Military Induction and Entrainment

“I, Benjamin Franklin Potts, do solemnly swear that I will support the constitution of the United States.”

The words feel like strangers in the mouth, being, at the same time, repeated after a man in uniform and of such moral import.

The American flag on his right, the Tennessee Tristar, left, the army officer stands before a group of young men. They are farmers, teachers, laborers, and railroad men. All dressed in their best clothes, they’re aligned in loose ranks. A small suitcase or a simple bag, containing a change of clothes and a shaving kit, sits on the floor to each man’s left. Their right hands are raised, palms out.

The officer continues: “I, state your name…”

“I, Benjamin Franklin Potts, do solemnly swear to bear true allegiance to the United States of America, and to serve them honestly and faithfully, against all their enemies or opposers whatsoever, and to observe and obey the orders of the President of the United States of America, and the orders of the officers appointed over me.”

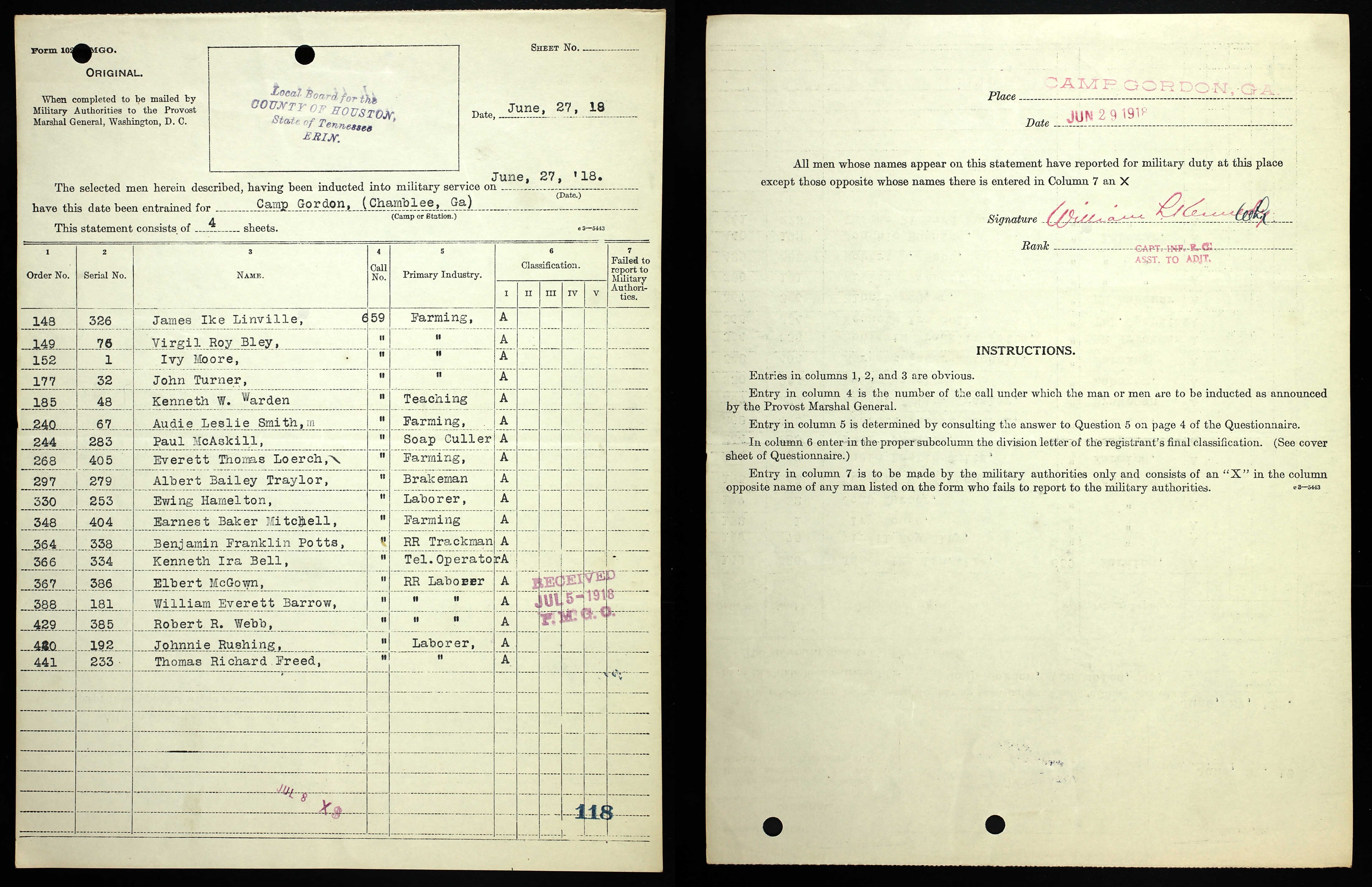

June 27, 1918, one hundred years ago today, my great grandfather spoke these words, right hand raised, at the Houston County Court House in Erin, Tennessee, and so became a private in the U.S. Army.

The two oaths, taken by all commissioned and noncommissioned officers and privates, were defined by the First United States Congress in 1789. The oath for officers changed over the years, but the oaths for enlisted men stayed the same until the mid-20th century.

