September 28, 1918, the sun rose, unseen. A cold, drizzling rain fell from a close sky. On the slopes of the hollow north of Baulny, men of the 137th and 139th regiments lay, soaking wet, chilled to the bone. Sleep was impossible with the cold, the damp, and the night’s steady shelling.

A hundred meters northwest of the hollow rose a gentle hill topped with trees, called Montrebeau (sounds like mantra-bow) Wood, which in French means “showing beauty.” As the sky lightened from its darkest black, the shelling increased, and a wave of gray-clad soldiers broke from the wood, rushing down the hill. The enemy skirmish line was repulsed with machine-gun and rifle fire. Thus began the 35th Infantry Division’s third day of battle.

The day’s orders were to advance through Montrebeau Wood. The attack would begin at 6:30 a.m. Today, the infantrymen would have support from their artillery, though it would never be as heavy as the first morning.

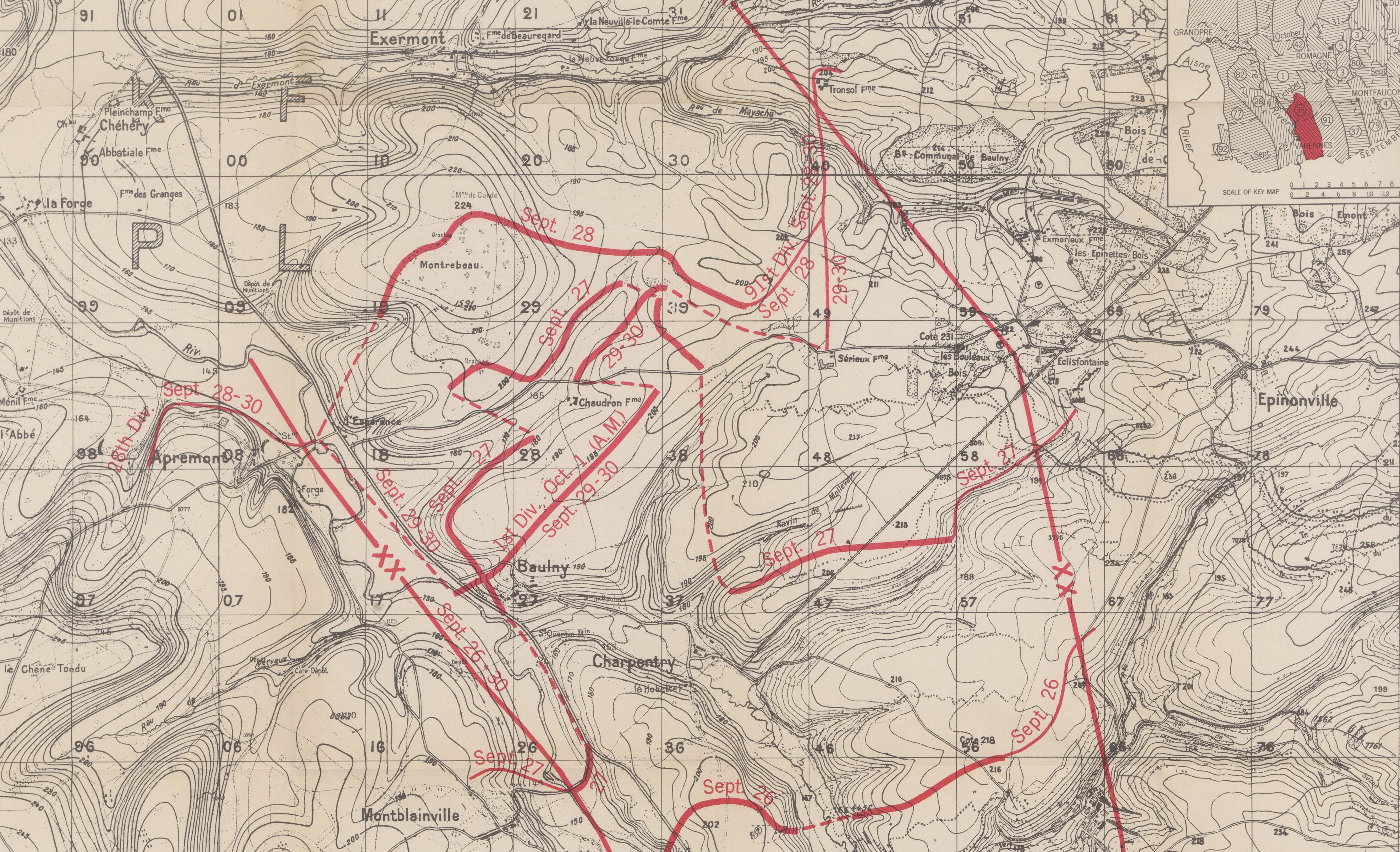

Map section, September 28, 35th Division, Grange le Comte Sector, Meuse-Argonne, American Battle Monuments Commision 1937

Map section, September 28, 35th Division, Grange le Comte Sector, Meuse-Argonne, American Battle Monuments Commision 1937

“It was under the lowering sky of a cold, dark fall day. All the glory was gone out of the war, with the glitter and pageantry of the first day’s successes, but they went ahead. They were not the dashing lads who went over the top two days before, but they were veterans of battle, hardened soldiers who no longer had any delusions about a soldier’s life.” (Kenamore 178)

They advanced through strafing machine-gun fire from the woods ahead. Haterius quotes a French officer, who observed the action: “Those d— Americans have no sense; they know not when to stop; they go against machine-gun fire barehanded.” (146) By morning’s end, the intermingled 137th and 139th regiments gained 500 meters and dug in before Montrebeau Wood.

