’m following the paper trail of B. F. Potts’s journey to the battlefields of the Great War in France and back home again.

Previous articles:

“Well, Daddy, what did you think about France?”

“It’s a very muddy place.”

Benjamin Franklin Potts Registers for the Draft

As the Great War thundered across the fields of northern France, ten million American men, ages 21 to 30, signed their names to register to be drafted into military service.

Military Induction and Entrainment

“I, Benjamin Franklin Potts, do solemnly swear to bear true allegiance to the United States of America, and to serve them honestly and faithfully, against all their enemies or opposers whatsoever…”

“If it moves, salute it. If it doesn’t move, paint it!”

Embarkation, the Tunisian, and the Bridge of Ships

In his first ocean voyage, B. F. Potts crossed the submarine invested waters of the North Atlantic in a convoy of steamers escorted by a warship.

Enterprise, Tennessee: The Town That Died

Grandpa owned matched pairs of horses. Him and the boys [Ben and his brothers] cut and snaked logs out of the wood to the roads. He got a dollar a day plus fifty cents for the horses.

Rendezvous with the 35th Infantry Division

“Some of the guys disobeyed orders, went into the town, broke into a bakery, and stole all the bread and baked goods…”

The battle of Saint-Mihiel (September 12-15) would be Pershing’s first operation as army commander. He assigned the 35th to the strategic reserve, whose purpose is to replace a weakened unit or to fill any gap in the line created by the enemy.

“Private Potts, how tall are you?”

The soldier, looking into a button of the captain’s coat, says, “Five foot three, sir.” The wide brim raises.

On the front now, the 35th was in range of artillery fire, and enemy planes made nighttime bombing raids over the countryside.

Planning the Meuse-Argonne Offensive

On the left, the 137th would take the “V of Vauquois,” a formidable network of trenches, zig-zagging from the hill’s west flank to the village of Boureuilles, a mile away.

The gun jumps, the earth shudders, a shock wave shatters the air and accompanies a roar that bursts between the ears. Powder fumes permeate the air. Explosions count seconds across unending darkness.

…up until 7:40 a.m. when the rolling barrage ceased, we can follow Private Potts’s movement across the battlefield.

Next date:

September 27—Night Attack

On War by General Carl von Clausewitz, Miss A. M. E. Maguire, translator, London: William Clowes and Sons 1909, 13-14.