All blossoms fallen

All blossoms fallen

Like samurai in battle;

Souls to heaven rise

All blossoms fallen

Like samurai in battle;

Souls to heaven rise

The First Story of Littlelot is an Arthurian legend with knights and damsels and other action figures.

The First Story of Littlelot is an Arthurian legend with knights and damsels and other action figures.

In his game of make-believe, a boy must make a choice—break his oath to the king or break the heart of the woman who gave him the most meaningful gift.

Preface

The valiant knight in shining armor rides a resplendent steed on dangerous adventures. He surmounts overwhelming obstacles, rights terrible wrongs, and rescues the damsel in distress.

That’s what I want to be when I grow up!

Alas, I was born centuries too late. As were you, Young Reader, if such might be your own grown-up ambition. Left to us in our times are stories of those chivalric heroes, models that we may yet apply to our modern lives.

The quintessential tale of noble knights is that of King Arthur and the knights of the Round Table as told by Sir Thomas Malory in Le Morte d’Arthur. Reputedly a knight himself, Malory compiled his fifteenth-century rendering from various sources, among them, the Vulgate Cycle, the Prose Tristan, and the Stanzaic Morte Arthur. Each of these drew on earlier works, including Geoffrey of Monmouth’s History of the Kings of Britain and a collection of stories by the French troubadour Chrétien de Troyes. In turn, Malory’s work inspired a profusion of novels, narrative poetry, films, and other forms, collectively known as “Arthurian legend.”

The First Story of Littlelot recounts the adventure of the most renowned of all the Round Table knights, Lancelot, and his rescue of Gwenevere, drawn from Book VII of Le Morte d’Arthur. My own retelling differs from Malory’s in length as well as in certain details.

Stephen Wendell

December 14, 2016

Paris, France

The First Story of

Littlelot

Full-Color Illustrated Edition

In his game of make-believe, a boy must make a choice—break his oath to the king or break the heart of the woman who gave him the most meaningful gift.

An Arthurian legend with knights and damsels and other action figures.

The frontispiece and six chapter illustrations by celebrated artists Arthur Rackham, N. C. Wyeth, Thomas Moran, and Herbert James Draper bring Littlelot’s Arthurian adventure to life in this beautiful paperback book.

Available in paperback and e-book.

The First Story of

Littlelot

An Arthurian legend with knights and damsels and other action figures.

In his game of make-believe, a boy must make a choice—break his oath to the king or break the heart of the woman who gave him the most meaningful gift.

Available in paperback and e-book.

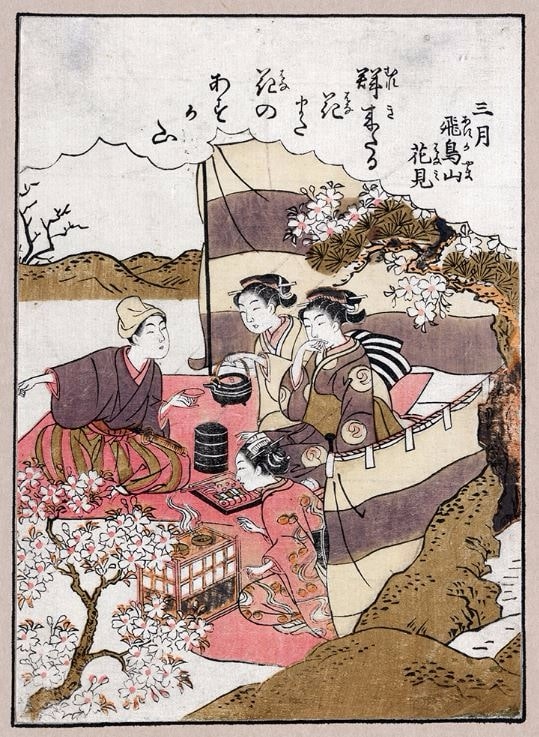

The way opens between hedge rows. Birds chitter within. One enters by a narrow lane, and the world blooms into rosy hues. A soft breeze through branches carries pink petals, fluttering. Well dressed men and women, checkered blankets spread beneath them, clink glasses. Laughing children roll in lush green grass. Tiny birds flit from branch to branch, tree to tree, twittering the news: “Springtime, springtime! Springtime is here!”

I walked into a cherry orchard at the Parc de Sceaux. All the trees were in full bloom, all the people were there to see them, and everyone brought a picnic.

A young man, wearing dark pants and white button-up shirt, set up a camera on a tripod. Its lens, as long as my forearm, extended toward hanging blossoms, dazzling in the sunlight. The hollow pop of a cork leaving a Champagne bottle turned heads and made a girl giggle.

A young man, wearing dark pants and white button-up shirt, set up a camera on a tripod. Its lens, as long as my forearm, extended toward hanging blossoms, dazzling in the sunlight. The hollow pop of a cork leaving a Champagne bottle turned heads and made a girl giggle.

“Is there a party?” I asked, my American accent coming through the French.

“Hanami,” he said with a Japanese accent, “ancient Japanese custom, big spring celebration.”

We chatted for a few minutes while he lined up a shot with the camera. I took a few photos as well and made a note to look up this custom when I got home. This is what I found:

In eighth-century Japan, neighboring Chinese culture was considered more sophisticated. Such was its influence that the Japanese capital, Nara, was modeled after its Chinese counterpart, including numerous plum trees imported from China. In the region, plum trees bloom in late February and mark the end of winter.

Emperor Saga in the early ninth century is credited as the first to throw a party in a blooming orchard. Thus hanami, “flower viewing” in Japanese, began among the elite of the imperial court.

Due to a rebellion in China, that country’s exports to Japan halted. The intercultural rupture is marked by the 894 abolition of Japan’s official delegations to China, which required an arduous crossing of the Sea of Japan. Reduced influence from the mainland allowed an independent Japanese culture to flourish, and the native cherry tree gained in popularity over the plum tree. Blooming at the end of March, cherry blossoms mark the arrival of spring.

History measures the popularity of plum and cherry blossoms by the number of mentions each receives in various ancient texts, such as chronicles, diaries, and poetry, including waka and haiku. So many mentions for plums in this century versus only this many for cherries. The next couple centuries see an increase in cherry mentions and a decrease in plums. Vote for your favorite thing in writing.

Hanami remained a practice of the elite until the eighteenth century. His people suffering from poverty and hunger, Shogun Tokugawa Yoshimune invited local subjects into a private cherry orchard to share in the springtime festival, which included a feast as well as cherry blossoms. The event was well received. The shogun then ordered the planting of cherry trees along rivers and lanes and encouraged the people to participate in the annual event.

Today, hanami is as popular as ever in Japan, and the custom has spread around the world. In France, the trees blossom mid-April, when some 200 Japanese cherry trees attract locals and tourists to two orchards in the Parc de Sceaux, south of Paris.

If you want to see the spectacle, it’s happening this week!

Stephen Wendell lives near the Parc de Sceaux, where he goes for a daily run. He is the author of the Littlelot series of children’s books and The Way to Vict’ry, a book of three haiku inspired by Sun Tzu, Matthieu Ricard, and a magpie flight instructor.

View of the north cherry tree orchard, west of the Grand Canal, Parc de Sceaux. If you miss the pink ones, the white cherry blossoms, in the south orchard farther down the lane, peak a couple weeks later.

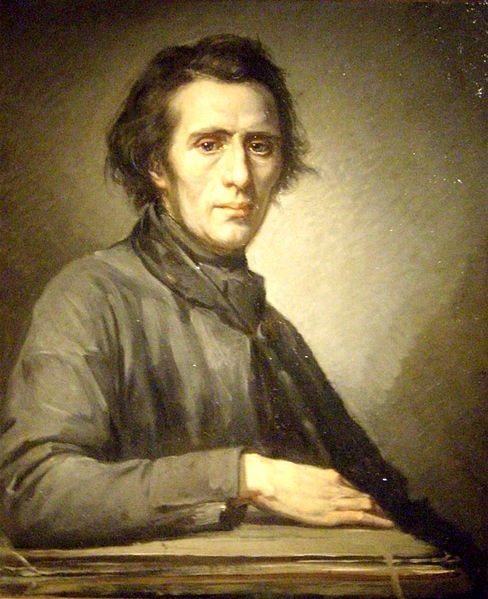

“You don’t mean to tell me that this young man made those drawings by himself!” said Mouchel.

The elder Millet defended his affirmation, saying he watched his son draw them. He had brought Jean-François to see this Cherbourg artist who was also a tutor. They showed him two drawings the boy had made, hoping Mouchel would take him on as pupil.

The younger Millet insisted on his sole authorship, and Mouchel was eventually convinced.

“Well, then,” he said to the father, “all I can say is, you will be damned for having kept him so long at the plough, for your boy has the making of a great painter in him.” (Cartwright 32)

Thus, Jean-François Millet went to study painting in Cherbourg. Of his first tutors, history records little. Alfred Sensier devotes a few pages to these two characters in his Millet biography. Those pages, including footnotes added by the editor Paul Mantz, may well have saved the names of Bon Dumoucel, called “Mouchel,” and Lucien-Théophile Langlois from history’s oubliette. Though my research is far from exhaustive, Sensier’s work is the source of every other reference to them I’ve so far found.

Sensier describes Mouchel as a curious character. A self-taught artist, he followed the neoclassical School of Jacques-Louis David. He began many large canvases but didn’t always finish them. On request of local clergy, he painted alter.jpgeces, which he then donated to the church.

Mouchel taught at his home-studio in a small valley on the edge of town, where he lived with his wife. He worked a garden beside a mill and had a pet pig whose language he understood and could speak. Sensier, less bold, writes, “pretended to understand” (emphasis mine).

As Millet’s tutor, he recognized genius in the young man and gave him free rein: “Draw what you like; choose anything of mine that you like to copy; follow your own inclination, and above all go to the Museum.” (Cartwright 33)

It was at the Thomas Henry Museum where a messenger found Jean-François to inform him of his father’s illness.

Months later, Millet returned to Cherbourg under another tutor. Théophile Langlois de Chévreville was a trained artist, student of Antoine-Jean Gros, also neoclassical. During his own studies, Langlois had traveled to Greece and Italy, a fact he made sure everyone knew. He was considered as Cherbourg’s best painter. Some years later, he would become a drawing professor at the town college.

Like Mouchel, seeing that he didn’t have much to teach the young man, Langlois gave his student much the same treatment as his predecessor. “Go to the Museum,” was a common refrain.

After less than a year, Langlois penned a letter to the Cherbourg town council to make Millet’s case. In the letter, he suggested that the town provide the promising artist with a scholarship to study in Paris. So confident was he in Millet’s talent, he dared to predict the future:

“Allow me, gentlemen, for once, to lift the veil of the future, and to promise you a place in the memory of mankind, if you help in this manner to endow our country with another great man.”

In January of 1837 with a Cherbourg scholarship of 600 francs, Jean-François Millet bid farewell to his mother and grandmother at Gruchy and rode by carriage to Paris.

Quoted dialog from Jean-François Millet, His Life and Letters by Julia Cartwright (London: Swan Sonnenshein & Co., 1896).

Biographical information from La vie et l’oeuvre de Jean-François Millet by Alfred Sensier (Paris: A. Quantin, 1881).