“Montrebeau Wood was a thick tangle of trees and underbrush about the size of a square kilometer [more than half a square mile]. It contains, I should say on a guess, 240 acres. There were many lines and systems of barbed wire entanglements thrown through it. The Americans had to cut paths through this wire. The Germans had trails already made, which they knew, but it was difficult and dangerous for our men to find them.” (Kenamore 179)

Through the woods and German machine-gun nests and sniper fire, the men fought in the afternoon. By dark, this ensemble, the remains of the 137th and 139th Regiments, held the line on the other side of Montrebeau Wood.

On the division’s right, the 140th lead the attack. Beginning an hour earlier than the left, the orders to the regimental commander were “to take his regiment forward with all speed to protect the flank of the troops on his left [the 137th and 139th].” (Kenamore 179). The regiment pushed through relentless artillery fire, being rather more exposed as they advanced over the northern, enemy-facing slopes.

At day’s end, they dug in just north of the “little hollow,” which had been occupied by their division comrades on the left the previous night. They did, however, manage to rejoin the line.

Tonight, the 35th Division defended a more or less cohesive front on the north edge of Montrebeau Wood, from its western slopes to 500 meters northwest of Sérieux Farm, where the 35th connected to the 91st Division on its right. Furthermore, on its left, the 28th Division made great advances in the day, taking Apremont, near the western division boundary. There was, however, a gap in the 35th’s sector between it and the 28th.

Encounter at Creek’s Edge

“When I asked him [Grandpa Ben] if he killed anyone, this is what he told me: They had just been in action and his best friend had been killed that day and he was very upset. As he left the area he was walking through the woods and came up behind a German soldier eating his lunch as he was sitting on a rock next to a stream. Grandpa said he tried to turn to go in a different direction away from the soldier but stepped on a stick or leaves and made noise, which alerted the German to his presence. The German soldier reached for his rifle so Grandpa said he had no choice and shot the soldier. Then Grandpa said to me something I have never forgotten: ‘He fell forward into the creek and I never did see that boy again.’”—Bruce Potts

My great grandfather, like many veterans, didn’t talk much about his wartime experience. His family has only his discharge paper and a few anecdotes.

One hundred years later, I’ve discovered a few documents that bear his name. From draft registration to discharge, I’m following the paper trail of B. F. Potts’s journey to the battlefields of the Great War in France and back home again.

Previous articles:

“Well, Daddy, what did you think about France?”

“It’s a very muddy place.”

Benjamin Franklin Potts Registers for the Draft

As the Great War thundered across the fields of northern France, ten million American men, ages 21 to 30, signed their names to register to be drafted into military service.

Military Induction and Entrainment

“I, Benjamin Franklin Potts, do solemnly swear to bear true allegiance to the United States of America, and to serve them honestly and faithfully, against all their enemies or opposers whatsoever…”

“If it moves, salute it. If it doesn’t move, paint it!”

Embarkation, the Tunisian, and the Bridge of Ships

In his first ocean voyage, B. F. Potts crossed the submarine invested waters of the North Atlantic in a convoy of steamers escorted by a warship.

Enterprise, Tennessee: The Town That Died

Grandpa owned matched pairs of horses. Him and the boys [Ben and his brothers] cut and snaked logs out of the wood to the roads. He got a dollar a day plus fifty cents for the horses.

Rendezvous with the 35th Infantry Division

“Some of the guys disobeyed orders, went into the town, broke into a bakery, and stole all the bread and baked goods…”

The battle of Saint-Mihiel (September 12-15) would be Pershing’s first operation as army commander. He assigned the 35th to the strategic reserve, whose purpose is to replace a weakened unit or to fill any gap in the line created by the enemy.

“Private Potts, how tall are you?”

The soldier, looking into a button of the captain’s coat, says, “Five foot three, sir.” The wide brim raises.

On the front now, the 35th was in range of artillery fire, and enemy planes made nighttime bombing raids over the countryside.

Planning the Meuse-Argonne Offensive

On the left, the 137th would take the “V of Vauquois,” a formidable network of trenches, zig-zagging from the hill’s west flank to the village of Boureuilles, a mile away.

The gun jumps, the earth shudders, a shock wave shatters the air and accompanies a roar that bursts between the ears. Powder fumes permeate the air. Explosions count seconds across unending darkness.

…up until 7:40 a.m. when the rolling barrage ceased, we can follow Private Potts’s movement across the battlefield.

Scrawling in a notepad, the commander tears the sheet, folds it, and thrusts it into the runner’s hands.

“Potts, take this message to brigade. Tell them we need artillery now. Go!”

“Let him lie in an artillery shower all night, if you must. But do not disturb a soldier’s sleep, sir, with your orders that change from one minute to the next!”

Next date:

September 28—Encounter at Creek’s Edge

September 29—Charge to Exermont