Following the brief ceremony, Private Potts was escorted onto a train with several dozen other draftees. On boarding, each man was given two box lunches, supplied by the Red Cross Society of Erin, that would be his dinner and supper. The train pulled out for Camp Gordon in Chamblee, Georgia, where they would undergo six weeks of military training.

Three months from that day, my great grandfather would be fighting in France.

Form 1029, Provost Marshal General Office, showing Benjamin Franklin Potts (12th entry) was inducted and entrained for Camp Gordon June 27, 1918, and arrived two days later

Two of Ben’s three brothers were also drafted for the war. Nine months prior, Roy Albert, two years Ben’s senior, took the same train to Camp Gordon. The youngest, Clyde Brake, would leave for Camp Wadsworth near Spartanburg, South Carolina, in September 1918. Only the eldest, William Rufus, was excluded from the draft, being married with two young children at the time.

My great grandfather, like many veterans, didn’t talk much about his wartime experience. His family has only his discharge paper and a few anecdotes.

One hundred years later, I’ve discovered a few documents that bear his name. From draft registration to discharge, I’m following the paper trail of B. F. Potts’ journey to the battlefields of the Great War in France and back home again.

Previous articles:

“Well, Daddy, what did you think about France?”

“It’s a very muddy place.”

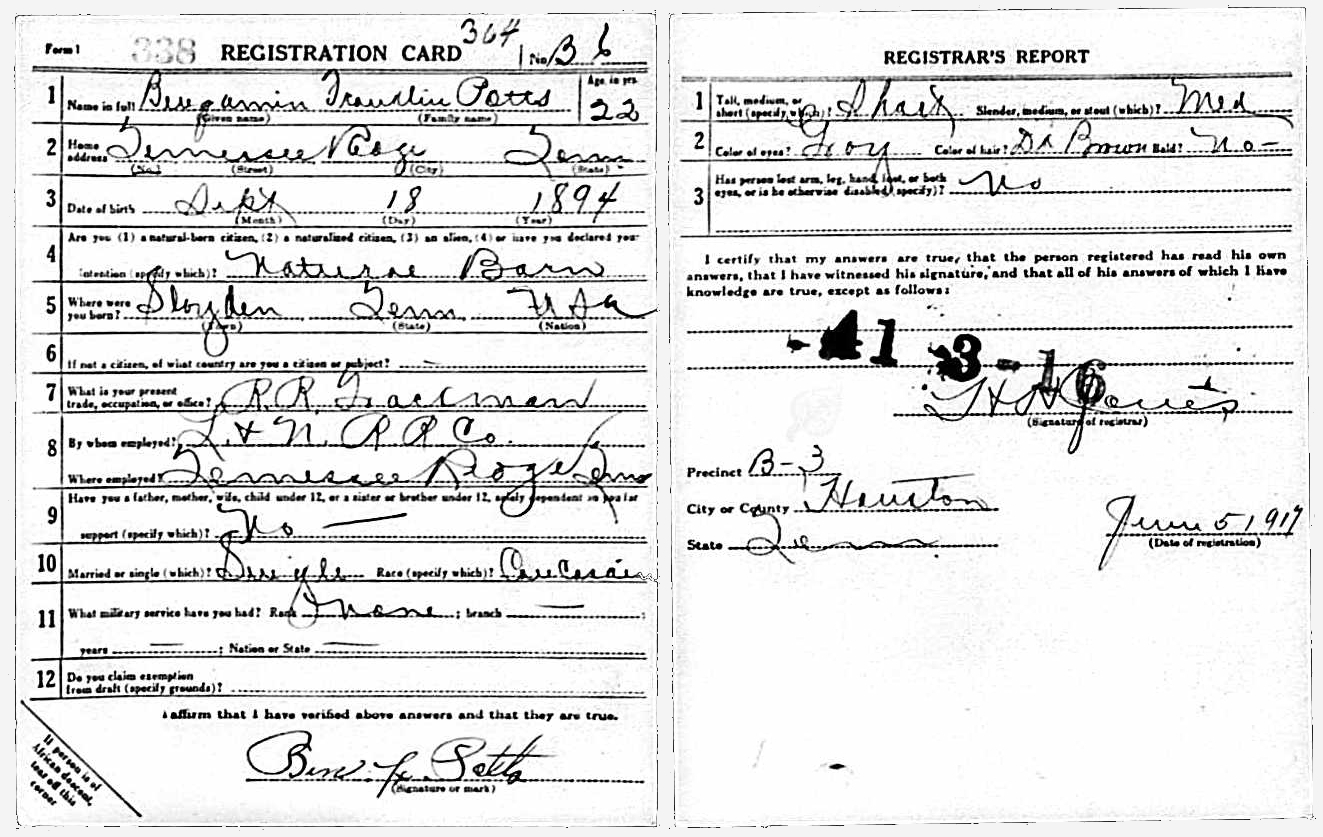

Benjamin Franklin Potts Registers for the Draft

As the Great War thundered across the fields of northern France, ten million American men, ages 21 to 30, signed their names to register to be drafted into military service.

Next article: